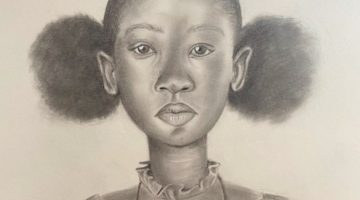

MIAMI — Public officials, ministers and the community came together to take a stand against violence at events in the Miami neighborhoods of Liberty City and Overtown in recent days. At the Sherdavia Jenkins Peace Park in Liberty City, 108 white balloons were released in memory of children who were killed in Miami-Dade County during the lifetime of 9-year-old Sherdavia.

MIAMI — Public officials, ministers and the community came together to take a stand against violence at events in the Miami neighborhoods of Liberty City and Overtown in recent days. At the Sherdavia Jenkins Peace Park in Liberty City, 108 white balloons were released in memory of children who were killed in Miami-Dade County during the lifetime of 9-year-old Sherdavia.

She was killed by a stray bullet in 2006 during a confrontation between adult men as she played in front of her home.

The Liberty City “village” united to reflect on Sherdavia and other youth who died from gun violence and also to discuss and pray for a better community in which they won’t suffer from what organizers called senseless violence.

“The peace park was built as a symbol for our children to know that they are safe in our dear Liberty City. Unfortunately, there are those who don’t want that to become a reality,” Miami City Commissioner Keon Hardemon told the gathering at the observance July 1 at the park located at Northwest 62nd Street and 12th Avenue.

“This must be the end of senseless shootings in our community,” Hardemon said. “It is time for us to make a significant and meaningful difference in our community and any time you pass Sherdavia Jenkins Park, let it be a reminder of the task that we have ahead of us.”

Organizers included The Kuumba Artists Collective, headed by artist Dinizulu Gene Tinnie – which spearheaded the drive to erect the memorial – as well as the Jenkins family, the Liberty City Community Revitalization Trust, the Multi-Ethnic Youth Group Association (MEYGA), the Miami Children’s Initiative and the Belafonte TACOLCY Center.

Torina Holmes, 15, a participant of MEYGA’s summer camp, recited an original poem in honor of Sherdavia: “Born to be strong, that’s me/ Always be known, that’s me/ Living in the heaven’s gates; that’s me/ Sherdavia Jenkins, that’s me.”

In another event, the RJT Foundation Inc. observed its second anniversary of working toward ending what it calls the cycle of violence and helping the families of murdered children. The event took place at Barbara Carey Shuler Manor June 28.

RJT represents the initials of Roman Bradley, JaQuevin Myles and Trevin Reddick, sons of the founders, who were best friends since elementary school and died from gun violence within two years of one another.

Roman Bradley was the son of Denise Brown, founder and CEO of the foundation, which has grown from being a support system for one family to include more than 35 families, according to Brown.

Its services include grief support workshops for parents, siblings and significant others of gun victims, care packages for siblings and dependents, assistance toward funeral expenses and a Reading Warriors program for the youth.

Sharron Ladson, whose pregnant daughter Angelese was killed in a drive-by shooting two years ago, testified as to the help she and her family have received from RJT.

“Angelese was snatched out of our lives, leaving a grieving 6-year-old daughter and an 11-year-old nephew who she practically raised by herself,” Ladson said. “I can honestly say this foundation has helped us and helped them to turn their frowns into smiles. As well, it has assisted me personally and encouraged me to endure when I needed it most.”

RJT’s Reading Warriors program has enrolled 21 children. It was created to promote love and education to children under 18 who lost a parent or other loved ones to violence. The participants took part in an eight-week program recently.

“We wanted to find ways that we could tackle the youth in hopes that when they’re older they don’t become a perpetrator or a victim themselves,” Brown said. “When they’re more educated, they’re less likely to commit violent acts of crime.”

Brown said RJT has had problems securing grants and continues to seek funding. The group is also trying to win over more supporters, sponsors and contributors. Brown said donations do not have to be limited to money.

“It could be whatever you’re skillful in,” she said. “Sharing your talents and resources, that’s another way of giving back. If you truly want to make a difference in the community, then try to help reduce the level of violence.”

Brown, who was motivated to start the program after her 20-year-old son was fatally shot in 2012, said the mothers in RJT like to think of themselves as survivors.

“When it happens to people, they feel hopeless [and] all alone, like nobody really understands their true feelings, their pain,” Brown said. “By us being that support system for them, we can honestly say we can identify because a majority of the people that work with the organization have been [through it] at one point.”

No Comment