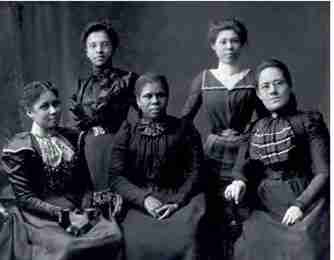

PHOTO COURTESY OF KUT

By ISHEKA N. HARRISON

MIAMI – On Friday, Aug. 25, the eve of Women’s Equality Day, The New Florida Majority (NewFM) hosted a video conference with over 70 participants entitled, “The True History of Black Women in the Women’s Suffrage Movement.”

The conference focused on having an honest conversation about how black women were marginalized during the Women’s Suffrage Movement, despite being some of its most engaged proponents.

It featured presentations from Dr. Ameenah Shakir, an assistant professor of history at Florida A&M University (FAMU) and Jasmen Rogers, an organizer in Miami-Dade and Broward counties. It was moderated by Renee’ Mowatt, NewFM’s communications coordinator.

After introducing NewFM as a “statewide social justice organization working to increase the political power of Florida’s black and brown communities,” Mowatt allowed the speakers to share their expertise.

Shakir began her presentation with a history of black women’s involvement in the women’s suffrage movement.

“African American women played a significant role trying to secure suffrage, in the particular passage of the 19th amendment in 1920,” Shakir said. “For African American women this effort to secure suffrage from the very beginning was an effort to really compete and to really support the larger black freedom struggle and in particular to fight the dual oppressions of both racism and sexism in America.”

Naming iconic historical figures like Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells and others, Shakir said historically black women had to stand up against viewing suffrage through “a white female lens,” specifically highlighting the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848.

“White female suffragists to a large extent (were) advocating an agenda that at the time supported notions of what we later would understand as white supremacy. … Black women suffragists from the outset rejected these ideas … Institutionally and organizationally there were these racialized differences about how black bodies were going to be considered in America,” Shakir said.

According to Shakir, these differences led to an explosion of organizing including the upstart of many black women’s clubs that fought to address issues that specifically affected them.

“They’re fighting for not only voting rights, but they in particular see the franchise or the vote as a way to secure women’s empowerment, in particular black women’s empowerment,” Shakir said.

She also noted though the passage of the 19th Amendment began securing access for white women into a lot of other places in American society, it was not the same for black women.

After sharing more history, Shakir turned the conversation over to Rogers, who echoed her colleague’s sentiments.

Citing Truth’s famous “Ain’t I A Woman” poem as one of the earliest assertions of black feminism, Rogers highlighted the stark divide between white and black women suffragists.

“White women and white people are talking about the right to vote … but they’re not including black people in this conversation” Rogers said. “There were folks that even when she presented this in 1851 in Ohio that said if we let Truth talk and if we address her claims as a black woman then we’re going to be associated with abolitionists and niggers so there was this divide that was very obviously, ‘We want women to vote, but we don’t want black people to vote.’”

Rogers also highlighted the fact that despite white women suffragists calling black women friends, they still treated them as inferior.

“Susan B. Anthony believed in segregated marches and tried to get Ida B. Wells and her black folks to march at the back of a women’s march because their idea was if we have black women marching alongside white southern women, white southern women would get upset and would not believe in the cause of women’s suffrage.”

However, Rogers said Wells took her place in the march where she pleased anyway.

“What we see throughout history is this perpetual white feminism that prides whiteness over our connection to the feminist movement in really demeaning ways and dehumanizing ways for black women,” Rogers said. “Folks like Susan B. Anthony, past and present, have claimed solidarity and claimed friendship and claimed all these things in public and in private, but then when it came down to actually practicing that intersectionality, they were just really, really weak on it and it was very non-existent.”

Rogers further said white women’s silence on many issues concerning blacks historically prolonged the mistreatment and killing of blacks.

She shared some of her personal experiences with ‘white feminism’ and asked that white women today sacrifice some of their white privilege to help black and brown communities. She also offered suggestions on how they could do so.

At the end of Shakir and Roger’s presentations, Mowatt opened the conference for audience questions and announced NewFM would partner with the Miami Worker’s Center and other organizations to present the Florida March for Black Women on Sep. 30.

For more information about this and other events, visit www.newfloridamajority.org.

No Comment