The Biden administration announced on Sept. 24 the creation of an Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights within the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The office will merge three EPA programs: the Office of Environmental Justice, External Civil Rights Compliance Office, and Conflict Prevention and Resolution Center. An assistant administrator and a staff of 200 will operate on a $3 billion budget carved out of the Inflation Reduction Act.

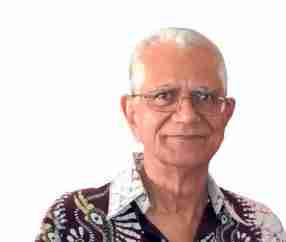

The announcement from the EPA’s first African American administrator, Michael S. Regan. “We are embedding environmental justice and civil rights into the DNA of EPA and ensuring that people who’ve struggled to have their concerns addressed see action to solve the problems they’ve been facing for generations,” Regan said in a statement.

The generational problems have plagued many parts of the country. For example, activists won a court order forcing the city of Miami to close its “Old Smokey” trash incinerator which began polluting a predominantly African American section of Coconut Grove in 1925. A battle ensued over cleaning up the toxic ash left from more than 50 years of operation.

Miami-Dade County, in the 1980s, approved a 330,000-square-foot plant to convert 250,000 tons of trash into fertilizer using bacteria — across the street from Skyway Elementary school in Carol City, a majority African American neighborhood. Despite the company’s assurances, the plant gave off odors which were blamed for sickening the children. Then principal Frederica Wilson – later elected to Congress – and students forced the plant’s closure.

The state built its first hazardous waste injection well In Mulberry, Polk County, a majority African community. In Pensacola, a Superfund site – an area contaminated by hazardous waste being dumped, left out in the open or otherwise improperly managed — was located next to a playground frequented by mostly African American children.

Overall, hazardous waste storage facilities and sewage treatment plants in Florida were located mostly in or near majority African American communities, The Orlando Sentinel reported in 1994, citing a study by then University of Central Florida Professor Elliot Vittes.

African Americans, Latino Americans and Indigenous peoples were “disproportionately affected” by pollution from the almost 10 billion gallons of fecal waste produced annually by 2,300 hog farms and deposited in 3,300 waste lagoons in North Carolina, the Washington, D.C.-based Environmental Group said, citing a 2014 report by University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, researchers.

And then there are small towns in Louisiana where the mainly African American population are 50 times more likely to get cancer than the rest of the nation, which some residents and activists blame on pollution from 150 chemical companies starting in the 1960s. "It is killing people by over-polluting them with toxins in their water and in their air. This is slavery of another kind,” said the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber. Residents nicknamed the stretch of land “Cancer Alley” and someone erected a roadside sign saying, "Bhopal on the Bayou?" – a reference to toxic gas killing 2,000 people in India in 1984. Also, over three years, 75 women – one in three in the St. Gabriel Parish had 75 miscarriages, The Los Angeles Times reported, A Louisiana Chemical Association spokesperson suggested the cause was too much sexual intercourse.

Environmental injustice is linked to segregated housing, biased decisionmaking and zoning and land use, says Robert Bullard, a Texas Southern University distinguished professor. “Race is still more potent than income in predicting the distribution of pollution and polluting facilities,” he writes in an online report.

African Americans are 79 percent more likely than European Americans to live where industrial pollution poses the greatest health danger, says Bullard, regarded as the father of environmental justice after he published his 1990 book “Dumping in Dixie.” He says in 19 states African Americans are more than twice as likely to live in neighborhoods with

high pollution levels and they are overrepresented in areas within a three-mile radius of the nation’s 1,388 Superfund sites. A majority live within 30 miles of dirty coal plants; others are disproportionately affected by pollution from the oil industry’s 150 refineries in 32 states. Protest against the environmental injustice which Bullard studies dates back to at least the Civil Rights Act of 1964 but he was the first to link the siting of hazardous operations to historical patterns of segregation in the South, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy has said.

But it was civil rights activist the Rev. Benjamin Chavis Jr. who actually coined the term “environmental racism” eight years earlier, describing it as “the deliberate targeting of people-of-color communities for toxic waste facilities,” along with “the history of excluding people of color from leadership in the environmental movement.”

Also, the new EPA initiative comes 38 years after another Democratic president, Bill Clinton, issued an executive order requiring federal agencies to develop "environmental justice" strategies, The Orlando Sentinel reported at the time. But the protests have continued because the pollution continues.

And if Bullard is the father of environmental injustice resistance, Dorceta E. Taylor must be its mother. During the 1991 inaugural National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C., Taylor helped develop the “Principles of Environmental Justice” which Essence reporter Samantha Willis described in 2019 as “a 17point document that has guided the movement’s vision and actions for nearly 30 years.”

And then there is this: One of the “Cancer Alley” chemical plants was built on the site of the Belle Pointe plantation, where planter André Deslondes owned 150 slaves. “Where once stood a West Indian style plantation house now stands a plant pumping a ‘likely carcinogen’ into the air,” the Guardian’s Oliver Laughland and Jamiles Lartey recalled in 2019. “The list of serious ailments and deaths from cancer are woven into the story of this town over the last 50 years — just the most recent of deprivations visited on African Americans who have lived and worked on this land for centuries.”

Still, it is not certain what the new EPA agency can accomplish. The recently installed U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority, on June 30, ruled against the EPA’s regulations governing carbon emissions from power plants, saying only Congress has such authority. And some polls have said that the regulations heating Republican Party could gain control of Congress in November.

No Comment