Acknowledging slavery and its legacy is first step towards reparations

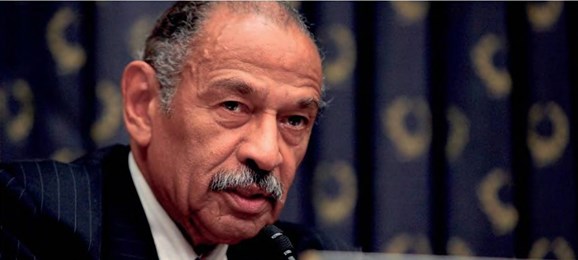

Thirty years ago, Rep. John Conyers Jr. introduced a bill in the House of Representatives calling for a commission on slavery reparations but it got nowhere. The Michigan Democrat Conyers introduced it every year

until he retired in 2017. On June 19, House Resolution 40, the “Commission to Study and Develop Reparations Proposals for African Americans Act,”finally made it to the House floor, sponsored now by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas.

The writer Ta-nehisi Coates is credited with generating the new interest with a 2014 article in The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations,” but it still took five years for Congress to formally take it up. Fox News cited polls showing only between 21 and 32 percent of Americans support reparations, which is no surprise; even Barack Obama declined to make it part of his presidential agenda, telling Coates in an interview that paying reparations would be “impractical.” Obama rebuffed calls to use executive action to create the commission sought by Conyers, The New York Times reported.

In any case, there is little chance that the bill would become law because Republicans, who overwhelmingly oppose it, control the Senate and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has commented, “I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us living are responsible are a good idea.”

Probably the main stumbling block is that the debate has understandably centered mostly on financial reparations. Gen. William T. Sherman in 1865 promised 40 acres and a mule to every freed slave. Congress approved the offer and, The New York Times, noted, 40,000 former slaves began planting and building on the land. But President Andrew Johnson voided the Sherman order and returned the land to the original owners. Analysts have come up with wildly differing amounts for any payout, ranging from $71.08 per person to $80,000 per person, the latter amount totaling $2.6 trillion for the 30 million African Americans who are eligible, based on the worth of the 40 acres in today’s dollars, according to Duke University economics professor William A. Darity Jr.

The legacy of slavery is directly responsible for the vast economic disparity between African Americans and whites. Still, the idea of paying out money to one segment of the nation, even if to compensate for the atrocities of the past, appears to be the stumbling block even for some African Americans. Burgess Owens, a University of Miami graduate and a former NFL player, told the Congressional hearing that reparations would be an insult.

But it is not only African Americans who are demanding compensation for slavery. As this column noted a year ago, Caribbean nations are demanding reparations from Britain, France and the Netherlands, with the English-speaking countries suing Britain, noting that, after slavery ended in the colonies, the British government paid “reparations” totaling more than $200 billion in today’s currency – not to the freed slaves but to their former slaveowners. The African World Reparations and Repatriation Truth Commission is demanding $777 trillion as compensation to the continent. And there is precedent for reparations in the United States. In 1988, the federal government paid $20,000 each to 80,000 Japanese American who were interned during World War II and apologized – which it has not yet done to African Americans.

Still, reparations do not have to mean sending out checks. Reporting on the Congressional hearing, New York Times reporter Sheryl Gay Stolberg noted that some speakers raised alternatives such as, in her words, “zero interest loans for prospective black homeowners, free college tuition, community development plans to spur the growth of black-owned businesses in black neighborhoods… [to] address the social and economic fallout of slavery and racially discriminatory policies that have resulted in a huge wealth gap between white and black people.”

That may be the focus of the debate. The greatest financial legacy of slavery is that while whites were able to accumulate capital and collateral to get ahead in life, African Americans entered the post-slavery era with nothing, their descendants affected even in the amount of benefits from programs such as Social Security.

Resistance to reparations, though, comes from the fact that, more than 150 years after slavery ended, the United States has not come to terms with its 246-year history of enslaving millions of human beings. “Comparisons are odious,” as the Englishman John Lydgate said around 1440, but sometimes they can help prove a point. In this case, why does the word “slavery” not evoke the same visceral response as, say, “Holocaust”? It may be that many Americans, including African Americans, want to forget that chapter in their history. Jews, though, are rightly insisting that the world must not be allowed to forget Hitler’s gas chambers.

In fact, the reparations issue is impacting national consciousness even as some descendants of the slave owners are pushing for recognition of their history. So, even in the unlikely event that trillions of dollars is paid out in compensation, that will not bring about the longdelayed national healing and reconciliation. The horror of the past still haunts the American character and those who do not know what the fuss is all about should read “The War Before The War” by Andrew Delbanco.

No Comment