By LINDA ROBERTSON

Miami Herald

MIAMI — Motley Miami slithers daily through Courtroom 6-6, where bailiff Tony Nathan and Judge Ed Newman hear the pleas of prostitutes, drunk drivers, petty thieves, probation violators, barroom brawlers and pot pushers.

They recall the antics of a repeat offender who used to post YouTube videos on how to beat a suspended-license rap by acting delusional in court. He would hide a tape recorder in his pocket, take the stand and start yammering.

“This cat would feign craziness in order to get a psych evaluation,” Nathan said. “But Ed and I caught on. I had to search him. I told him, ‘I know your game, my brother, and I don’t want to be on your YouTube video.’ “

The bad driver and bad actor got so disruptive he was held in contempt and sent to jail, a radical response by Newman and Nathan, who are masters at defusing tempers and persuading most of the people who come through Courtroom 6-6 to never come back.

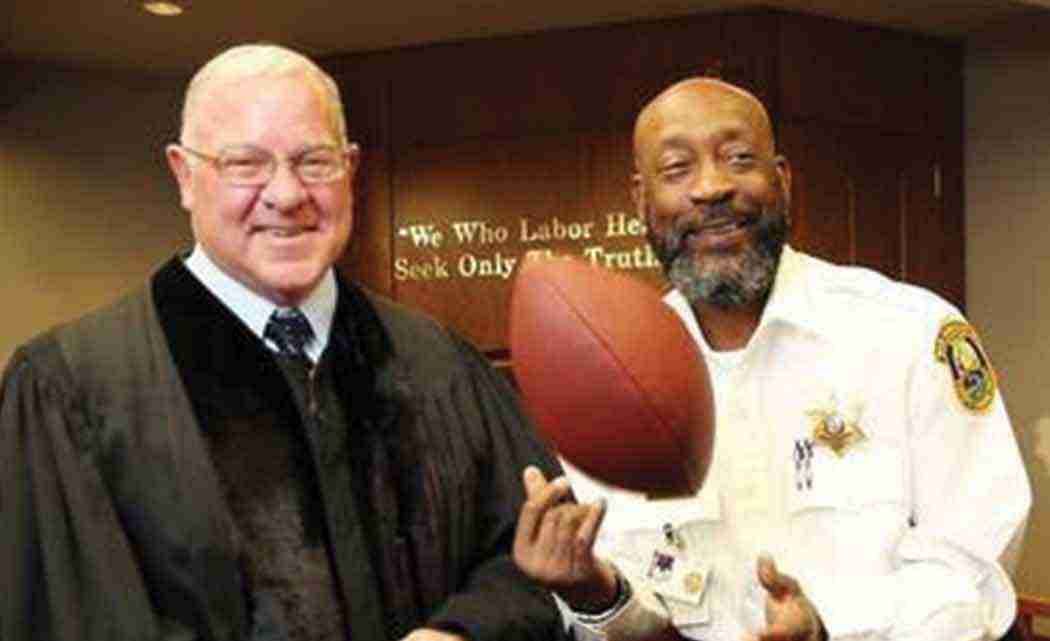

“We make a good team,” Newman said – just as they did in six seasons together from 1979 through 1984 with the Miami Dolphins, Newman as the burly guard blasting holes for Nathan, the elusive running back with more moves than James Brown. Newman wears his Super Bowl ring from the 1973 season. Nathan and Newman were on two Super Bowl teams together under Don Shula.

Fans remember. One recent morning jurors asked to pose for pictures with Newman in his black robe and Nathan in his gold badge. They got autographs, too. It was a brief break in county courthouse action at the bustling justice factory Newman calls “the funnel.”

Nathan, a more reluctant celebrity than his boss, finds himself back in the spotlight now with the release of Woodlawn, a feature film based on the true story of Nathan’s high school football team in Birmingham, Alabama.

“It brought tears to my eyes,” Nathan, 58, said of the red-carpet premiere he attended in his hometown on Oct. 15.

The young “Touchdown Tony” – the nickname he earned for his prolific scoring _ is a key character in the movie, set 40 years ago in a community wracked by the vestiges of Jim Crow segregation.

The unexpected success of Nathan’s Woodlawn High team in 1974 unified the student body and a city notorious for the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church by Ku Klux Klansmen that killed four black girls.

During Nathan’s childhood, the Old South gave grudging way to the New South. He was a boy when Birmingham police turned dogs and fire hoses on student protesters, when Martin Luther King Jr. was jailed for leading sit-ins at lunch counters, when Gov. George Wallace proclaimed “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” and blocked a doorway at the University of Alabama where two black students were trying to enroll.

“Village Creek was the border separating my black neighborhood from a white neighborhood, and if the white kids caught the black kids swimming in their side of the creek, they’d throw rocks at them, and vice versa,” Nathan said. “Birmingham was at the center of the civil rights struggle, but my parents tried to shield us from the ugliness. When we were faced with racism, they were very strict about making us follow the Golden Rule.”

Nathan’s father, William, was a mechanic at the Connor Steel mill, and was known in the neighborhood as “Coon Man” because he was an avid raccoon hunter. His mother, Louise, was a seamstress who made her children’s clothes. Nathan spent summers working at his grandfather’s farm. Church, chores, school and sports were the pillars of Nathan’s life.

Nathan’s parents and older sister warned him that he would be treated like an unwelcome guest at Woodlawn High, which was among the last of Birmingham’s schools to integrate, in 1965.

When Nathan started as a freshman in 1971, police officers with dogs were stationed in the hallways. Fights between black and white students were so common that the school was almost shut down. Blacks sat on one side of the classrooms and whites on the other, with a row of empty seats separating them.

Clubs, student government, the cheerleading squad and most sports teams were still all-white. When Tandy Gerelds became varsity football coach, the team was finally integrated with five black players. Nathan was a ninth-grader, and he joined the junior varsity team with trepidation. Initially, Gerelds had a hard time getting black athletes to play because they were treated like traitors by their own friends.

“The vibe at Woodlawn was a volatile one of racial strife,” said Nathan’s teammate Reginald Greene. “Lots of confrontations, protests, boycotts. A more militant black attitude had emerged because of Angela Davis, Bobby Seale, Huey Newton and Muhammad Ali. We wore big Afros, sandals and dark sunglasses. Many young African Americans had distanced themselves from King’s way, and if a white person hit you, you hit back.”

Because of his upbringing in a compassionate household and his humble personality, Nathan was a peacemaker.

In August 1973, a remarkable transformation occurred to bind together whites and blacks on the fractious football team, one which players refer to today as “a miracle,” and which is the basis of the movie, directed by the sons of former team chaplain Hank Erwin.

Gerelds held a five-day preseason training camp at school, requiring players to sleep in the sweltering gym. Each night he hosted a motivational speaker. One of them was local evangelist Wales Goebel, who gave a riveting talk about surviving a flaming car crash and becoming sober through “the grace of God.” He asked the players to seek salvation, and they climbed down from the bleachers to the gym floor to kneel with him – an emotional scene recreated in the movie. Nathan made the commitment, although he doesn’t remember it.

“I had a concussion the whole week,” he said.

The Nov. 8 showdown between Woodlawn and No. 1-ranked Banks was billed as Nathan vs. Jeff Rutledge, the Banks quarterback who would be Nathan’s teammate at Alabama. Before the game, Nathan, Rutledge and their teammates met at a local swimming pool and at a Fellowship of Christian Athletes gathering to share their religious commitment.

“As athletes we had a platform,” Rutledge said. “This revival of Christianity and tolerance got the whole city excited.”

A record crowd of 42,000 watched Banks beat Woodlawn, 18-7. Nathan ran for 112 yards and a touchdown. Rutledge threw for 185 yards and a touchdown. For Woodlawn, the disappointment was mitigated by the feeling that a more profound kind of history had been made that season.

A month later, Nathan signed with Alabama, after coach Bear Bryant had visited and ate a dinner of roasted raccoon.

In the movie, Bryant, played by Jon Voight, promises Nathan he’ll recruit more black players because “it’s time.”

At Alabama, Bryant allowed Nathan to refuse to pose for a photo with Gov. Wallace. Rutledge ran the wishbone offense, with Nathan running, catching and blocking out of the backfield as “the most unselfish guy I played with,” Rutledge said. The Crimson Tide won the national title their senior year.

“I think Tony would have won the Heisman Trophy with more carries at USC or Ohio State, but he chose Alabama because he was a true team player,” Greene said.

Nathan was picked in the third round of the 1979 NFL Draft by the Dolphins, married high school sweetheart Johnnie and moved to Miami, where he lives in the same house today.

As a Dolphin, he set all-purpose yardage records and befriended Newman, an intellectual offensive lineman who took University of Miami law school classes at night.

“We used to ask Ed to stop asking so many questions at team meetings so we could get out,” Nathan said.

Both became All-Pros – Nathan as a rookie returner, Newman as a guard – and were inducted into the Dolphins Walk of Fame in 2014.

After assistant coaching stints with the Dolphins and three other NFL teams, followed by FIU and high school coaching jobs, Nathan was pondering his next move when Newman offered him the bailiff post.

“You meet all different personalities with all kinds of problems and they don’t want to be here,” Nathan said. “Judge Newman and I try to reach them. Like a football player who just wants to freelance and do it his way, you’ve got to explain how to conform to the rules. You tell them, ‘Please let this be the last time I see you.’ “

Newman said he’s never had to use the panic button on his bench and Nathan has never had to use his pepper spray.

“We get manipulators, the anxious, the bold, the riffraff, the addicted, the depressed,” Newman said. “Tony and I have radar-like communication. We’re not sadistic. We’re fair. Sometimes I’ll use a Shula metaphor to deliver a message.”

The Brooklyn-born Newman, 64, has been a county court judge for 21 years, handling an average of 35 misdemeanor cases per day. He favors second chances and firm words of guidance. He sees himself and Nathan as “teachers, not executioners or torturers.” Newman dispenses justice with a velvet gavel, ordering community service, counseling and extended payment plans for fines when jail time can be avoided.

“Most people are redeemable,” he said. “The worst thing a judge can do is get jaded. The underlying philosophy is that I’m a doctor of society preparing the right prescription.”

Aiding Newman in that trying but noble task is Nathan, still the humble peacemaker using the lessons he learned at Woodlawn.

“You get a soft spot in your heart for people,” Nathan said. “I’ve met some very angry folks. I just talk to them: ‘Can you calm down, man? How can we fix this situation?’

“When I was young, I developed faith in people. I’ve never lost it.”

No Comment