By ALVA JAMES-JOHNSON

The Columbus Ledger-Enquirer

COLUMBUS, Ga. — Tony Watkins has fond memories of spending time with his great-grandmother in Lowndes County, Alabama.

Mary E. Russell Watkins, affectionately called “Ma’dear” by her children and grandchildren, owned 40 acres where she raised livestock and planted her own vegetables.

Watkins, who grew up in Columbus, Georgia, spent several years helping Ma’dear on the Alabama farm. And in 2009, she asked him to clean an old mill shack at the bottom of the hill. That’s when Watkins made a startling discovery that changed his life.

Buried under the house was a pair of iron shackles that had been used to chain slaves. One of the links had a cut two-thirds into the metal, which indicated an attempt to escape.

When Watkins asked Ma’dear what the shackles had been used for, she said, “Boy, just go back and bury them.” And that only made him more curious.

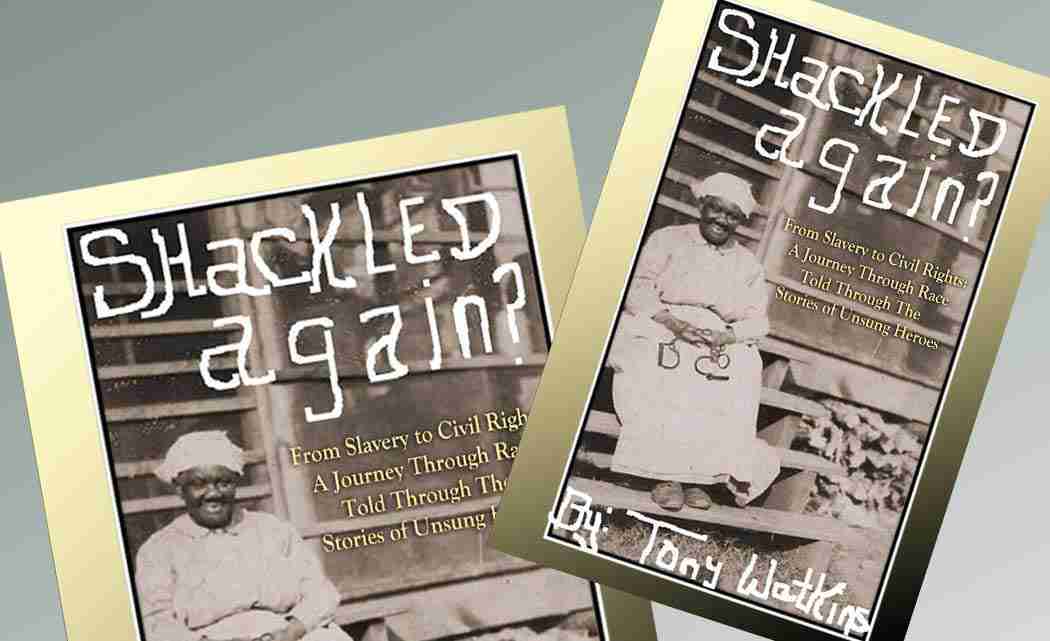

Now Watkins, 44, is the author of a book titled, ”Shackled Again?” The book recounts that experience and other stories along with historic documents, photos and personal accounts that he has collected while digging deeper into black history. On the cover of the book is a black-and-white photo of his great-grandmother’s aunt, Martha Washington, taken in 1911.

In the book, Watkins argues that many black Americans are still shackled because they don’t know their history and remain trapped in a cycle of socio-economic despair.

“When I was coming up I knew about Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass,” said Watkins, a Montgomery resident who left Columbus after finishing his junior year at Spencer High in 1989. “But I didn’t know anything about the Freedom Riders; I didn’t know anything about the foot soldiers, the ones that had to keep their mouths closed, or the people that were lynched.”

Watkins said his family moved to Columbus from Fort Stewart, Ga., near Savannah when he was 10 years old, and lived at Fort Benning until he was in the 11th grade.

His family still lives in Columbus. But when Ma’dear started aging, he went to help her take care of her property. He said he had lived with her as a little boy and always considered the farm home. Still, it was a major adjustment living outside Fort Benning.

“Before that I didn’t really experience racism because on base you had a melting pot of all of these races,” he said. “Then when I went to Bama, as I call it, and you had three lines — you had a black line, a white line and a church line and those lines never crossed each other, even in 1989.”

Watkins said Ma’dear worked for a white family as housekeeper, and it was almost like she just accepted her place, even in that era. He said she had inherited the 40 acres from her husband’s family and was also very independent.

Watkins said Ma’dear told him stories about her grandmother, Rosanna Jefferson, who was born a slave in 1856 on the Jefferson Plantation in South Carolina. But the information was sketchy, he said.

Watkins said his great-grandmother came from a generation that didn’t dwell on the past or show much emotion.

Once they were at a funeral and he asked her why she didn’t cry.

“‘Boy, if you cry one time, you’ll always cry,”’ she said.

Ma’dear died in January 2014 at age 95.

“She lived a great life and I can tell you one thing about her, she was a warrior,” he said. “She was a warrior who raised 11 children by herself, her grands and her great-grands. She had enough love to go around.”

Watkins regrets that he didn’t learn more about his family history before she died.

Now he’s on a mission to collect as much black history as possible before others of her generation pass on.

In his book, he tells the stories of unsung heroes who participated in various civil rights events, including the 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, now known as “Blood Sunday.”

Two people featured in the book are the Rev. Fredrick Douglass Reese, who wrote the letter to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. inviting him to Selma, Alabama; and Joanne Bland, who participated in the march as a child. Bland had experienced the pain of segregation when her mother died in the hallway of a Selma hospital because there was no colored blood” available.

“By age 11, I was marching in protest movements,” Bland is quoted as saying in the book. “I remember what it felt like to kneel and pray on the front steps of the Dallas County Courthouse. Even though I was not old enough to register to vote, I still liked being a part of the action. We were taught to ask God to ‘lift the hearts of those evil men who would not let our parents vote.”’

A chapter in the book deals with the lynching of black mothers in segregated communities.

“I always heard about the black men that were lynched, but I never heard about the black women,” Watkins said. “And those stories are very important to us because black women were beaten, raped and even lynched trying to protect their own families. These are stories that we need to know, not only as a black community, but as a community, because as ugly as the history is, it has to be told.”

Watkins said the book, which is self-published, is now available at Barnes & Noble college campus locations and also can be purchased on Amazon.

He said the book is selling well due to articles that have run in newspapers across the country, the anniversaries of events like “Bloody Sunday” and a renewed interest in black history by many in the community.

Watkins said he wrote the book while working two jobs — one as an administrator with the Alabama Department of Transportation and part time as a meat and seafood clerk at the Fresh Market.

Watkins is now working on a sequel that will include interviews with former Secretary of State Gen. Colin Powell; Ambassador Andrew Young; and comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory.

Others in the book will include Moses J. Newson, a journalist who covered the murder of Emmett Till; Diane Nash, a leader and strategist of the student wing of the civil rights movement; and white freedom riders. One man he interviewed is 108 years old.

“When you hear these people dying out, ‘It’s almost like, man, I can’t lose another one,”’ Watkins said. “Everyone has a story to tell and everyone has a history.”

He said there’s much that people in today’s black community can learn from their ancestors.

“I think if we go back to that community setting, to where we can talk to each other, and work with each other and help each other, then we can actually become a great community,” he said.

“What we have to do is work on our community, because if we can’t work with our own people, what makes you think we can work with anyone else?”

No Comment