CHARLESTON, S.C. (AP) – Sometimes, standing before his audience, Chris Singleton likes to tell the story of the father and son walking the beach after a hurricane has destroyed their home. Strewn across the sand are hundreds of starfish, washed up by the storm and on the verge of death. The father, preoccupied with the extent of his material loss, loses patience.

“Son, this is futile! There are so many, you can’t save them all.” The son examines the starfish in his hand and turns to his father.

“But I can save this one,” he says, and tosses it into the sea.

And Singleton thinks to himself during his inspirational talks, maybe he can help someone, too. Of all the people gathered in the room, surely one or two are in pain, surely one or two need more than just a good word.

So Singleton asks everyone to stand, to find “someone who doesn’t look like you,” to give that person a hug and declare “I love you.” He knows it might be awkward for many, but the statistical odds are in his favor. Nearly 5 percent of U.S. adults are coping with depression; around 11 percent are dealing with forms of anxiety, according to government statistics.

He was one of them. On June 17, 2015, when he was 18 years old, he received a phone call informing him about a shooting at Emanuel AME Church, where his mother, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, was an assistant pastor involved in Wednesday night Bible study.

His father, who struggled with alcoholism, was not around much, so it was Chris who was forced to grow up fast and care for his two younger siblings. He took his responsibility very seriously.

“I was pretending to be Superman,” he said.

He was appearing in the media; he was balancing his own educational and athletic goals with his dedication to family; he was pretending he had it all under control.

A year and half later, his father died. At his funeral, the dam holding back his emotions burst, and Singleton, now aware of his own vulnerability, was renewed.

“I stopped being the person no one could relate to,” he said.

He has returned to Mother Emanuel on occasion, but stepping inside the building tends to fill him with dread, and he avoids the basement altogether. That’s where a young white supremacist determined to start a race war was welcomed by the Bible study group that Wednesday night. That’s where the bullets went flying. That’s where his mother and eight others died six years ago.

Once, though, he ventured reluctantly into that space, afraid of what his emotions might do to him. But it was oddly helpful, he said. And, like many moments of discomfort in his life, it brought to mind a favorite passage from Proverbs 24: “If you faint in the day of adversity, your strength is small.”

There he was in the place that once filled with blood. There he was in the place where Sharonda Coleman-Singleton was taken from the world.

“It was sort of a relief addressing the thing I was super anxious about,” he said.

And it is sort of a relief for him to talk about it a little during his appearances before audiences. Every time, without fail, he invokes his mother’s name.

Singleton, who will be 25 on July 5, is busy on the speaker’s circuit. He spends perhaps 100 days each year on the road and another 100 on local and regional stages. The COVID-19 pandemic forced him online for a spell, but now in-person events are ramping up again.

REACHING THE YOUNG

Over the past few years, he has accumulated his anecdotes and honed his delivery. He has around 20 different 10-minute segments that he can mix and match, emphasizing a certain message over others: overcoming adversity, the importance of love and unity, faith and forgiveness, racial reconciliation. Mostly, he tells stories, peppering them with facts and stats.

He is equally comfortable addressing elders in church pews and young people on the baseball diamond. He has avoided sharing his story with children. Understanding the violence and racism at the heart of it requires a certain maturity, he said.

So, to reach this younger audience, he wrote a children’s book in 2020 called “Different,” about a child from Nigeria who settles in Charleston, gets teased at school but ultimately is accepted. The message: together we are stronger.

Singleton had no intention to write another children’s book, but “Different” sold more than 18,000 copies in about a year’s time, suggesting that perhaps his is an important voice for young people to hear.

In March, a boutique Californiabased publisher, Bushel & Peck Books, released “Your Life Matters,” which is about the importance of teaching Black history and features a variety of prominent figures such as Maya Angelou,

Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King Jr., Aretha Franklin, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Mary McLeod Bethune and George Washington Carver. Sales are off to a great start, he said.

HARD WORK

Those books soon will be used at home in Hanahan. Singleton’s wife Mariana is pregnant with their second child, due in September. He will be called Caden. Their older boy, Chris Jr., or C.J. for short, is 3. Everything Singleton does is for his family, he said.

He does a lot.

As director of community outreach for the Charleston RiverDogs, he manages relationships with schools, nonprofits, corporations and others. He oversees charity matches, scholarship distribution, reading and ESOL initiatives for the Latino community, private mascot appearances (sometimes he dons the suit himself), baseball clinics and summer camps for area students.

He is loyal to the RiverDogs organization because the RiverDogs organization is loyal to him, he said. Management accepts _ and supports _ Singleton’s career as a public speaker. He gets adequate time to travel and deliver his message.

“I love baseball,” he said.

He grew up playing sports. As a student at Goose Creek High School, he excelled at basketball and baseball. The latter ultimately won his heart, but he persisted with the former through high school. His basketball coach, Blake Hall, quickly noticed his player’s talents.

“He has an infectious personality,” Hall said. “He was very personable. Has his mother’s smile, which will brighten the room. He has an energy about him, a presence about him.” And he was a hard worker.

Hall credits Singleton – and other highly motivated student achievers _ with helping him become a better coach.

“As an educator and coach, a lot of times you learn more from your kids than the kids learn from you,” he said.

Hall became an influential person in Singleton’s life, someone in whom the young man could trust. For here was someone who genuinely cared, who used the term “son” freely, who insisted on honesty and respect.

The coach stays in touch and admires what Singleton has become.

“He’s going to be a leader and an example … in his community for the rest of his life,” Hall said.

FEARLESS UP THERE

Singleton attended Charleston Southern University, where he advanced his baseball career and strengthened his faith. He was there when the call came about the church shooting.

In 2017, he was drafted by the Chicago Cubs to play in the minor leagues. But a conflict grew as he strived to find some balance between a career in sports and a spiritual calling to share his messages of hope. He promised himself he would find a way to honor his mother, and public speaking seemed to be the best way to do so.

He was released by the Cubs in 2019 and embraced by audiences hungry to understand how this young man could endure such pain and turn it into fuel for his soul, how he could channel a mighty love.

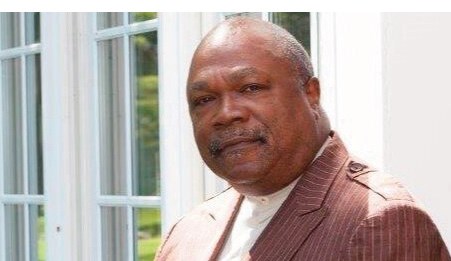

Maurice Johnson is a longtime family friend and among the people Singleton trusts most. “Uncle Reese” is not surprised by Singleton’s success. He saw it coming.

“His mom, Sharonda, was a speech therapist,” Johnson said. “She always instilled this level of confidence in these young people, and gave them their voice at such a young age.” No wonder Chris is such a skilled public speaker.

“He’s almost fearless up there.” No wonder he found the words to address his pain.

No wonder he found the words to forgive.

Johnson recalled visits to the Singleton home and the manner in which Sharonda spoke to her children.

“(She) held no punches,” Johnson said. “She spoke to them like they were mature individuals. I was watching the conversation. I listened to her talk to them and give them direction, how she was conscious of the way they spoke, it was almost as if she was preparing them early on to be leaders, to be different than everybody else. She was intentional about how her kids were going to be, (and) how God was present in their lives. You can see it. It’s evident.”

And then Chris Singleton, just 18 at the time, suddenly was primary caregiver of his younger siblings. Suddenly, he was making big decisions. Suddenly, he was an adult.

“He was trying to be everything to his brother and sister, and he did an amazing job,” Johnson said.

Yet he had the maturity to understand that he could not do all of this alone, so he invited others to help, to guide, to support him.

“It looks like he has it all together,” Johnson said. “Part of that is knowing when he needs help.”

Singleton is sure that he is following a path he alone has not forged. He has learned from his grieving that in pain there is purpose. He has accepted that some forms of pain never disappear, that it should not be ignored or suppressed or belittled. It’s OK to hurt. The challenge is figuring out how to channel anguish in productive ways.

“We go through things to hopefully pull someone else through,” he said. “That’s what I do with my life now, just try to pull people out of that storm.”

No Comment