In some child welfare circles, ‘family preservationist’ is a dirty phrase.

In some child welfare circles, ‘family preservationist’ is a dirty phrase.

Many within the complex system have scoffed at the idea that “abused and neglected” children, especially if they are poor and black, belong with their families.

These comments come despite growing evidence that children who grow up in the foster care system are more likely to be homeless, dependent on public assistance and incarcerated than their non-foster care raised counterparts.

“I think whenever you can keep a family together, it’s a victory,” said Alan Abramowitz, Miami’s regional administrator for the Department of Children and Families, and a proud family preservationist.

During an interview at Miami’s Afro in Books Café, he told the South Florida Times that coming from a military family with strong public service beliefs shaped his career choices.

After two people he knew committed suicide, he worked for a crisis hotline “doing suicide intervention for years,” the former criminal defense attorney said.

His tenure at DCF began similarly after the highly publicized 1998 death of six-year old Kayla McKean at the hands of her father.

“That day, I sent a letter to [then] Secretary Kearney and they hired me to be the chief legal counsel for DCF,” he said.

Abramowitz, however, soon decided to move beyond the legal arena.

“I realized that giving legal advice is good, but I really wanted to be the decision maker. I thought I could make more of a difference if I was the one to implement my philosophies,” he explained.

ROVING CRUSADER

For the past five years, he has been implementing those policies wherever he is needed.

“I’ve always made that offer to whoever is the secretary. I’ll go wherever I’m needed. I consider this public service,” he said.

Abramowitz said Robert Butterworth, the current DCF secretary, shares his beliefs about families. Of Abramowitz, Butterworth said, "We have seen his leadership excel in Pinellas, Palm Beach and Brevard counties and I expect he will work to keep families together here in Miami-Dade and Monroe as well."

Abramowitz’s success in those other districts is already being repeated in Miami. “In Miami, the first three months of 2007, we averaged removing 130 children a month. So far the first three months of 2008, we have averaged removing 89 children a month…a reduction of about 32%," Abramowitz said.

“[DCF] Secretary Butterworth believes in family preservation, and believes that the state cannot make a good parent,” Abramowitz said, acknowledging that DCF’s top brass has not always been so pro-family. “There are so many families that could have been kept together that we have failed.’’

He recognizes that some families are incapable of providing a safe place for their children without state intervention.

“We will still have to remove some children from families, unfortunately. But it’s not as many as we do,” he said.

One of his philosophies includes partnering with parents who have come to the state’s attention because of suspicions of child abuse or neglect.

“We’ve got to meet with parents, we got to find out what they need and we’ve got to partner with them,” he said.

Abramowitz, 46, balks at the system’s tendency to paint the parents it encounters as monsters who do not care for their children.

“The majority of the time, they love their children,” he said.

He is also mindful that many children enter the system due to poverty-related issues that the system classifies as “neglect,” noting that, “We should see it as a poverty issue and not an abuse or neglect issue.”

RELYING ON THE EXPERTS

He has implemented an effective approach to keeping families with serious problems – like drug addiction – together.

When a child abuse investigator encounters a mother battling substance abuse, for example, Abramowitz said that instead of an investigator deciding on her own to remove a child, “You’ve got to get the substance abuse treatment people that understand recovery to get at the table with the family to come up with a solution to keep that family together.”

It’s an approach he has tried in other areas, with significant results, “In Palm Beach County, we reduced children in out-of-home care by 33 percent,” he said.

In Volusia County, he said, the area had a severe substance abuse problem.

“We came up with a crisis response team. When [investigators] go out in the middle of the night, within an hour, we can get people there who are expert,” he said.

His belief in the strategy’s effectiveness proved true. According to Abramowitz, “We were able to keep more families together. The numbers were astonishing.”

Those numbers included a decrease in the amount of children in out-of-home care from 1200 to 1040; and a reduction in the number of children involved in the dependency system from 2000 to 1515.

The married father of two has widespread support. Miami’s administrative judge for dependency court, Cindy Lederman, said in an emailed statement, “Alan Abramowitz has been a gift to this community.”

When asked to elaborate on why Abramowitz is a gift, Lederman replied, “He has extensive knowledge and experience in the child welfare system and he REALLY cares about our children and families.”

Richard Wexler, a former award-winning journalist who now runs the Virginia-based National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, agreed.

“When it comes to understanding how important it is to children to keep their families together, everybody in child welfare talks the talk. Alan Abramowitz walks the walk,” Wexler, an outspoken family preservationist, told the South Florida Times.

In his book, Wounded Innocents: the Real Victims of the War against Child Abuse (Prometheus Books: 1990, 1995), Wexler describes the devastation the child welfare system has wreaked upon families across the country, “under the guise of child protection.”

Many of the more than two dozen awards Wexler won during his 19 years of reporting were for stories about child abuse and foster care.

For Abramowitz, walking the walk has meant impressing upon his investigators the trauma that removal inflicts upon children.

“The studies have come out over the past few years to show we have actually been doing a disservice to families,” Abramowitz said.

One such study, the March 2007 Child Protection and Child Outcomes: Measuring the Effects of Foster Care, looked at outcomes of more than 15,000 children and concluded that,

“Those placed in foster care are far more likely than other children to commit crimes, drop out of school, join welfare, experience substance abuse problems, or enter the homeless population.”

Abramowitz wants to change the department’s role in these outcomes.

He said, “We can develop that reputation of being there for families, to help families.”

RMHarris15@Aol.com

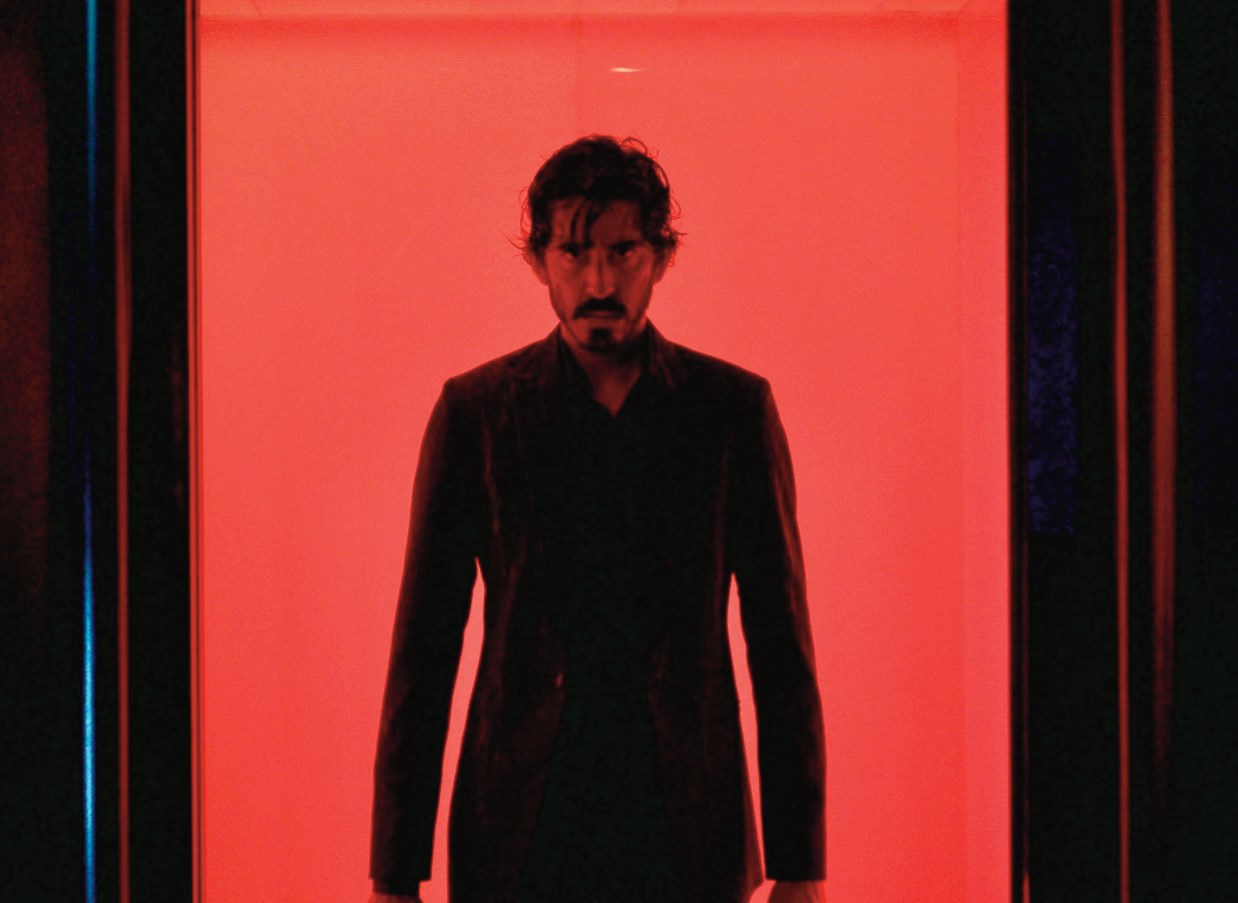

Photo: Alan Abramowitz

No Comment