The U.S. Supreme Court heard five hours of testimony recently on affirmative action lawsuits against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina (UNC). Based on the comments of some conservative justices, observers are predicting that the court will deem it unconstitutional for colleges to consider race as part of their admissions criteria. That would be a grievous mistake.

Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Clarence Thomas are implacably opposed, along with Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. They will very likely be joined by the other three conservatives – Amy Coney Barrett, Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh, all appointed by then President Donald J. Trump – to rule in favor of the plaintiffs.

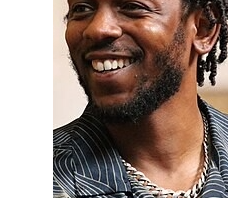

Given his background, it would not be unreasonable to expect that Thomas, whom President George W. Bush appointed in 1991, would not only support affirmative action but also strive mightily to persuade at least one other conservative to join him, making for a majority to uphold it. Instead, he is striving mightily to eliminate it.

Thomas, who succeeded the late Thurgood Marshall, the first African American justice and a stalwart defender of civil rights, owes his entire career to affirmative action. “As an undergraduate at Holy Cross College, Thomas received a scholarship set aside for racial minorities,” Creators Syndicate columnists Jeff Cohen and Norman Solomon wrote in 1995. “He was admitted to Yale Law School in 1971 as part of an aggressive (and successful) affirmative-action program with a clear goal: 10 percent minority enrollment. Yale offered him generous financial aid.”

Thomas admitted as much in a 1983 speech to the staff of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which he then chaired, deeming affirmative action "critical to minorities and women in this society." He added that, if not for affirmative action, “God only knows where I would be today. These laws and their proper application are all that stand between the first 17 years of my life and the second 17 years."

Cohen and Solomon were commenting on the fact that, despite such a history, Thomas once cast the deciding vote to weaken affirmative action and “went beyond even fellow conservatives on the bench: he argued for an immediate end to affirmative action.”

They added, “Since the early 1980s, Thomas’ career soared, thanks to a perverse form of racial preference. It was his race, as Thomas has admitted, that got him two civil-rights posts in the Reagan White House; the jobs came because he opposed the civil-rights movement. So did his boss, President Ronald Reagan, whose opposition dated back to the years of Martin Luther King Jr.”

Ketanji Brown Jackson, the other African American justice, is expected to reject this latest challenge to justifiable racial preference, which is one with a twist.

Affirmative action was originally associated with labor, dating back to the early 20th century, Smithsonian Magazine has pointed out. It was intended “to literally act affirmatively – not allowing events to run their course but rather having the government (or employers) take an active role in treating employees fairly.” It eventually expanded to education, sparking controversy over whether setting aside university admission slots to diversify the student population violates the U.S. constitution.

The Supreme Court has issued a variety of rulings on affirmative action starting in 1969 but has so far not banned it outright. The court ruled 5-4 in 1978, in a case brought by a European American against the University of California School of Medicine, “that while quotas violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, race could be used as a factor in applications to promote diversity in education,” as the Smithsonian put it.

However, opponents have never stopped insisting that “set asides” entail “reverse discrimination,” initially against European Americans, even though racial discrimination against African Americans has existed for as long as the universities have been functioning. That is so especially with the “legacy” admissions giving preference to children of alumni, mostly European Americans.

Indeed, adopting affirmative action could be interpreted as tacit acknowledgement that universities not only discriminated in the past but also that some of them profited from owning slaves. In fact, beginning in 1831, laws banned enslaved Africans from even learning or being taught to read or write on pain of horrible punishment. It was not until 1962 that the first African American, James Howard Meredith, was admitted to an all-European American college, the University of Mississippi.

The latest lawsuits are part of a sustained vendetta of a wealthy European American, Edward Blum, who, according to The Washington Post, spends time in his Maine study “scrolling the internet and looking for someone to sue.” Blum was behind the 2013 case in which the Supreme Court gutted the 1965 Voting Rights Act. His effort to have racial preference outlawed at the University of Texas failed in 2016, by one vote.

The Blum-driven lawsuits against Harvard and UNC also claim reverse discrimination, but not against European Americans. They were filed eight years ago by Students for Fair Admissions (SFA), representing – here is the twist -a group of Asian Americans.

But there is more to this sustained assault on affirmative action than its constitutionality. Rather, it is part of a trend which began at least from the end of the Civil War of refusing to acknowledge racial discrimination against African Americans not only in the past but also the present and the need to effectively deal with it.

This fierce resistance to bringing African Americans fully into the wider American community led to their developing separately from European Americans, Thulani Davis argues in her book, “The Emancipation Circuit,” which writer Elias Rodrigues recently reviewed in The Nation. The enslaved who fled to the Union lines during the Civil War – legally dubbed “contraband” by slaveowning states — developed self-sufficiency out of necessity, including building institutions and relationships needed to establish and maintain whole communities. African Americans had to create a separate nation as the only means of survival.

By now, sustained initiatives should be in place to integrate them into the nation as citizens made whole. Affirmative action has been one small step in that process. Without such programs, reconciliation between the descendants of the enslaved and the enslavers will remain impossible. It is doubtful that the Supreme Court conservatives will let that bother them.

Nor will the millions of Americans who deride “wokeness,” their state of mind being, as Michael Harriot wrote in The Guardian, “nothing more than the resentment that produced the racial terrorism of Reconstruction, the pro-lynching Red Summer of 1919, and the pro-segregation states’ rights movement” – and now “a modern-day mixture of McCarthyism and white grievance.”

No Comment