“She couldn't vote before 1965, just as I couldn't,” said the Rev. Jesse Jackson, referring to the Voting Rights Act that abolished poll taxes, literacy tests and other ways whites in Southern states kept minorities from voting.

Jackson and other critics have said the law is merely a new, covert effort to take away the right to vote from older blacks and poor people, groups who historically tend to vote for Democrats and are less likely to have a driver's license, passport or other government-issued identity cards.

Both of Haley's parents were born in India and came to South Carolina before she was born. Haley — a Republican who became the state's first female governor — never dwells on her heritage but she has mentioned it in her inaugural speech or stories from her childhood. Almost all have the same theme of overcoming adversity.

She refused an interview for this story, instead sending a statement through her spokesman, Rob Godfrey, defending her support of South Carolina's law requiring photo identification at the polls. The governor has said the measure is needed to prevent voter fraud.

“Those who see race in this issue are those who see race in every issue but anyone looking at this law honestly will understand it is a commonsense measure to protect our voting process. Nothing more, nothing less,” Godfrey said in the statement.

Haley has invoked strong rhetoric against the federal government and the Obama administration on the voter ID issue and two others. A federal judge temporarily put a halt to the state's law cracking down on illegal immigrants and the National Labor Relations Board fought Boeing Co.'s efforts to build a plant in North Charleston that would employ 1,000. The board had claimed Boeing built the plant in South Carolina — a state where workers are not required to join unions — to retaliate for past union disputes with its workers in Washington state.

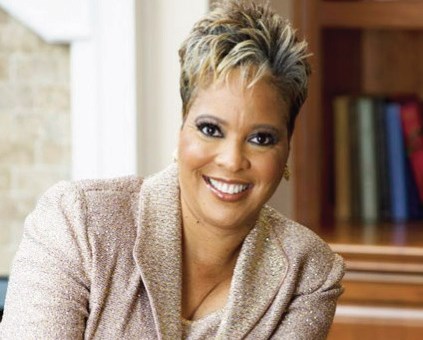

Leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) said after a Martin Luther King Day rally at the South Carolina Statehouse that they would expect a governor who experienced some prejudice growing up to have some compassion, especially when it comes to the voter ID law.

“At the end of the day, it's one more governor who is willing to deify the dreamer and desecrate the dream,” said Benjamin Todd Jealous, president of the NAACP.

Haley was born in 1972 and her first memories came more than a decade after the height of the civil rights struggle, when South Carolina finally gave up allowing only whites to vote. Her family lived in Bamberg County, where about 50 percent of the 16,000 residents were black, according to the 1970 Census. Her father wore a traditional Sikh turban and taught biology at the local historically black college, while her mother was a middle school social studies teacher.

During her 2010 campaign, Haley didn't make her heritage a point. But, when asked, she wouldn't shy away from how her brown skin affected her life. She told a story about her third-grade classmates refusing to play kickball with her until they figured out if she was black or white. She insisted she was brown and said instead of stewing about the problem she simply took the ball and ran onto the field. Her classmates followed and they played.

One story she has repeatedly told is how she and her sister entered a children's beauty pageant in Bamberg County, which crowned black and white winners. Organizers didn't know where to put the girls, so they were disqualified.

“I grew up knowing that we were different. But it's also the reason why I think that I focused so much on trying to find the similarities with people as opposed to the differences,” Haley said during the campaign.

Haley also wasn't around to hear Southern state governors such as George Wallace in Alabama rail against the federal government during the civil rights movement. In June 1963, Wallace briefly blocked a doorway at the University of Alabama as the National Guard tried to help two black students inside to register. He called the federal intrusion “unwelcomed, unwanted, unwarranted and force-induced.”

NAACP leaders said Haley's fiery pledges to fight the federal government reminds them of that time five decades ago.

No Comment