Jarvis Swain, 63, has been working for FPL for more than 41 years. As an electrical engineer, he prepares each year to serve FPL customers during Florida’s hurricane season. PHOTOS COURTESY OF FPL

Staff Report

As Hurricane Andrew ravaged South Florida in August 1992, one electrical engineer found himself at the epicenter of that historic, catastrophic, Category 5 storm. It was the first time Jarvis Swain, a Georgia native, experienced a hurricane of that magnitude and little did he know it would change his life forever.

“Andrew was unprecedented and it left a lasting impression,” Swain, a principal engineer for Florida Power & Light Company’s power distribution unit, said. “It taught me to never underestimate the power of Mother Nature and although I didn’t know it then, it wouldn’t be the last time I’d see the power of a catastrophic hurricane.”

In the past, Swain’s storm role for FPL was to patrol main power lines. He’d drive along the power lines route looking for damage and pinpointing anything that may cause an outage. Then, he’d report it to the storm command center, which would assign a lineworker crew to fix it.

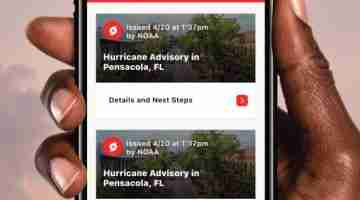

Three decades later, he patrols main power lines electronically from the comfort of his desk. A system of smart switches installed on FPL’s grid detects potential outages before they even happen, and a fleet of drones monitor FPL’s 88,000 miles of power lines.

In his current role, Swain helps FPL leaders improve the utility’s power grid, making it more resilient in preparation of future disasters by providing comprehensive reports about where outages happen and where the company needs to focus its efforts.

In his 41 years of service at the company, Swain has experienced firsthand the effects hurricanes can have on an electric power grid.

“We had three hurricanes affecting FPL’s service territory in six weeks in 2004 and nearly every corner of the state felt the impacts. We were back-to-back from August to October with nothing but a week of rest here and there,” he said. “The following year, we had Wilma, a 3week storm, which is unheard of. If anything, these hurricanes pushed us to ensure the grid’s reliability and safe operation during daily operations as well as extreme weather conditions.”

“In his 41 years of service at the company, Swain has experienced firsthand the effects hurricanes can have on an electric power grid.”

After the historic 20042005 hurricane seasons, when seven storms hit the state of Florida, FPL began the journey of improving its day-to-day reliability by hardening main power lines and installing more than 200,000 intelligent devices that can detect and prevent power outages.

“If we have better day-today performance, it means we have to spend less time on restoration once a storm hits,” Swain said.

Every year, FPL prepares for the upcoming hurricane season with a companywide storm drill designed to test the company’s response to a simulated hurricane. The weeklong drill is an important part of the utility’s year-round training ensuring employees are ready to respond when customers need them most.

Like many of the more than 3,500 employees participating in the drill, Swain has a day job as well as a storm job. During hurricanes, he’s part of the Storm Situation Unit where he provides leaders the data and analysis they need to make critical decisions, such as pinpointing strategic locations for staging sites as well as where to deploy restoration crews, resources and staffing.

“Jarvis and I joined FPL the same year and it’s been a pleasure working with him ever since. He has played a critical role in the success of our power delivery team, helping us provide customers with the most reliable service in the country,” Manny Miranda, FPL Executive Vice President of Power Delivery, said. “His dedication, passion and commitment embody the values of our organization.”

The Ida-Nicholas combo came after Louisiana was hit in 2020 by five hurricanes or tropical storms: Cristobal, Marco, Laura, Delta and Zeta. Laura was the biggest of those, packing 150-mph winds. After Laura, relief workers had set up a giant recovery center in a parking lot of a damaged roofless church when Delta approached, so all the supplies had to be jammed against the building and battened down for the next storm, said United Way of Southwest Louisiana President Denise Durel.

“You can’t imagine.

You’re dumbfounded. You think it can’t be happening to us again,” Durel recalled 2½ years later from an area that is still recovering. “The other side of it is that you can’t wish it upon anyone else either.”

Florida in 2004 had four hurricanes in six weeks, prompting the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration to take note of a new nickname for the Sunshine State – “The Plywood State,” from all the boarded-up homes. “We found a trend,” Lin said. “Those things are happening. They’re happening more often now than before.”

There’s a caveat to that trend. There haven’t been enough hurricanes and tropical storms since about 1950 – when good recordkeeping started – for a statistically significant trend, Lin said. So her team added computer simulations to see if they could establish such a trend and they did.

Lin’s team looked at nine U.S. storm-prone areas and found an increase in storm hazards for seven of them since 1949. Only Charleston, SC, and Pensacola, Fla., didn’t see hazards increase.

The team then looked at what would happen in the future using a worst-case scenario of increasing carbon dioxide emissions and a more moderate scenario in line with current efforts worldwide to reduce greenhouse gases. In both situations, the frequency of back-to-back storms increased dramatically from current expectations.

The reason isn’t storm paths or anything like that.

It’s based on storms getting wetter and stronger from climate change as numerous studies predict, along with sea levels rising. The study looked heavily at the impacts of storms more than just the storms themselves.

Studies are split on whether climate change means more or fewer storms overall, though. But Lin said it’s just the nastier nature and size that increases the likelihood of back-to-back storms hitting roughly the same area.

Any increased frequency in sequential storms in the past was likely due to a reduction in traditional air pollution rather than humancaused climate change; when Europe and the United States halved the amount of particles in the air since the mid-1990s it led to 33% more Atlantic storms, a NOAA study found last year. But any future increase will likely be more from greenhouse gases, said two scientists who weren’t part of the study.

“For people in harm’s way this is very bad news,” University of Albany hurricane scientist Kristen Corbosiero, who wasn’t part of the study,

said in an email. “We (scientists) have been warning about the increase in heavy rain and significant storm surges with landfalling TCs (tropical cyclones) in a warming climate and the results of this study show this is the case.”

Corbosiero and four other hurricane experts who weren’t part of the study said it made sense. Some, including Corbosiero, say it is hard to say for sure that the back-to-back trend is already happening. Colorado State University hurricane expert Phil Klotzbach said the emphasis on worsening effects on people was impressive, with storm surge from rising seas and an increase in rainfall from warmer and stronger major hurricanes.

“You have to have faith and be able to move forward. You’ve just got to be in constant motion,” Durel, the Louisiana United Way president, said. “Our neighbors mean much more than wallowing in aggravation.”

Identifying and responding to the areas most affected by the storm is not only crucial for FPL and its customers, but also for county and state leaders or agencies making contingency plans to minimize disruptions and ensure public safety.

“We help them see the big picture,” Swain said. “One of the things Manny (Miranda) likes to see is our 10-year comparisons showing how FPL’s reliability has progressed. The reports show we’re doing better than before.”

Miranda and his team lead the company’s hurricane restoration efforts. Since 2006, the hardening investments implemented by the Power Delivery team has improved day-to-day reliability by 41%.

“In Florida, it’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when a storm will hit,” Miranda reminded FPL employees and invited guests during this year’s storm drill. “Although we’ve gotten much better over the last 20 years, no system is stormproof. Hurricanes will always result in outages, but that’s why we have our storm drill and why we’re always working to improve how we prepare and respond.”

At 63 years old and with dozens of storms under his belt, Swain doesn’t plan on stopping yet. He loves the people he works with, and his job gives him purpose.

“There are great people behind FPL. Committed people. They work hard and long hours to get your power restored,” Swain said. “It’s more than a company you pay to have power every month and that’s why we say every day we don’t have a hurricane, is a day we prepare for one.”

No Comment