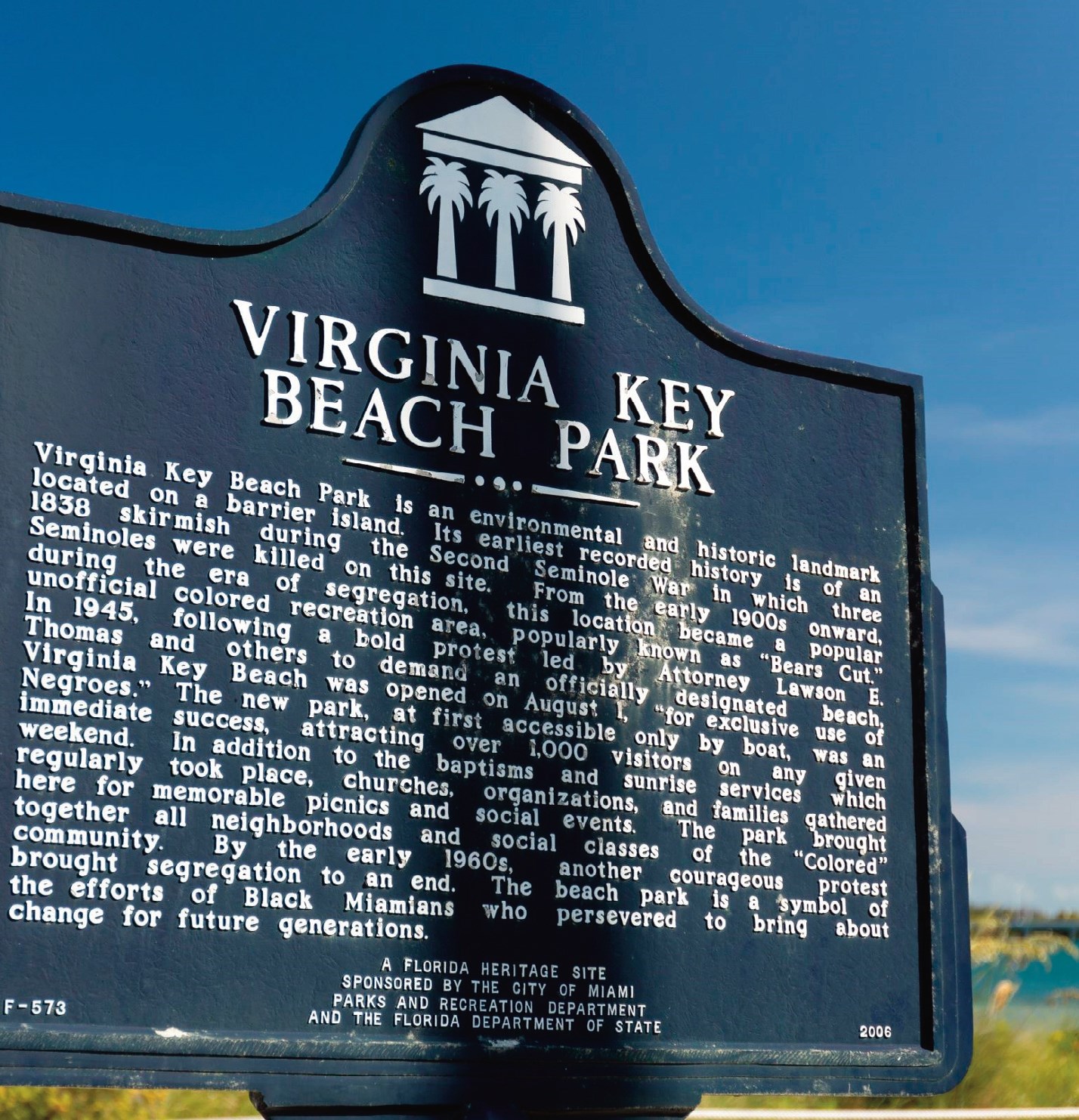

MIAMI, Fla. – In its first step to building a proposed Black Civil Rights museum at historic Virginia Key Beach, Miami’s only Colored beach during segregation, the Virginia Key Beach Park Trust hosted a community workshop to collect feedback on ideas to help draw up blueprints for the facility.

But two former Trust members dropped a bombshell on the Black community at the Sept. 30 workshop at the site: The proposed facility on the 82-acre barrier island is not exclusive to Black history, but covers the entire cultural history of Miami – including the history of Native Americans, environmentalists’ efforts to protect the ecology, and Black and White pioneers of Miami.

Gene Tinnie, artist, community activist and former Trust member, told the more than 100 people on hand, mostly Blacks, that the facility was proposed to tell broader stories of the history of Miami.

“It wasn’t only about the Civil Rights movement, there were longer stories to tell,” Tinnie said.

“It was proposed as Black history, white history and environmental history,” Tinnie said. “The original plan wasn’t limited to the civil rights struggle, it was to include Native Americans, intelligent people and the environment that made Miami what it is today.”

“IT WASN’T ONLY ABOUT THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, THERE WERE LONGER STORIES TO TELL.” – GENE TINNIE, ARTIST, COMMUNITY ACTIVIST AND FORMER VIRGINIA KEY BEACH PARK TRUST MEMBER.

Harold Braynon, also a former Trust member, said the Black Civil Rights museum concept was added to the cultural center proposal years ago.

He said the Black community somehow got the perception the building was to be similar to other Black museums, such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C., and the African-American Museum of the Arts in DeLand, Fla.

Braynon said at one point during his tenure on the board, the county set aside about $10 million for the project, but City of Miami officials stymied it.

“The Black Museum was never the initiative focus,” he said. “The focus was on the cultural history of Miami and environmental issues.”

Braynon said the previous Trust, which was replaced by Miami commissioners, was blamed for delaying the project, but only elected officials were empowered to make decisions to get it done including the funding.

Former Miami Commissioner and community activist Athalie Range created the Trust to restore the park and beach after city officials closed it in 1982 because of financial hardships.

Developers reportedly targeted the area to build hotels and condominiums, but Range advocated to preserve the land as part of Black history in Miami including segregation, the Civil Rights Movement and where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and former boxing champion Muhammad Ali swam when they visited Miami because they, like other Blacks, were banned from beaches in Miami Beach and Key Biscayne.

The 250,000-square-feet Black museum/cultural center proposal was part of the renovations to show the history of Miami and Virginia Key Beach including pictures, books, videos, artifacts and the story of Bahamian settlers who came to Miami before it was incorporated in 1896.

But some Black residents who participated in the workshop were surprised to hear the proposed facility is not exclusive to Black history.

Their sentiment is that, given that the project is proposed on Miami’s only Colored beach, the museum should focus only on Black history.

“I thought it was supposed to be a museum showing the struggles we went through,” 68-year Mattie Taylor, who swam at the beach when she was a little girl growing up in Overtown, told the South Florida Times. “I would still like to see us have a museum of our own history.”

Denise Gloria Henderson said a Black history museum is essential now, given the state’s controversial African-American History curriculum for public schools, which asserts that Blacks benefited from slavery by learning job skills.

“Kids need to learn the real history in Florida,” said the retired teacher. “We all learn about other people’s history and we want a building to tell our entire history. Not with other Miami history.”

Participants were organized into groups to discuss the type of museum they embrace and would not support. Most of Black participants agreed the city should restore the vision of the park from the 1950s and 1960s, regardless of what type of building is planned to go up on the land.

The concern also is that when the civil rights portion of the museum is built, it does not whitewash Black history, similar to the Black history course adopted by Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and the state education board.

“This is our history and we want to preserve it,” said one woman. “Black history in Miami is the park and it should stay that way.”

A coalition of environmentalists also weighed in and suggested the museum should also focus on the history of their efforts to protect the wildlife and other sensitive environmental issues on Virginia Key Beach.

Environmentalists said Virginia Key has one of the largest mangrove wetlands in the state, for example, which also attracts tourists and boosts the local economy.

They have launched cleanup efforts at the beach, where hundreds of volunteers including middle and high school students pick up tons of trash each week to make sure animals are safe from pollution along the shorelines.

Some environmentalists also expressed concerned about the risk of building near the coast of Miami, given the potential threat of sealevel rise and storm surges in coming years.

They project that Miami, the most vulnerable coastal city nationwide, will gain between 8 to 12 inches of regular flooding by 2040, threatening the city’s billion-dollar waterfront real estate value and economy.

They urged city officials to tackle the climate change issue ahead of building the center.

“Climate change is already hurting the environment and it’s getting worse as time goes on,” said environmentalist Vivian Chelsey.

Miami officials hired Lord Cultural Resources, the international consulting firm responsible for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C., to help the city build the cultural museum.

Tiffany Lyons, a consultant with the firm, said Miami earmarked $20 million for the building.

Lyons said once her firm examines the input from the community, it will develop and present a preliminary plan at another workshop late this year, and a master plan for the building in 2024.

She said that is “the next step to getting the center built,” and it should take about 24 months to complete the project.

Despite the debate on which culture would mostly benefit from the museum, some participants pledged sums of money to help build the center.

One white man said he will donate $30,000, and one Black woman pledged $10,000.

“Together, with input from the community, we will realize the dream of having a museum that tells our story in that space,” said Miami Commission Chairwoman Christine King, who also chairs the Trust, after the meeting. “We value the feedback and all perspectives from attendees as we look forward to the next actionable steps.”

Patrick Range, grandson of Athalie Range and former chair of the Trust who protested the removal of his board at commission meetings, said it’s time for the building to go up.

“Let’s move this vision forward … that’s what the Trust is all about,” Range said. “Let’s get it done and show the world where we came from.”

No Comment