Refreshingly diverse crowds have embraced the trending hashtag extolling the value of black lives across the nation. #BLACKLIVESMATTER strikes a powerful chord as it appears that a blatant disregard for the lives of African Americans contributed to two grand juries’ refusal to hold police officers accountable for ending the lives of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and Eric Garner in New York City, both unarmed black males.

Had hashtags existed in 1966 when university Professor Maulana Karenga created Kwanzaa, #BLACKLIVESMATTER could have served as the impetus for the week long holiday created specifically to emphasize the inherent value of African American heritage. With the apparent need for a reminder that America’s darker hued citizens are worthy of its declarations of equality, Kwanzaa takes on new meaning this year.

Kwanzaa begins the day after Christmas and lasts for seven days, with each day devoted to the celebration of a different principle. This year’s theme is “Practicing the Culture of Kwanzaa: Living the Seven Principles.”

One of South Florida’s strongest Kwanzaa proponents is William “DC” Clark, who was drawn to the cultural celebration when he was a young firefighter and a member of the Progressive Black Firefighters in the mid-80s. Because he and a few others wanted a more vigorous approach to social change, they left the group to form I AM (International African Movement) MIAMI.

Clark said that today’s protests strike a familiar chord.

“Ironically, in the late 80s, you had a lot of killings of black unarmed youth and men at the hands of the police here in Miami, which spurred us to go into the streets to protest the same things that they’re protesting now.”

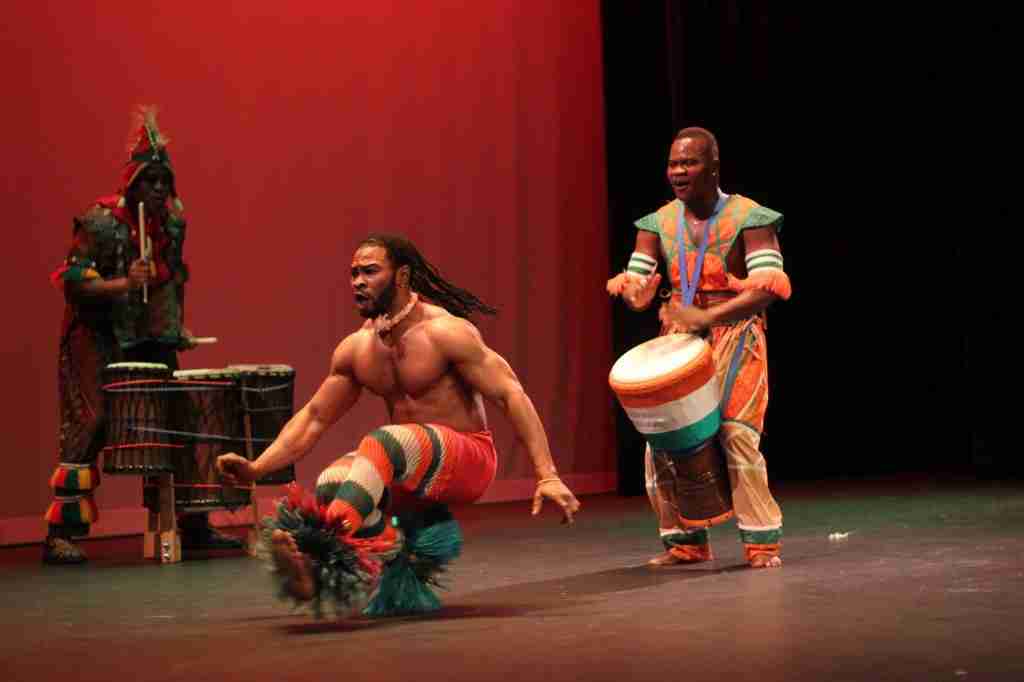

I AM MIAMI also created and hosted Miami’s first Kwanzaa Ball, a lavish family affair where community members decked out in African garb celebrated the seven principles.

I AM MIAMI also created and hosted Miami’s first Kwanzaa Ball, a lavish family affair where community members decked out in African garb celebrated the seven principles.

Clark pointed out that the nationwide protests of the murders of unarmed black males is being sustained because the protesters have, perhaps unwittingly, embraced one of the seven Kwanzaa principles.

“Many people, when these protests first started, they thought it was going to be business as usual. In other words, black people would go out in the street for a couple of days, maybe a week or two, get that frustration off of their chests, and then go back to our mundane lives where nothing has really changed,” Clark explained. “But in the past few weeks…things have changed. This protest is being sustained by a common core, or in this case ‘Nia,’ the Kwanzaa principle that means purpose.”

Charlene Farrington Jones, director of the Spady Cultural Heritage Museum in Delray, said that the protesters have also embraced Imani (Faith) in what they’re doing; and the entire country would benefit if it embraced Umoja, which means ‘unity.’

“Obviously, if everyone here in the United States had any concept of what unity meant, they could never do some of the things that they do to other people; and it’s really not a race things, it’s a humanity thing,” she said.

Clark, who believes in the Kwanzaa principles so strongly that he named his oldest daughter, ‘Nia,’ shares a similar perspective on Kwanzaa’s first principle.

“All seven principles are relevant, but the first one, Umoja…to strive for and to maintain unity in the family, community, nation and race; if you had that, just that alone, you would see a better community, a more respectful community,” he explained.

He also believes that black people “can accomplish anything we put our minds to. We have an untapped resource of power that we fail to see within and to use,” he said.

“I wish this movement could continue and we could then really fully embrace self-determination (Kujichagulia) and cooperative economics (Ujamaa),” said Jones. “I do believe that if we came together as one and pooled our resources as one, we would be an unstoppable force.”

No Comment