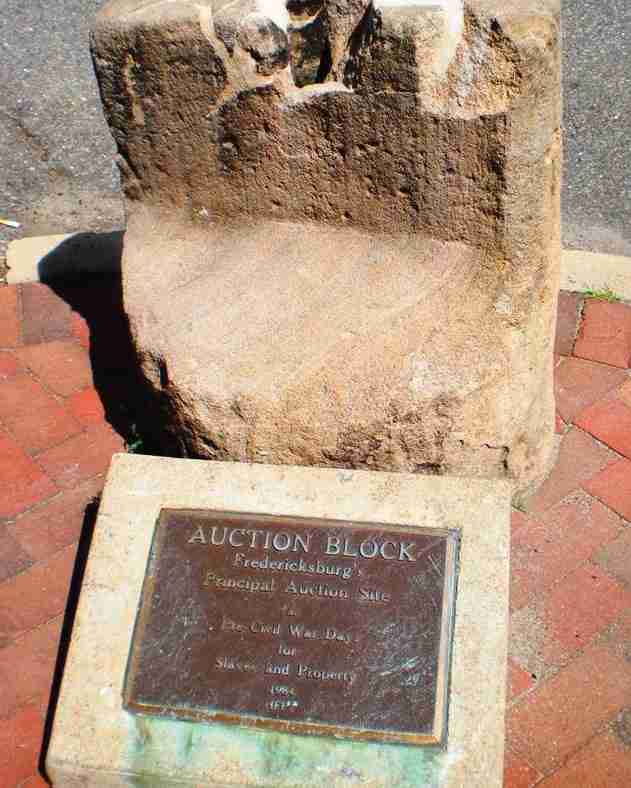

Fredericksburg, Va. (AP) – Fredericksburg’s slave auction block is bigger than many people knew.

When it sat at the corner of William and Charles streets, its former location for more than 170 years, a significant portion of it was underground. N. ow installed in a ground floor gallery at the Fredericksburg Area Museum, its true size is apparent, all 1,000 pounds of it.

But the single chunk of Aquia sandstone carries even more weight than that.

“The foundation of this exhibit is for people to understand the historical and emotional weight of the block,” said Gaila Sims, FAM’s new curator of African American history and special projects. ings.”

“It is imbued with our feel“A Monumental Weight” is the name of the new exhibit featuring the auction block that recently opened.

The block was on public display at the museum during the fall in 2020, several months after it was removed from its former location. At that time, it was blocked from being immediately visible by a partition.

Sims said that was because museum staff were worried about the profanity that was spray-painted on the block when it became a focus of the social justice protests that occurred after George Floyd’s murder.

But Sims said all the conversations with community members she’s had and all the volumes of reading she’s done since starting in her position this past August led her to the conclusion that “people wanted the space to be more open.”

In addition to reading and talking, Sims said she spent lots of time standing alone before the block, thinking, “How can we make this space what people want and need?”

For the new exhibit, the partition has been removed and the block is in the open. Panels immediately surrounding it tell the story of its early history and what is known about the people who were bought and sold there, as well as about the domestic slave trade in Virginia, which after the 1808 abolishment of the international slave trade, became Virginia’s largest industry.

Additional panels will describe the series of community conversations that took place from 2017 to 2019 and led to City Council’s vote to move the block from its original location and the events of the summer of 2020, when the block became a symbol of racial oppression during the downtown Black Lives Matter protests.

Another wall of the gallery explores the auction block’s emotional weight by presenting historical descriptions, first-person reflections, social media posts and news reports about the auction block over the years.

That part of the exhibit is “a living archive,” Sims said. Visitors to the exhibit are invited to write down their own reflections and can choose to have those reflections added to the wall, she said.

Visitors can also write their reflections in a notebook or submit them online via a QR code.

The reflection space will also acknowledge everyone who helped Sims and the rest of the FAM staff develop the exhibit.

“It’s important for people to know that we didn’t just decide what would go here on our own,” Sims said.

Sims said she thinks it’s important that the community members can now choose whether or not they want to see the auction block.

For some people, it had become such a part of the landscape of downtown that they didn’t really see it anymore, while for others, “it was devastating every time they encountered it,” she said.

And because history is evolving and never static, “If what is here doesn’t work, we can change it,” Sims said.

An accompanying digital exhibit on FAM’s website will expand on the inperson exhibit, providing “deeper contextualization of the block’s history, Virginia’s relationship to the market in enslaved people, and enslaved people’s experiences of being bought and sold,” according to a press release about the exhibit.

Sims will present a series of free public presentations on the auction block in January and February, when the museum is closed.

No Comment