By SAM FRIEDMAN

Fairbanks Daily News-Miner

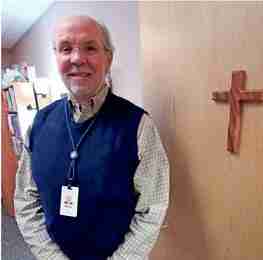

FAIRBANKS, Alaska (AP) – It took David Rumph Jr. more than five decades to learn that his calling in life is to help people die. Rumph is the chaplain at Hospice Services for Fairbanks Memorial Hospital. He’s a former photo lab worker, military policeman and pet supply retail worker who was led to hospice work by both his own experience with the death of family members and his sense of community service.

At any given time Rumph and other hospice staff members help as many as 45 people who are dying from terminal illnesses, reported the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner (http://bit.ly/2frIrdn). Hospice is based on a philosophy of treating patients rather than diseases, helping patients die with dignity and free of pain. What Rumph does to help varies greatly among families. Sometimes he performs bedside religious services. Once a month, he meets with a group of male surviving family members at Denny’s. Much of the time he just listens actively, a method he calls “companioning.” “Patients elect for this service,” he said. “We are invited guests into what I consider to be a sacred time and space. Many times there are hospital beds set up in the living room in front of the big window so that grandpa can look out.” Rumph, 61, is from Kentucky. He was interested in ministerial work more than 20 years ago but life got in the way. As a young man, Rumph worked in photo laboratories, served in the Army and attended and dropped out of college several times. When he was 35, he decided he wanted to be a Methodist minister. He received a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Northern Kentucky. His 18-year-old daughter killed herself when he was part- way through a Master of Divinity degree.

Rumph’s marriage fell apart and for three years he experienced complicated grief, a disorder he sometimes encounters among family members he helps today.

Rumph credits Alaska with helping him recover from the grief. In 2001, he visited Alaska with his brother, who worked as a dog handler for Susan Butcher. Rumph planned to visit for two weeks but he ended up staying for two months and later moved to Fairbanks. Rumph worked as a clerk at Cold Spot Feeds and as an educator at First United Methodist Church. He went back to school and completed his master’s in divinity in 2005.

In 2004, he began volunteering for Hospice of the Tanana Valley, the organization that later was folded into Fairbanks Memorial Hospital’s hospice services. Working in hospice was a natural fit for Rumph.

“I’ve known death,” he said. “There was nothing scary or taboo about death itself. It felt like a unique and significant way to love my neighbor.” Fairbanks hospice has transformed since it became part of the hospital program. As a volunteer, Rumph’s duties included driving patients to pharmacies and transporting medical equipment. The program was run out of a small office on Fourth Avenue.

Today the Fairbanks Memorial Hospital hospice program has a building on Gillam Way near the hospital. A team of about 20 medical workers, social workers and Rumph care for patients. Rumph was hired to be the program chaplain in January 2014.

When new patients enter hospice, they usually have less than six months to live, but death is unpredictable. Sometimes patients get better and “graduate” from hospice care. The program recently re-admitted a patient who is bedbound again after improving enough under hospice care to walk with a cane.

After a death, Rumph is available for grieving friends and family members for as long as they need him.

No Comment