Orlando, Fla. (AP) – University of Florida administrators told faculty members they couldn’t used the words “critical” and “race” together in describing a new concentration of study, out of fear that it would antagonize state lawmakers who are contemplating a bill to ban critical race theory in state government, according to a grievance filed by the faculty union last week.

During a meeting with College of Education faculty in October, an administrator relayed that the graduate school wouldn’t approve anything with the word “critical” in the title of a curriculum initiative to examine race and anti-racism.

Faculty members concluded that the administration was asking the college “to change the name of a proposed concentration titled `Critical Study of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Education,’ presumably to a title less offensive to the Florida legislature,” said the complaint filed by Christopher Busey, an associate professor, who said he was threatened with discipline if he used the words “critical race” in his curriculum design.

The grievance is seeking to stop the university’s attempt “to eliminate and/or whitewash” critical race theory from the curriculum.

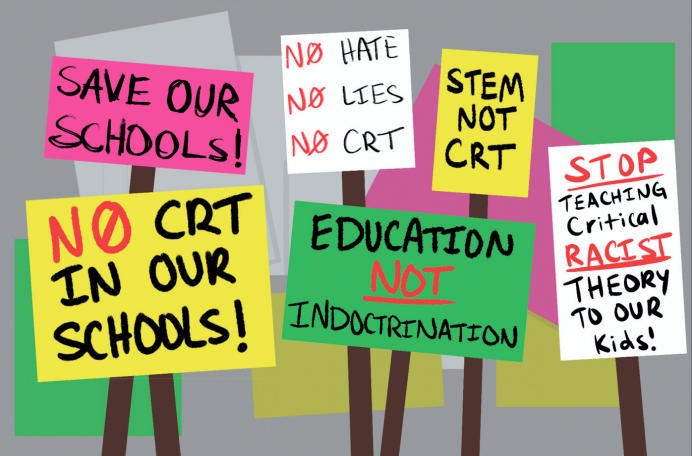

The theory is a framework legal scholars developed in the 1970s and 1980s that centers on the view that racism is systemic in the nation’s institutions and serves to maintain the dominance of whites in society. Many conservatives object to critical race theory, especially in grade school education. They argue it is a divisive ideology because it partitions society into oppressors and oppressed based on their race, and see it as a form of neo-Marxism derived from critical theory.

Administrators told College of Education faculty members they would support a title that says “`studies of race’ but not critical studies of race,” the complaint said. “The requirement that faculty eliminate `critical race’ from their curriculum under threat of discipline discriminates against faculty on the basis of the content of the material.”

The brouhaha over using the words “critical race” is the latest accusation in recent months of University of Florida administrators curbing academic freedom in order to appease Florida politicians. The university in October prohibited three professors from testifying in a lawsuit challenging a new election law that critics believe restricts voting rights. A school official said that such testimony would put the school in conflict with the administration of Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, which pushed the election law. The university reversed that decision last month.

Facing criticism, University of Florida President Kent Fuchs set up an independent task force to study the issue and accepted its recommendations affirming free speech and academic freedom, as well as that there would be a presumption that requests by faculty to provide expert testimony will be granted.

In a response to an inquiry over the matter by an accrediting agency last week, the university said it wasn’t subject to external influences when making the decisions on the professors’ testifying, including from the school’s Board of Trustees. More than half of the university’s trustees are appointed by the governor.

“These actions were not affected by entities or individuals outside of the university’s established governing system,” the university said.

The tension between College of Education faculty and university administrators had been brewing for months, with administrators from the Provost’s Office having discussions with the professors about two recent bills from the Florida Legislature, the complaint said.

The first bill, which was signed into law by DeSantis last summer, requires state universities to conduct yearly assessments on whether there is “viewpoint diversity” and intellectual freedom at their schools. The second bill, introduced in September by a Republican lawmaker from the Space Coast, would ban the use of critical race theory at all levels of Florida government.

In September, Associate Provost Chris Hass met with faculty members to discuss curriculum initiatives on race and antiracism that had “drawn the attention of university officials.” Hass told the faculty members that the college was viewed favorably by the state and that administrators were recommending “avoiding any issue that might jeopardize the relationship,” the complaint said.

In a statement, after being provided Busey’s complaint and supporting documents by The Associated Press, the university said any grievance is confidential and the school was unable to publicly acknowledge whether one has been filed. “However, the information in the documents you provided contains a number of inaccuracies, and we will address them through the appropriate processes,” the statement said.

No Comment