By Juliana Acciola

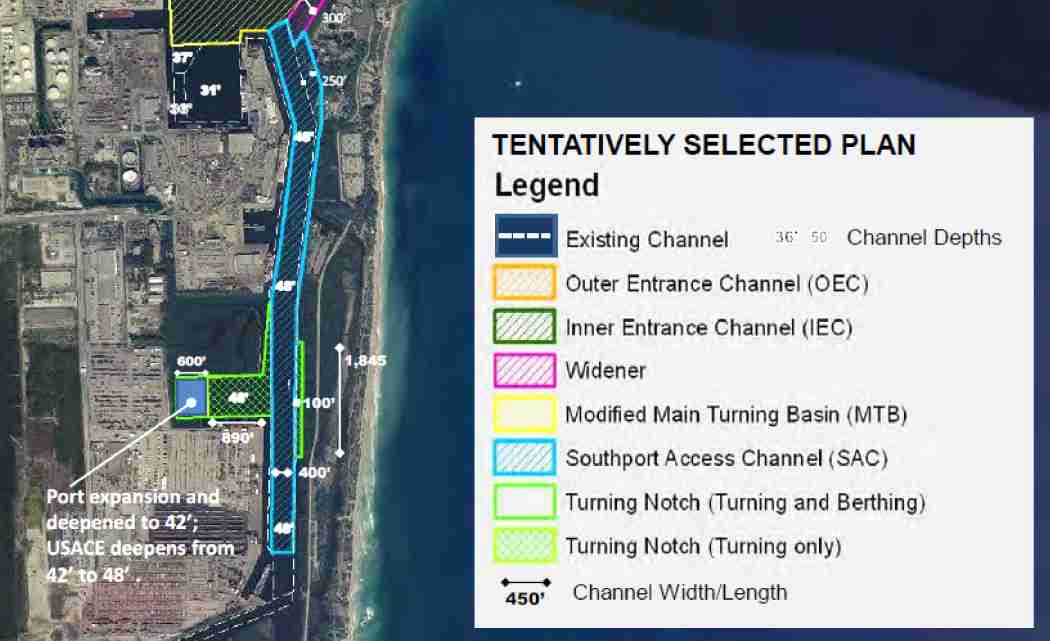

The controversial dredging in the PortMiami is approaching to completion in July 20.

The $180m project that is deepening the port’s channel to 50 feet will clear the way for Post-Panamax megaships, making the port a major logistics hub connecting Asia and Latin America. The second producing agent of revenue in the county, the port now contributes nearly $27 million annually to the local and state economies and supports 207,000 jobs in the State of Florida.

PortMiami’s expansion is expected to boost local economy by doubling the cargo traffic and generating more than 20,000 new jobs.

But industrial projects involving natural resources come at a price. In early June scientists from the University of Miami and Coral Morphologic reported excessive sediment damage to corals in the area of the deep dredge. An inspection by the Miami-Dade County’s Division of Environmental Resource Management followed, finding a blanket of silt and clay over the bay bottom.

“I have never seen reefs like the ones near the dredging,” says Rachel Silverstein, Biscayne Bay Waterkeeper Watchdog executive director. “It is covered in sediment that is smothering the reef; it is all fine dust.”

In September the group filed a suit with the Tropical Audubon Society, Captain Dan Kipnis, and Miami –Dade Reef, claiming that the project violated the Endangered Species Act, in addition to several permit conditions by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. The complaint alleged that the Army Corps of Engineers shifted away from being environmentally sensitive by failing to monitor the turbidity in the water and moving its dredge ships away from reef areas, causing irreparable damage of staghorn coral colonies.

Prompted by the suit, on Oct. 23 the Army Corps acceded to pay $400,000 to rescue hundreds of threatened corals from near the dredging and reinforce best practices. The project now includes the restoration of more than 16 acres of sea grass and the creation of over nine acres of artificial reef.

Laura Reynolds, executive director for the Tropical Audubon Society says the mitigation efforts are a work in progress. Hundreds of coral fragments were moved to University of Miami nurseries for restoration, but “the port was supposed to shut down operations until turbidity is down and that has not happened.”

Coral reefs and the marine life they support are critical to the survival of Miami’s tourism, diving, fishing and seafood industries, all engines for the local economy. “We have a whole economy based on reef resources, a real unique thing,” says Silverstein. “Nobody is talking about how this is going to affect small business owners and the community at a large.”

Another factor in the equation is that some coral reefs buffer adjacent shorelines from wave action and prevent erosion – without reefs the coast could become more vulnerable and potentially increase Miami’s flooding problem. The Union of Concerned Scientists’ studies have shown that tidal flooding in the city will keep increasing as sea levels along the northeastern United States’ Atlantic coast have risen a rate three to four times faster than the global average. Ankle-deep water on Washington Street and Alton Road in Miami Beach could become a more frequent occurrence.

The question of just how much hurting the environment is outweighed by economic development is a delicate one. In this case, ports must expand to stay within the global commerce route and mitigation has to be carefully planned. Silvertein says she is curious about how the past will inform the decisions made by other ports, such as Port Everglades, which has even greater and more sensitive coral and seagrass resources.

Still pending approval, the port’s expansion is estimated to cost about $370,000, an investment to be offset by revenue increase and about 480,000 temporary jobs, including the designing, engineering and the actual dredging. Ellen Kennedy, spokesperson for Port Everglades, says the project has been in the making for 17 years due to reasons that include seeking clarity on how to best safeguard against damage.

David Bernhart, Fishery Management Officer at National Marine Fisheries Services, says that NOOA has already provided a consultation to the Army Corps as to the potential sedimentation next to the channel to help ensure a more stringent environmental review.

“If we ended up with some major lessons learned from Miami, we must implement them.”

No Comment