Staff Report

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command

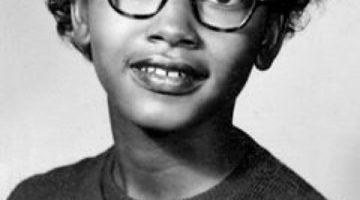

Yesterday marked the 75th Anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. In honor of those who played a historical role and/or sacrificed their lives to protect America from invasion, we highlight noted black sailor Doris “Dorie” Miller, who is credited with shooting down Japanese planes during the attack. He would die 24 years later in an unrelated attack at Liscome Bay. While alive, Miller became the first black sailor to receive the Navy Cross, the second-highest naval service honor. According to the New York Daily News, there is currently an effort to have it posthumously upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Doris Miller, known as “Dorie” to shipmates and friends, was born in Waco, Texas, on October 12, 1919, to sharecroppers Henrietta and Conery Miller. He had three brothers, one of which served in the Army during World War II. While attending Moore High School in Waco, he was a fullback on the football team. He worked on his father’s farm before enlisting in the U.S Navy as Mess Attendant, Third Class, at Dallas, Texas, on September 16, 1939, to travel and earn money for his family. He later was commended by the Secretary of the Navy, advanced to Mess Attendant, Second Class and First Class, and subsequently was promoted to Cook, Third Class.

Following training at the Naval Training Station in, Norfolk, Virginia, Miller was assigned to the ammunition ship USS Pyro (AE-1) where he served as a Mess Attendant, and on January 2, 1940 was transferred to USS West Virginia (BB-48), where he became the ship’s heavyweight boxing champion. In July of that year he had temporary duty aboard USS Nevada (BB-36) at Secondary Battery Gunnery School. He returned to West Virginia on August 3 and was serving in that battleship when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Miller had arisen at 6 a.m. and was collecting laundry when the alarm for general quarters sounded.

He headed for his battle station, the antiaircraft battery magazine amid ship, only to discover that torpedo damage had wrecked it, so he went on deck. Because of his physical prowess, he was assigned to carry wounded fellow Sailors to places of greater safety. Then an officer ordered him to the bridge to aid the mortally wounded captain of the ship. He subsequently manned a 50-caliber Browning anti-aircraft machine gun until he ran out of ammunition and was ordered to abandon ship.

Miller described firing the machine gun during the battle, a weapon which he had not been trained to operate: hard. I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine. I had watched the others with these guns. I guess I fired her for about fifteen minutes. I think I got one of those Jap planes. They were diving pretty close to us.”

During the attack, Japanese aircraft dropped two armored piercing bombs through the deck of the battleship and launched five 18-inch aircraft torpedoes into her port side. Heavily damaged by the ensuing explosions, and suffering from severe flooding below decks, the crew abandoned ship while West Virginia slowly settled to the harbor bottom. Of the 1,541 men on West Virginia during the attack, 130 were killed and 52 wounded.

Subsequently refloated, repaired, and modernized, the battleship served in the Pacific theater through the end of the war in August 1945.

Miller was commended by the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, on April 1, 1942, and on May 27, 1942 he received the Navy Cross, which Fleet Admiral (then Admiral) Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet personally presented to Miller on board aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) for his extraordinary courage in battle.

Speaking of Miller, Nimitz remarked: “This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race and I’m sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts.”

On December 13, 1941, Miller reported to USS Indianapolis (CA-35), and subsequently returned to the west coast of the United States in November 1942. Assigned to the newly constructed USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56) in the spring of 1943, Miller was on board that escort carrier during Operation Galvanic, the seizure of Makin and Tarawa Atolls in the Gilbert Islands. Liscome Bay’s aircraft supported operations ashore November 20-23, 1943. At 5:10 a.m. on November 24, while cruising near Butaritari Island, a single torpedo from Japanese submarine I-175 struck the escort carrier near the stern. The aircraft bomb magazine detonated a few moments later, sinking the warship within minutes.

Listed as missing following the loss of that escort carrier, Miller was officially presumed dead on November 25, 1944, a year and a day after the loss of Liscome Bay. Only 272 Sailors survived the sinking of Liscome Bay, while 646 died.

In addition to the Navy Cross, Miller was entitled to the Purple Heart Medal; the American Defense Service Medal, Fleet Clasp; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal; and the World War II Victory Medal.

Commissioned on June 30, 1973, USS Miller (FF-1091), a Knox-class frigate, was named in honor of Doris Miller.

On October 11, 1991, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority dedicated a bronze commemorative plaque of Miller at the Miller Family Park located on the U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor.

Today there is an effort to upgrade Miller’s cross to a Medal of Honor. Texas Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson is instrumental in the push, but to date the effort has been unsuccessful. Some feel his race may have had something to do with not receiving the highest honor.

Miller’s 64-year-old niece is Henrietta Miller-Bledsoe. She told the New York Daily News she’s bothered by lingering skepticism over how many planes Miller had a hand in shooting down.

“It doesn’t matter if it was zero planes … At least he took the initiative to remove his captain and man the machine gun.

No Comment