By THERESA VARGAS

The Washington Post

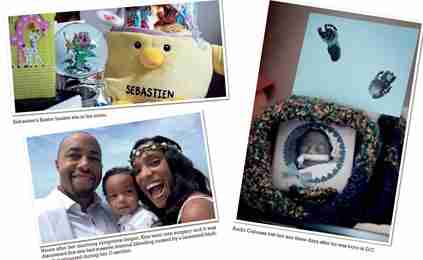

WASHINGTON – A gray-walled nursery in a Maryland home is crowded with cards, Mylar balloons and toys marking milestones Sebastien Cabness never reached.

A stuffed giraffe wears a hat from a party held on what would have been his first birthday.

An Easter basket with his name bulges with untouched candy.

On a child’s rocking chair, a hippo with a tag begging “squeeze me” sits next to a book titled “I Prayed for You.”

“This baby was very much wanted,” Audri Cabness said of her son. “He was not some throwaway baby.”

When her son died in a Washington hospital three days after he was born, Cabness knew nothing about the statistics stacked against her or him. Only later did she learn that she was not alone in her grief, and that it was for a disturbing reason: The nation’s capital is one of the worst places to be a pregnant black woman.

In a nation that fails women and children more than any other wealthy country, as measured by maternal and infant mortality rates, black women and children carry a significantly bigger burden of that loss. And that disparity is even starker in Washington, according to advocates and health data.

It would be easy to dismiss this as an issue of economics or education. It also would be a relief to policymakers because that would make it a simpler problem to tackle. But studies have found that wealthy, well-educated black women and their newborns are just as vulnerable to these deaths.

Take Kyira Johnson. She spoke five languages, had her pilot’s license and was the daughter-in-law of Judge Glenda Hatchett, who has a TV show. Johnson bled out hours after a routine C-section.

Serena Williams, one of the most powerful black women in the world, also shared how she developed a blood clot in her lungs after giving birth, leading to several surgeries and uncertainty. “I am lucky to have survived,” she wrote in a piece for CNN.

Monifa Bandele, vice president of MomsRising, which has launched a Maternal Justice campaign, calls Williams “a gift.” Bandele and other advocates have been shouting and marching, trying to get lawmakers and the public to acknowledge and address the racial disparity in maternal health, and it helps that the message is now coming from a familiar face.

But it shouldn’t take a renowned athlete for us to recognize that a problem exists and that it deserves our attention. The stakes alone – which are literally life and death – should have us listening.

“When a middle-aged man goes into a hospital and says, `I have chest pains,’ it’s boom, boom, boom,” Bandele said. That man, she said, is whisked into a room and his treatment follows a checklist. “It can end up being gas, but he is seen.”

Hospitals, she said, should be forced to adopt standard protocols that would ensure every pregnant woman and newborn receives exactly the same treatment, regardless of their background. She and other maternal-health advocates are pushing for federal legislation that would help states address the issue.

“We find story after story of black women being neglected,” she said. “We kind of live in the space where we’re invisible, where black women’s bodies are invisible, but also hyper-visible in another sense. I can’t count the number of times I’ve been followed in a store, but when I need help, it’s like I’m almost not even there.”

proved funding for a “maternal mortality review committee”

To the District’s credit, the D.C. Council apin its upcoming budget, which will go into effect in October. The committee, which resulted from a bill written by council member Charles Allen (D-Ward 6), will examine the causes behind the high rate and offer recommendations.

From that, hopefully a clearer picture of what is occurring in the city will emerge. Studies have found that lifelong exposure to racism places black women at a health disadvantage even before they become pregnant, and it can contribute later to pregnancy complications and premature births.

The committee, as part of its mandate, must provide a publicly available annual report.

But here is what we already know: Nationally, black babies are more than twice as likely as white babies to die, and black women are more than three times as likely to die of pregnancy-related causes as white women.

The District’s maternal mortality rate is more than double the nation’s, and among the maternal deaths recorded between 2014 and 2016 in Washington, 75 percent were of African American women. Infants in predominantly black Southeast Washington have been found to die at nearly 10 times the rate of those in wealthier and whiter Northwest Washington.

Cabness grew up in the District attending mostly private schools and graduated from Duke Ellington School of the Arts before going to college. When she found out she was pregnant at 38, she packed up her one-bedroom apartment in the District and found a four-bedroom home in Laurel that seemed ideal for raising a child. Her mother, who has a doctorate in social work, quit her job in Florida to help her care for the baby.

Cabness was 26 weeks into her pregnancy when Sebastien was born on Nov. 5, 2016. Three days later, she held him for the first and last time as he stopped breathing.

What happened in those days can be dissected for medical mistakes and the effects of prematurity – and Cabness said she may one day file a lawsuit. An autopsy report shows Sebastien weighed 1 pound 13 ounces and had injuries that included a punctured trachea.

But beyond dispute is what happened once Cabness left the hospital, emptyarmed. She placed Sebastien’s ashes in an urn in his room, which she visits at the same time every day, and she has spent the nearly two years since questioning every detail leading up to his loss, down to the color of her hair when he was born.

A color specialist, she had dyed it pink because she knew if she went into early labor she might have to spend weeks in the hospital, and she thought the bright hue might provide a cheerful distraction. But now, she chastises herself for it.

“I think the pink hair, being a black woman, a single mother, being on Medicaid, there was a certain perception,” she said. “They didn’t know I had two degrees.

They didn’t know I owned two salons.”

There is no way, of course, to draw a definitive line between Cabness’s loss and her race, not without experts studying her case in detail. But Cabness believes it played a role in her son’s not getting the best care and her not getting clear answers once he was gone.

She also knows that in Washington, she is not alone in that sentiment.

In private moments, Cabness pulls a plastic bag from her son’s nursery closet, places her face to it and breathes in the fading scent that remains on the clothes he last wore. But in other moments, she exchanges messages of solidarity with strangers who also lost babies they barely had time to hold. After Cabness wrote about her experience on social media, she started hearing from other black women in the area.

One woman described how movements in her child’s stomach were dismissed as gas. By the time it was discovered that the baby’s intestines had ruptured, it was too late.

Another woman wrote about how she waited three hours to get treated for high blood pressure associated with preeclampsia. When she finally received medication, it was too strong for her baby’s lungs.

Cabness said she knows that by sharing her grief so publicly, people will see her as unable to move beyond her son’s death. But she said that is not why she is talking. It is not just about Sebastien, or her.

It is about the next black woman who will go into labor in the city. It is about the next nursery that will feel too empty no matter how much it is filled.

No Comment