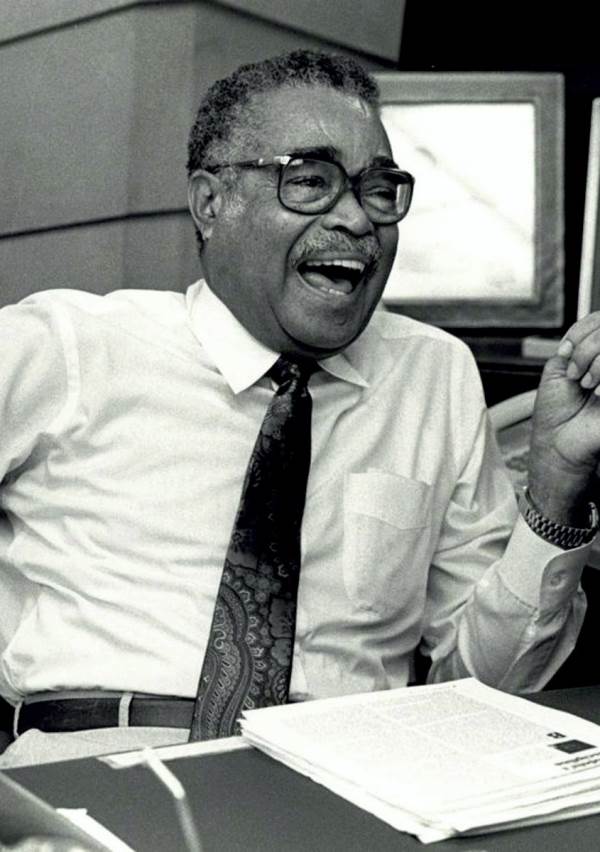

PHOTO COURTESY OF MIAMITIMESONLINE.COM

MIAMI – When icons talk, it’s best to listen. It’s one of the reasons Garth Coleridge Reeves Sr.’s prophetic declaration in 2017 that he would become a centurion is so memorable. As with many things in his epic life, Reeves was right. He died on Monday, Nov. 25 at the age of 100.

“People make too much of my age, but I’m gon’ make 100. I’ve pressed God a lot about it,” Reeves said. The publisher emeritus of The Miami Times was being honored with Garth C. Reeves Way in Miami’s Historic Overtown at the time.

“I see a lot of my friends and I’m glad they came out to wish your old boy luck because 98 is nothing to play with,” Reeves added. But luck had nothing to do with the exemplary legacy he left. His use of strategy, organizing and business prowess as an avid media maker, civil rights activist and community icon cemented his place in history.

One of the most notable ways Reeves helped his people was by amplifying their voices. Through the newspaper founded by his father, Reeves called out racism, fought oppression and held corrupt leaders accountable. He ascended to legendary status in the process.

“He was not afraid and he was not intimidated. He was dedicated to uplifting the race and he was not afraid to throw rocks … to get the power structure’s attention to the difficulties and the inequalities of the black community. He dedicated his life to that,” Dorothy Jenkins Fields, the founder of the Black Archives, History and Research Foundation of South Florida, told the Miami Herald.

THE EARLY YEARS THAT SHAPED HIM

Born February 12, 1919 to Rachel Cooper and Henry Ethelbert Sigismund Reeves, Garth C. Reeves emigrated to Overtown, Miami (then known as Colored Town) with his family when he was just four months old. In, 1923, when he was just four-years-old, his father founded The Miami Times.

Reeves grew up working on the printing side of the newspaper. He attended Booker T. Washington High School, the only secondary school for black students at the time – and graduated in 1936.

He went on to study printing at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU). After graduating in 1940, he risked his life fighting for his country in the U.S. Army during World War II.

A VOICE FOR THE VOICELESS

Reeves returned home from the war only to find that black people were still being treated as inhumane, second class citizens. His anger at America’s hypocrisy spurred his passionate activism.

He used his family’s newspaper – the oldest, largest and most notable black-owned publication in the Southeast – to highlight the black struggle.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Reeves put action behind his words. He was instrumental in desegregating Miami’s beaches and golf clubs, taking the latter fight all the way to the Supreme Court, which paved the way to desegregate golf clubs across the country.

Despite risking retaliation by police and white supremacy groups, Reeves was fearless. In an interview with History Miami Museum, he demonstrated just how much.

“I remember talking to Martin (Luther King Jr.) a few times and I said, ‘Martin, you really believe that if I was somewhere and a white guy spat on my face, you think I would walk away from that?’” Reeves recalled. “I said I’d try and kill that son of a b****.”

When Reeves became publisher and CEO of The Miami Times after his father’s death in 1970, he encouraged his staff to look at journalism through a different lens. For example, instead of labeling Blacks’ response to the acquittal of four white cops who murdered Black insurance salesman Arthur McDuffie in 1980 as ‘riots,’ Reeves ensured his paper referred to them as ‘protests,’ ‘uprisings’ or ‘civil disobedience.’ Under his leadership, The Miami Times also ended the careers of a police chief and mayor and cost the City of Miami Beach millions by supporting a tourism boycott.

Mohamed Hamaludin, who served under Reeves as The Miami Times’ executive editor for 15 years, recalled his former employer’s commitment to justice fondly.

“When that newspaper started in 1923, I think there was no voice. There was nothing for the African American community. Garth Reeves decided he was going to change all of that when he came back from the war. … And he decided that this was going to be a voice for the community. And he wanted it also to be a place where they can exchange news among themselves, learn about themselves,” Hamaludin said during an interview with National Public Radio (NPR).

A HANDS-ON ACTIVIST

Reeves operated under the biblical principle “To whom much is given, much will be required.” He put his money and actions where his pen was.

It was not uncommon for him to make hefty donations to causes that advanced the trajectory of Black people. In the 1980s, he donated $600,000 to his collegiate alma mater, which was matched by $400,000 from the state. This created the Garth C. Reeves Eminent Scholars Chair in the FAMU School of Journalism & Graphic Communication (SJGC). According to FAMU, it was the first endowed chair in the school and the first ever endowed by an alum.

He continued giving back over the course of his life. When he was 98, he donated $45,000 to the Black Archives, History and Research Foundation of South Florida. He encouraged other people to do the same.

“Though I sold my papers for a nickel, I’ve made some money in this town. This town has been good to me and I wanted to give back. Everybody should have that idea,” Reeves said.

Reeves was also the first black leader to sit on many of Miami’s boards including: the United Way of Dade County, Barry University, the Boy Scouts, the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce and MiamiDade College.

He worked tirelessly to change the trajectory of Blacks in Miami and the nation through his heavy involvement with organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. and Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, Inc.

He was also a founding member of the Episcopal Church of the Incarnation in Miami; a longtime member of the National Newspapers Publishers Association (NNPA) and headed the Amalgamated Publishers of New York City for 10 years. Both NNPA and the Amalgamated Publishers are committed to the advancing the cause of the Black Press.

Honors and Accolades

For his lifelong service and advocacy, Reeves was inducted into the Hall of Fame by the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) in 2017. He also received honorary doctorates from FAMU, the University of Miami, Barry University and Florida Memorial University.

Though he’d ‘officially’ retired, it was in name only. Even at 100, Reeves was still committed to improving the plight of his people.

Two months before he died, he told two young journalists to stop by The Miami Times the following week and tell the staff he’d sent them. He was still connecting the dots, offering opportunities and looking out for those in his community. Hamaludin said this was typical of him.

“I think Garth Reeves was very sharply focused to try to get the African American communities to see that, you know, they have a role to play to develop themselves, that they should go after jobs and get money. He said that being poor is no fun; being rich is better,” Hamaludin told NPR. “He wanted the African American community to go after education. He wanted the white community to treat (the) African American community as equals, integrating the school system. And all of these things came to pass during Garth Reeves’ tenure at The Miami Times.”

Reeves himself never wanted people to let their flames dim in their fight for justice. “I’d like to see our news continue to fight for the rights of the people in our community and never to become complacent and feel that the struggle is over,” he once said.

It’s So Hard To Say Goodbye Reeves was preceded in death by both of his children. His son Garth C. Reeves Jr. died at 30 in 1982 of colon cancer and his daughter Rachel J.

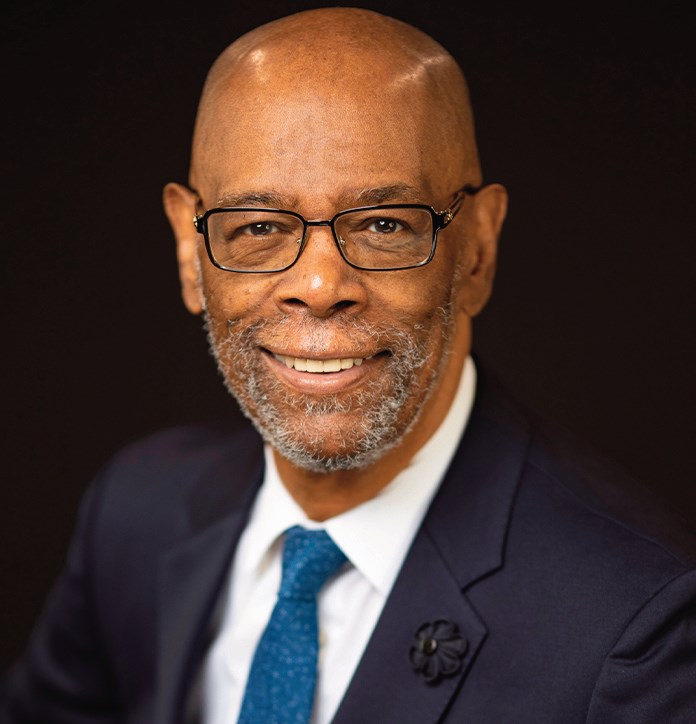

Reeves died two months before him in September at 69. He is survived by his grandson Garth Basil Reeves, 29, who now helms the mantle of his family’s historic legacy.

Services include a litany at 6 p.m. on Thursday, Dec. 5, at The Church of the Incarnation, located at 1835 NW 54 Street in Miami and a funeral at 10 a.m. on Friday, Dec. 6, at the Historic St. Agnes Episcopal Church, located at 1750 NW 3rd Avenue in Overtown.

No Comment