By ZACH PLUHACEK

Lincoln Journal Star

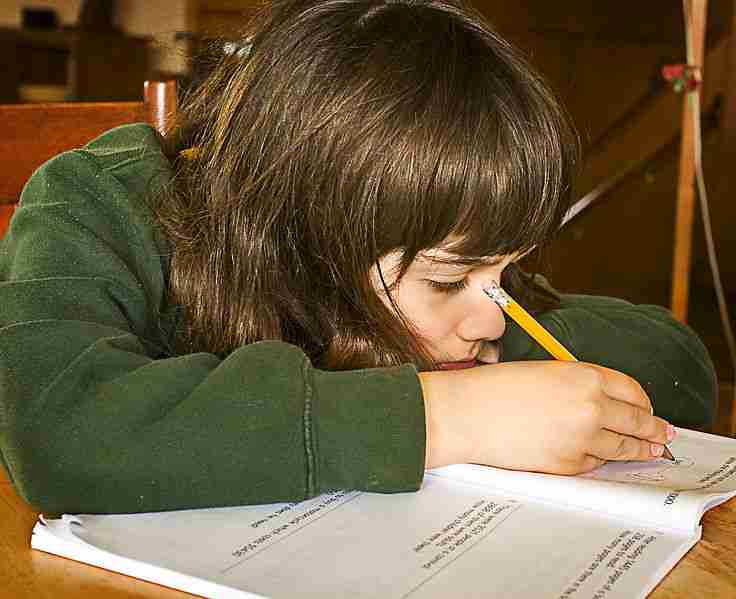

LINCOLN, Neb. (AP) – Reading made Alex Filing so physically exhausted that he would yawn mid-sentence – not out of boredom, but fatigue.

He’d toil away on homework with his parents, sometimes as late as 10 p.m., to no avail.

“We just knew we weren’t moving the needle very far, especially given the amount of work he was putting in,” said his mother, Shannon Filing.

But it wasn’t until Alex was in third grade – when he was still capitalizing his B’s and D’s to tell them apart – that his parents began to suspect dyslexia was the cause of their son’s struggles.

Shannon Filing became “a mother on a quest.”

She convinced his school to let Alex, now 13, use books on tape to achieve his assigned reading goals. Beginning in fifth grade, she and her husband started homeschooling Alex at their house in Panama, southeast of Lincoln. They also signed him up for reading intervention at Fix Lexia, a clinic in Omaha.

The Filings would like to see other children with dyslexia start invention earlier, but doing so requires more awareness by parents and thorough screening in schools, advocates say.

The Lincoln Journal Star (http://bit.ly/2iFNLLg ) reports dyslexia is believed to be the most common learning disability. It affects as many as 16 percent of children and adults and is inherited genetically, meaning babies born to a dyslexic parent have a 50 percent chance of being dyslexic themselves, said Dr. Eileen Vautravers, a retired Lincoln pediatrician and dyslexia advocate.

Yet the disorder is largely misunderstood. People with dyslexia don’t just read backward or flip letters; they struggle with phonemic awareness, or the ability to connect the sound of a spoken letter with text on a page.

Simply put, Vautravers said, “It’s difficulty with reading words.”

State Sen. Patty Pansing Brooks of Lincoln, whose family has a history of dyslexia and dyslexia advocacy, plans to sponsor a bill in the Legislature this year that would add a definition for dyslexia to Nebraska’s law books.

Her hope is to get the disorder “defined and on the map” statewide, then eventually add training for teachers to identify certain warning signs of dyslexia as early as kindergarten.

“I’m interested because of this historic family connection,” Pansing Brooks said.

When her brother Tom was in third grade, teachers said he’d never graduate high school. He now works at a partner at an Omaha law firm.

Prompted by Tom’s experience, their mother Lu Pansing became an advocate for a tutoring approach called Orton-Gillingham. She eventually secured a seat on the Lincoln Board of Education, in large part to promote dyslexia programming in public schools.

Dyslexia’s most visible indicators often don’t emerge until third or fourth grade, when students advance from reading words they know by sight memory and onto more complicated terms.

Yet if intervention – exercises to improve a child’s ability to read – doesn’t begin until third grade, studies show about 74 percent of students with dyslexia will continue to experience reading problems.

If intervention starts in first grade, fewer than 6 percent of those students will keep struggling.

“Early intervention is best because in those early years … our kids are learning how to read. But third grade or later, they are reading to learn,” said Rebecca Miller, managing director at Fix Lexia.

Most schools in Nebraska assess students’ reading ability early in their education, Miller said.

However, those screenings typically leave out known risk factors for dyslexia – such as the inability to rapidly name letters, numbers and colors, or difficulty discriminating individual letter sounds within words.

“By fourth grade, they’re so far behind their peers that it is difficult for them to catch up,” said Victoria Molfese, a professor in child, youth and family studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Education and Human Sciences.

Molfese and her husband Dennis research dyslexia and other learning disabilities at UNL’s Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior.

Brain imaging shows when people with dyslexia read, their neural activity lasts longer and is distributed across larger parts of the brain than in other people, Victoria Molfese said.

That means dyslexic readers literally take longer and use more brain capacity to process individual words, which impacts their comprehension of larger texts.

It’s like hearing someone read a single word at a time in 10-second intervals, then trying to string those words together into a normal sentence – which could cause a headache for anyone.

Dennis Molfese recalled doing a study of 8- to 12-year-olds at a school district near Louisville, Kentucky.

“When we gave the report at a teachers meeting weeks later, one of the children spoke up and said, `See Mom? I really am using my whole brain. I really am trying,”’ he said.

Virginia Johnson, Sen. Pansing Brooks’ cousin, never had to convince her own mother.

When she was in seventh grade in the 1950s, a counselor at Irving Junior High suggested Johnson switch to special education courses because she was struggling to read.

Johnson’s mother said no.

Instead, mother and daughter read Johnson’s homework out loud to each other almost every school night for three years.

“I compensated for my dyslexia by working my tail off,” Johnson said. “Many dyslexic students do that. They just compensate.”

Despite struggling with the alphabet into high school, Johnson made the honor roll as a junior and senior, became a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society at UNL, earned a degree from the University of Nebraska College of Law and spent 20 years as a practicing attorney.

She wasn’t formally diagnosed dyslexic as a child, and didn’t have much awareness of the disorder until her oldest son was born with dyslexia. Lu Pansing, Johnson’s aunt, trained her to tutor him using the Orton-Gillingham Approach.

Parents know when their children are intelligent, Johnson said.

“You see in their play, in their imagination, you overhear conversation with their friends. These are young children that just excel in so many different ways,” she said. “This is not a parent making an excuse for a child not succeeding. This is a scientifically based disability, and it should be treated that way.”

___

Information from: Lincoln Journal Star, http://www.journalstar.com

No Comment