Associated Press

FAYETTEVILLE, N.C. — A condemned killer’s trial was so tainted by the racially influenced decisions of prosecutors that he should be removed from death row and serve a life sentence, a judge ruled Friday in a precedent-setting North Carolina decision.

Superior Court Judge Greg Weeks’ decision in the case of Marcus Robinson came in the first test of a 2009 state law that allows death row prisoners and capital murder defendants to challenge their sentences or prosecutors’ decisions with statistics and other evidence beyond documents or witness testimony.

Only Kentucky has a law like North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act which says the prisoner’s sentence is reduced to life in prison without parole if the claim is successful.

“The Racial Justice Act represents a landmark reform in capital sentencing in our state,” Weeks said in Fayetteville on Friday. “There are those who disagree with this but it is the law.”

Race played a “persistent, pervasive and distorting role” in jury selection and couldn’t be explained other than that “prosecutors have intentionally discriminated” against Robinson and other capital defendants statewide, Weeks said.

Prosecutors eliminated black jurors more than twice as often as white jurors, according to a study by two Michigan State University law professors Weeks said he found highly reliable.

Robinson’s case is the first of more than 150 pending cases to get an evidentiary hearing before a judge. Prosecutors said they planned to challenge Weeks’ decision but District Attorney Billy West declined further comment.

Weeks ruled race was a factor in prosecution decisions to reject potential black jurors before the murder trial of Robinson, a black man convicted of killing a white teenager in 1991. The jury that convicted Robinson had nine whites, two blacks and one American Indian.

Robinson and co-defendant Roderick Williams Jr. were convicted of murdering 17-year-old Erik Tornblom after the teen gave his killers a ride from a Fayetteville convenience store. Tornblom was forced to drive to a field, where he was shot with a sawed-off shotgun.

Robinson came close to death in January 2007 but a judge blocked his scheduled execution. Williams is serving a life sentence.

Nearly a dozen members of Tornblom’s family left the courtroom without commenting. Robinson’s mother, Shirley Burns, said she would advocate for the law, which a new Republican majority in the state’s General Assembly is trying to eliminate.

Central to Robinson’s case was the Michigan State University study. It reported that of almost 160 people on North Carolina’s death row 31 had all-white juries and 38 had only one person of color.

Study co-author and Michigan State professor Barbara O’Brien told a North Carolina legislative panel in March that the review of more than 7,400 potential capital jurors couldn’t find anything other than race to explain why potential black jurors were rejected by prosecutors more than twice as often as whites.

Robinson’s defense attorney James Ferguson of Charlotte told Weeks, who decided the case without a jury, that the study showed race was a significant factor in almost every one of North Carolina’s prosecutorial districts as prosecutors decided to challenge and eliminate black jurors.

“This case is important because it provides an opportunity for all of us to recognize that race far too often has been a significant factor in jury selection in capital cases,” Ferguson said when the hearing opened in January.

Union County prosecutor Jonathan Perry, who helped the Cumberland County District Attorney’s Office argue the case against Robinson, said the study was untrustworthy because it was based on a too limited sample of death penalty cases to provide meaningful results. The study also failed to detect numerous nonracial reasons for which a person might be struck from a jury, Perry said.

The Republican-led Legislature tried to repeal the Racial Justice Act earlier this year but lawmakers failed to override a veto by Gov. Beverly Perdue, a Democrat.

In 1998, Kentucky became the first state to enact a similar law. But the American Bar Association said in a report it was unclear exactly how often it has been used except for during the 2003 trial of an African-American man accused of kidnapping and killing his ex-girlfriend, who was white. In that case, the defendant’s lawyers used the Kentucky Racial Justice Act during jury selection to include questions that would address the issue of racial discrimination.

Associated Press writer Janet Cappiello contributed to this report from Louisville, Ky.

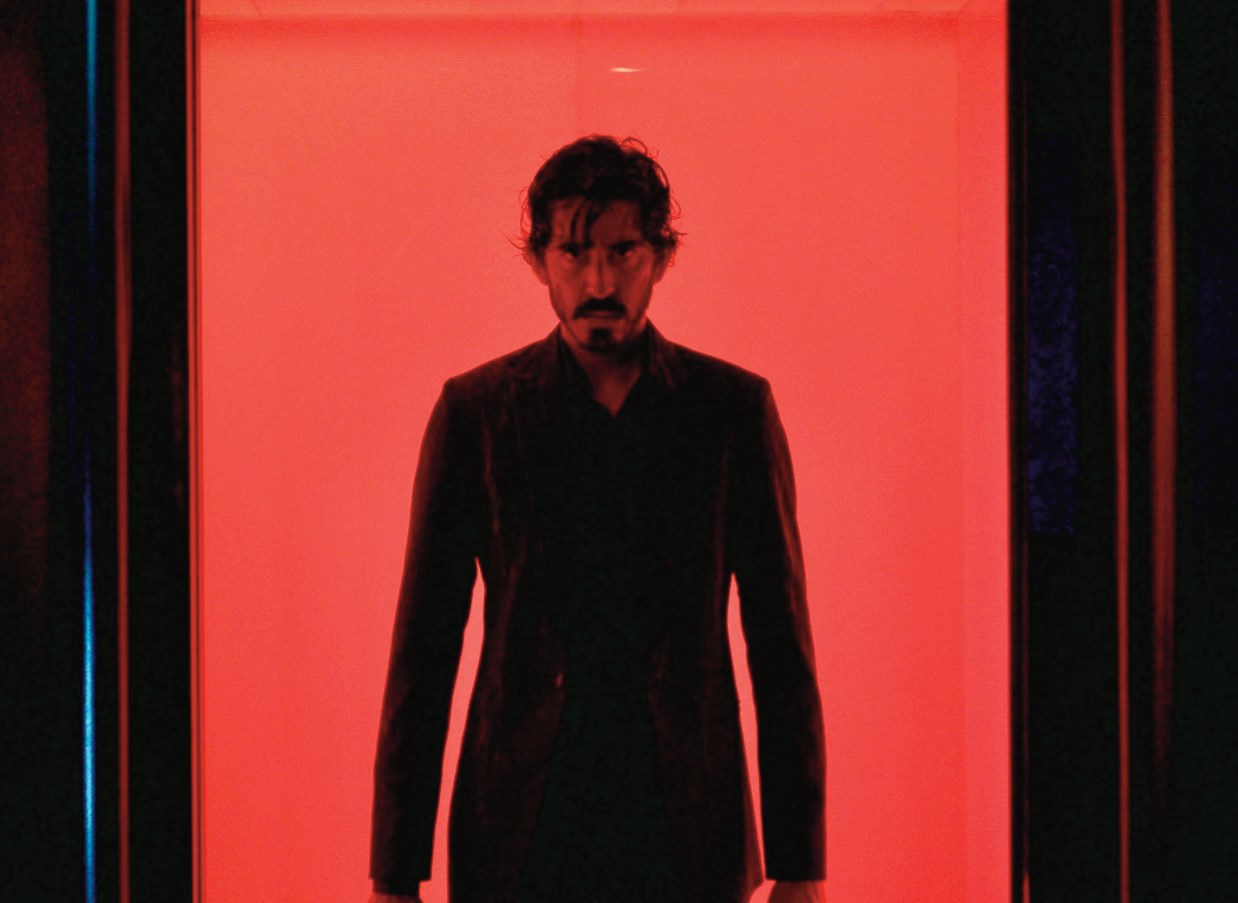

Photo: Greg Weeks

No Comment