By AUSTIN FULLER

By AUSTIN FULLER

GLENWOOD, Fla. (AP) – Benjamin Smith swung a machete as he cut his way through the brush looking for the graves of his father and grandparents.

The Glenwood African American Cemetery was established in 1885 and is the only one of about 75 Volusia County cemeteries that is completely abandoned, according to Volusia County spokesman Dave Byron. Some gravestones are covered with leaves and vines. Others are cracked or missing.

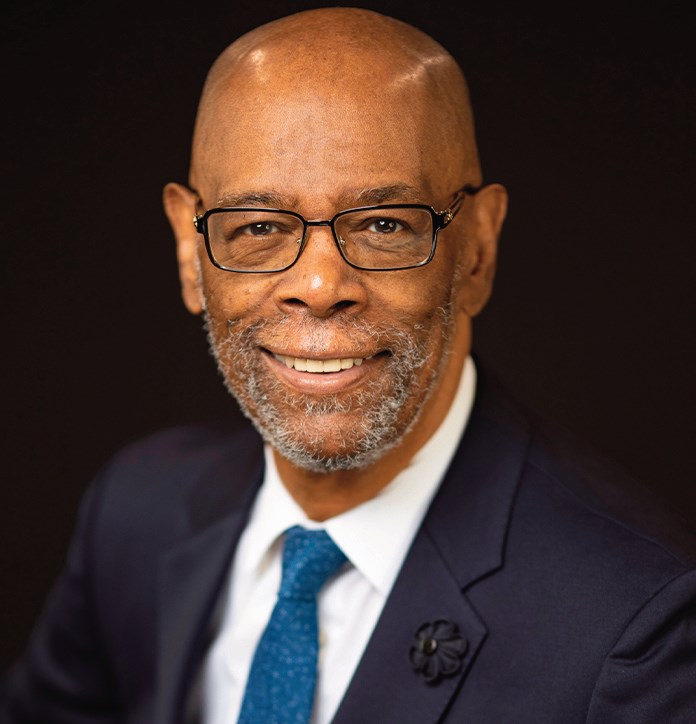

Smith, a 70-year-old retired pastor with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, said he’s been seeking help for years to clean up the cemetery in Glenwood off of a dirt road called Church Street.

“I’ve been trying to get help for the last at least four years,” he said.

The graveyard, which includes the graves of World War I veterans, is indistinguishable from the woods that surround the final resting places of those buried there.

Smith said he remembers going to the cemetery for funerals while growing up. “It was taken care of,” he said.

His grandmother Mary Etta Smith, who was born in Glenwood in 1901 and later worked as a nanny, was buried there in 1988. His grandfather Benjamin Fred Smith, whose job was contracting labor for fruit harvesting, was born in 1901 and died in 1937. His dad was also buried in the cemetery after he died at age 65 around 1986. He was a mechanic and heavy equipment operator born in Glenwood before moving to DeLand.

Glenwood once was home to a large percentage of African-Americans following the railroad’s construction in the 1880s to around 1936, according to a January 1986 article in the DeLand Sun News and provided by the West Volusia Historical Society. Family members of a person buried in the cemetery about three months before the 1986 article told the newspaper a sawmill had drawn residents there to work and harvest wood.

In 2012, the county’s historic preservation officer documented 32 intact grave markers, Byron said, but many more unmarked graves exist. The last burial at the cemetery took place in 1999, he said, but it has been neglected for around 20 years.

The graveyard is listed as one of the Volusia County Historic Preservation Board’s most endangered historic properties, Byron said.

Nancy Epps, chairwoman of the board, said a cemetery is a sacred place and it’s important for properties like this to be maintained and protected. But funds are tight in government, she said. She suggested a student volunteer effort to clean it up.

Many of the county’s approximately 75 cemeteries have some form of neglect, but the Glenwood cemetery is the only one completely abandoned, according to Byron.

Volusia County property records show the land is owned by the county, but Byron explained that the association behind the cemetery no longer exists and county ownership means it’s not owned by anyone else.

“The county would be happy to support a volunteer effort to preserve and improve this cemetery,” Byron wrote in an email.

Retired pastor Smith said he is willing to lead an effort to clean up the cemetery but he needs volunteers and knows it’s a task that cannot be accomplished quickly.

“Right now, it’s pretty hard to go in there and clear it up with any equipment,” he said. “So it would have to be done by hand with a lot of manual labor.”

He was previously able to get help from his cousins to clear around their family’s graves.

One DeLand resident who could be willing to join the volunteer effort is Paul Gercak, who is concerned about the graves of veterans in the cemetery.

“Their final resting place is a disgrace,” Gercak said.

Florida has thousands of abandoned graveyards, according to the Florida Department of State’s Division of Historical Resources website.

“The most successful efforts to rehabilitate and care for abandoned and neglected cemeteries depend on community organization and volunteer effort,” the department’s website states.

Karen Ryder, an archivist and curator for the West Volusia Historical Society, sees restoring the graveyard as important to remembering the community.

“Otherwise, it’s lost. It’s lost forever,” Ryder said. “That piece of history is gone. There’s something about ourselves and our identity, history gives us our identity, and there’s something of our identity, something of who we are that is not known and every piece is significant.”

No Comment