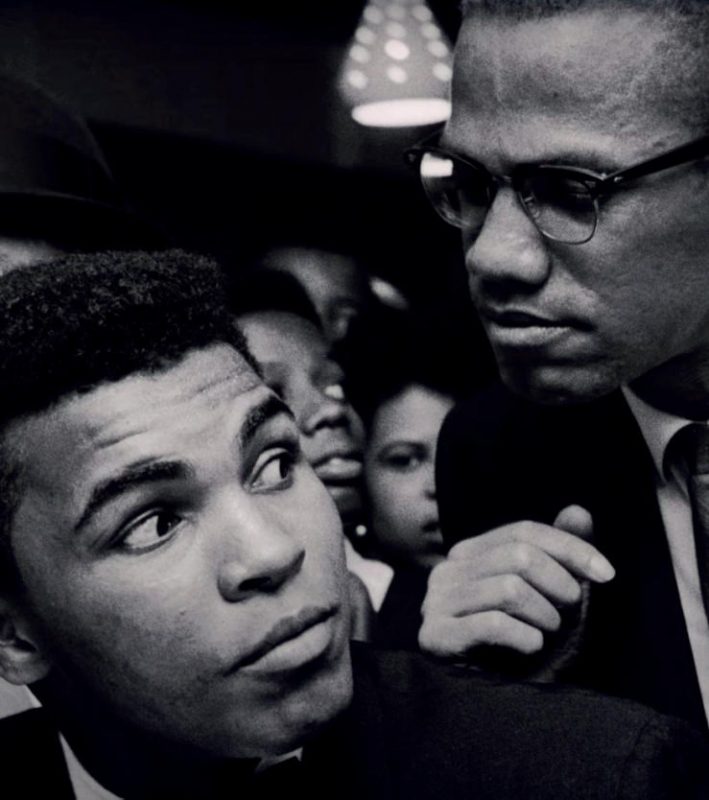

Atlanta (AP) – In the early 1960s, firebrand preacher Malcolm X and boxing phenom Cassius Clay became close friends, a fascinating relationship that fell apart and never was repaired before Malcolm X was killed by an assassin in 1965.

That relationship is explored in detail in a new Netflix documentary coming out Sept. 9 called “Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali.” The documentary by Marcus A. Clarke relies heavily on a 2016 book, also called “Blood Brothers,” co-authored by Georgia Tech associate history professor Johnny Smith and his former academic advisor Purdue University history professor Randy Roberts. Both were consultants on the film and Smith was happy with the final result.

“Being able to participate and tell the story though a different medium was fascinating and fun,” said Smith in an interview with The Atlanta JournalConstitution.

He said he and Roberts spent a long time talking about possible books connected with Ali and decided to focus on this particular relationship, which hadn’t been explored to this level of detail before.

For Ali, Smith said, “this was a really fascinating period in his life as he evolved from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali. He was a man of many masks.” CONTEMPORARIES

Ali was a gold medalist for Team USA at the 1960 Rome Olympics, then became a comic braggart known as the Louisville Lip. But while he was known for spouting memorably absurd poetry to boxing writers, he had become interested in the teachings of the Nation of Islam as a way to understand where he stood as a Black man in America.

Secretly, Clay began meeting with the leaders and struck up a friendship with Nation of Islam Minister Malcolm X, who was intrigued by Clay’s fame and potential to bring more followers to the cause.

The documentary provides added perspective from figures such as civil rights activist Al Sharpton, historian and Harvard University professor Cornel West and University of Southern California professor of cinema and media studies Todd Boyd.

“Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali were the two most freest of Black men in the 20th century,” said West in the doc. “On the other hand, there’s a cross to bear. There is a tremendous cost to being a free and loving person.” “It was a moment of transition and Ali is really at the forefront of this transition, as is Malcolm,” Boyd said. “They’re changing the way the world saw the Black man.”

The doc shows Ali in the 1960s proclaiming: “I’m free to be what I wanna be and think what I wanna think.” Malcolm X boldly critiqued the dominance of white society in a way that made many Whites and even some Blacks uncomfortable. “By nature he is evil,” Malcolm X said in an archival clip, referencing the White man.

One person the documentary got to interview that Smith did not: Muhammad Ali’s younger brother Rahman Ali, who recalled Malcolm X himself. “He had that air about him,” the younger Ali said. “It was divine. The electricity that came from his body was sacred.” Smith called Ali’s brother a compelling interview and his voice and intonations evoke his brother, who lost his ability to vocalize his thoughts with the bravado of yore once Parkinson’s Disease set in.

The daughters of both men also received plenty of airtime and are passionate and eloquent.

“Having that level of intimacy on film is hard to replicate in a book,” Smith said.

In 1964, Malcolm X sharply critiqued the behavior of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad and was booted from the organization. Ali sided with Muhammad and disavowed Malcolm X.

“Some viewers will be surprised how vengeful and vindictive Ali was after Malcolm was murdered,” Smith said. “He declared him the enemy.” Only years later did Ali begin to regret the estrangement. Smith thinks the daughters of both men made him shift his thinking.

“Those young women forced him to confront part of his past,” Smith said.

Smith said the best interview he got for his book was “Captain” Sam Saxon, who ran a mosque in Miami in the early 1960s while Clay was training there for a boxing match and introduced Clay to Malcolm X. While doing research for the book seven years ago, Smith knew Saxon was still alive but was having trouble tracking him down.

By pure coincidence, Smith was flying to a friend’s wedding in Detroit and was sitting at a gate at HartsfieldJackson International Airport when he saw a man in a wheelchair wearing a glistening ring with “ALI” embossed on it. Smith quickly figured out it was Saxon.

Smith introduced himself and said, “I’ve been looking all over for you.” Saxon replied: “That’s what they call divine intervention, my brother.” CORPORATE VOICE

Saxon was there when Clay defeated Sonny Liston in Miami and decided to change his name to Ali. “He told us many stories he hadn’t told before,” Smith said.

Smith and Roberts also sifted through thousands of pages of FBI documents.

While the FBI didn’t follow Ali, they did track both Malcolm X and Muhammad so Ali would show up. For a time, he hid his relationship with the Nation of Islam, fearful it would jeopardize his chances of winning the heavyweight title.

The film and the book try to be fair to both men, revealing both their flaws and strengths, Smith said.

“It’s important we don’t whitewash or sanitize our heroes,” he said, noting how Ali was deified by the time he lit the Olympic torch at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. (Ali died in 2016.)

“By that time Ali was robbed of his greatest gift: his voice,” Smith said. “That silence was filled by corporations and Hollywood that changed the way we looked at him.”

No Comment