(AP) _ Being shackled to a rock by your father as a 6-year-old in 98-degree heat might not be a part of a typical family vacation in the Bahamas – but April Yvette Thompson didn't have a typical family.

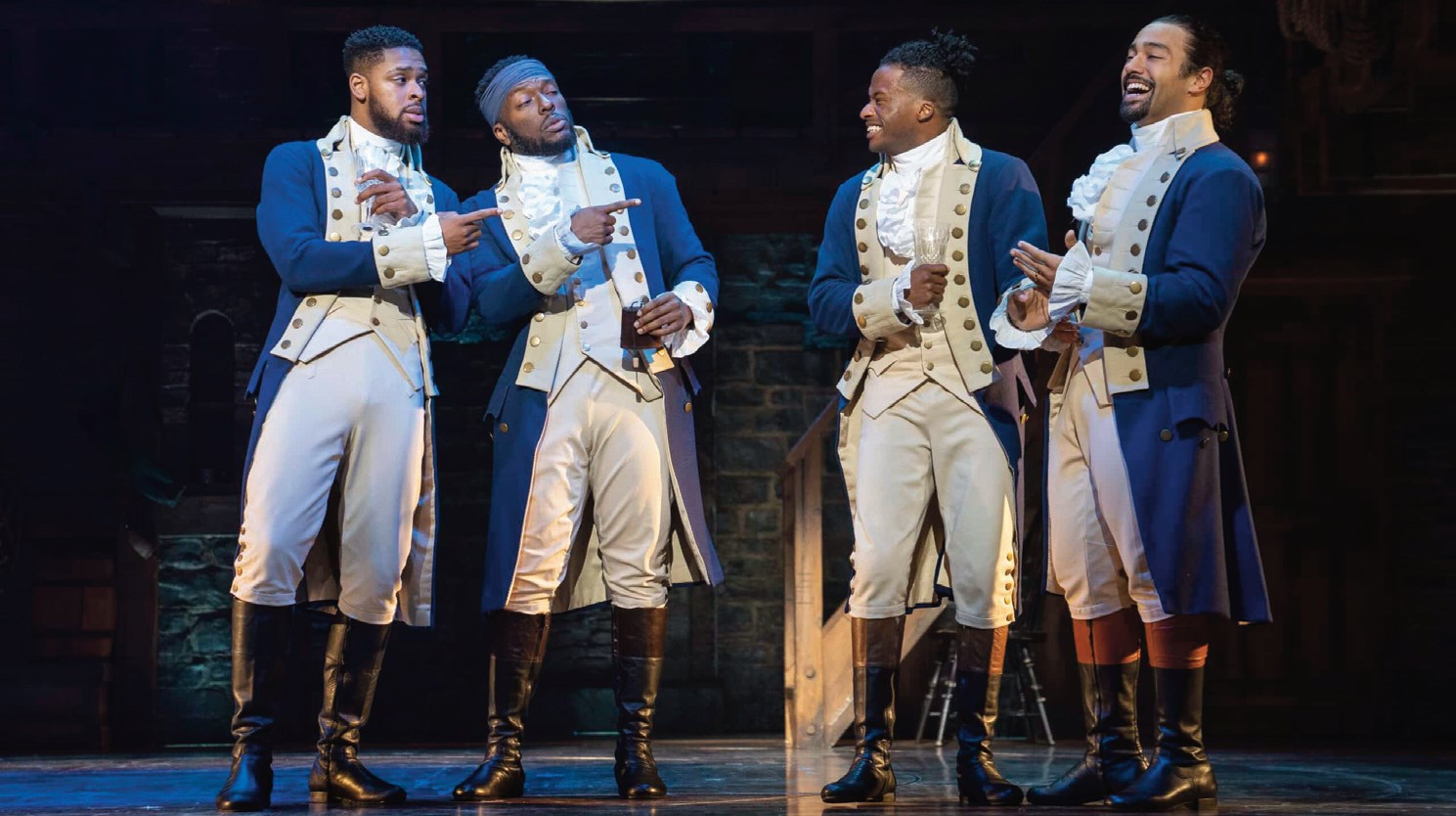

In “Liberty City,” a powerful and compelling new one-person show now on view at off-Broadway's New York Theatre Workshop, the magnetic Thompson takes us on a tour of her girlhood in the Liberty City section of Miami. Through a wonderfully varied cast of characters we are introduced to a singular clan – and a singular period in history.

Thompson embodies each person completely and seamlessly transitions from one to another, thanks to sensitive direction by co-author Jessica Blank. Never changing her casual clothes, she uses accents and mannerisms to portray her parents, her aunt Valerie, her adoptive grandmother Carolyn and herself. The audience gets to know and care about each individual through Thompson's strong, specific characterizations.

Brought up in an activist household by a black mother and a Bahamian-Cuban father, young April grows up in the 1970s learning about African heroes, community involvement and the shameful legacy of slavery. Her father, Saul, is a tenacious community organizer who serves on the city council and teaches April to stand up for herself and always speak her mind.

In Saul, there exists “the expectation of good,” as his wife Lily says. Despite his later failings, his fight for justice is the moral center of this production.

The revolutionary spirit binding Thompson's family begins to splinter when Saul is removed from the city council for demanding that corporate chains hire blacks in black neighborhoods. He starts an affair and moves in with his girlfriend.

Lily turns to a “cult church” and drags April along to knock on doors on Saturday mornings. April's fractured family mirrors the fragmentation of the neighborhood caused by a lack of jobs and the prevalence of crack.

The simmering resentment boils over into the Miami riots of 1980 – sparked by a not guilty verdict for four white policeman accused of beating Arthur McDuffie, a black man, to death. These riots seem all the more terrifying as seen through April's 11-year-old eyes as she struggles to get herself and her brother home from school through streets filled with chaos.

Antje Ellerman's evocative set includes Carolyn's kitchen, Saul and Lily's living room and a tiny piece of Valerie's condo, with a backdrop of a chain link fence. Behind all this is the Brotherhood Supermarket, complete with a painting of Martin Luther King. We also get a tiny sliver of beach with a rusted shackle. Above the stage are wide screens for Tal Yarden's projections of Liberty City skylines, archival footage of the riots and the ocean surrounding the rocky island of Eleuthera, in the Bahamas.

In that last location, Saul is teaching April about her ancestors. They were slaves who were left chained to rocks in the open air; if they survived, they were sent on to work in America.

These themes of survival and self-knowledge provide an apt ending to this exceptionally stirring and vivid tribute to a family and a time.

No Comment