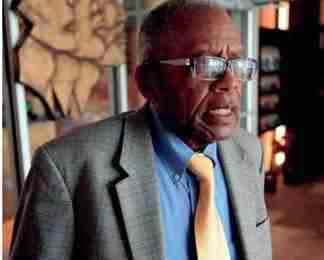

Attorney Fred Gray

By JAY REEVES

Associated Press

[Editor’s Note: Part I covered the 1932 actions of medical workers in the segregated South who withheld treatment for unsuspecting black men infected with Syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease simply so doctors could track the ravages of the horrid illness and dissect their bodies afterward. Medical workers periodically provided men with pills and tonic that made them believe they were being treated, but they weren’t. And doctors never provided them with penicillin after it became the standard treatment for syphilis in the mid-1940’s.]

THE LAWSUIT

Farmer and community leader Charlie Pollard walked into Fred Gray’s law office in Tuskegee. Gray already was a civil rights legend by that point: His clients included Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks following her arrest in Montgomery in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man.

Pollard “came into my office and asked me if I had been reading in the newspaper about the men who were involved in the syphilis tests for ‘bad blood,’” Gray wrote in a memoir.

Pollard was among the men in the study, and his visit with Gray led to the lawsuit and the multimillion-dollar settlement reached with the government on Aug. 28, 1975. In all, Gray said in an interview, government documents showed 623 men were involved in the study.

Payments to men and their heirs differed based on whether men were infected or were in the control group, whether they were dead or alive. Living participants who had syphilis got $37,500; heirs of deceased members of the control group received $5,000. Women and children who were infected with syphilis got lifetime medical and health benefits, and a handful still survive, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For decades, the study has been widely blamed for distrust among U.S. blacks toward the medical community, particularly clinical trials and other tests. In medical and public health circles, it’s known as the “Tuskegee effect.”

Freddie Lee Tyson quit the study during the 1950s after hearing rumblings that “something was wrong,” Lille Head said.

Unaffected by the disease despite years of being in the study’s syphilitic group, Tyson learned the true nature of the program only when the rest of the country found out, his daughter said. His wife and children all tested negative for syphilis, but Tyson was traumatized and feared the disease would show up somewhere in his family.

“After he found out about it he had to live with it. That could bring a person down if he wasn’t strong. He was angry and he was upset,” she said.

The lawsuit settled years before, Tyson died in 1988 at age 82 after an automobile accident. Today, the 72-year-old Head chairs Voices of our Fathers Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit organization formed in 2014 by the men’s relatives to tell the story of the victims of the Tuskegee study.

Through the decades, their loved ones have been portrayed both as unwitting victims of a horrid experiment and as ignorant hicks who brought trouble on themselves with promiscuous behavior. Many descendants are still steamed over a 1997 movie called “Miss Evers Boys,” which they believe cast the men in a bad light. A big part of the foundation’s purpose is rounding out the narrative of the men’s lives by telling the story of people like Freddie Lee Tyson, Head said.

PART III, next week

No Comment