PORT-AU-PRINCE — Back from exile, former strongman Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier lives in a villa in the hills above Haiti’s capital. His son serves as a consultant to the country’s new president, Michel Martelly, while others with links to Duvalier’s hated and feared regime work for the administration.

Duvalier himself is rumored to be ill and appears too frail to return to power. But, for many Haitians who remember the ex-dictator’s brutal rule, the rise of his loyalists to the new president’s inner circle triggers suspicions about where Martelly’s loyalties lie.

Such developments might be shrugged off in many countries but not in Haiti, where much of the political establishment for the past 15 years has consisted of people associated with the mass uprising that forced “Baby Doc” to flee to France in 1986.

Now, a former minister and ambassador under the regime has been a close adviser to Martelly and was recently nominated to the Cabinet. At least five high-ranking members of the administration, including the new prime minister, are the children of senior dictatorship officials.

Sen. Moise Jean-Charles said he and others who lived through those years are uneasy that Duvalierists are aligned with a president with no previous political experience and a history of supporting right-wing causes.

“They’ve been nostalgic for 25 years,” Jean-Charles said of Duvalier’s supporters. “And now, they’re back in the country and back in power.”

Martelly’s powers will be at least partly held in check because his opponents control both houses of parliament. Nonetheless, Jean-Charles, an ex-mayor under former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, has taken his concerns to radio stations and the senate floor. Human rights advocates have echoed similar warnings, especially after a raucous protest staged by Duvalier supporters last month disrupted a news conference calling for the ex-dictator’s prosecution.

“There’s a lot of worry,” said Haitian economist and sociologist Camille Chalmers. “The political circle is made up of Duvalierists.”

Martelly spokesman Lucien Jura told The Associated Press that the appointments were based on individual qualifications, rather than political affiliation.

“As President Martelly said before, he’s not excluding (anyone),” Jura said. “ If the citizen is competent, honest and has good will … regardless of the political sector he’s in, he’s welcome.”

The new government includes a few veterans from Aristide’s government, including Mario Dupuy, a communications adviser who was chief spokesman during Aristide’s second term.

Martelly met with Aristide and Duvalier on Oct. 12 in an effort to reconcile differences between the former leaders and their followers. The day before, he met with Prosper Avril, an army colonel who overthrew a transitional government in 1988 and resigned two years later amid protests.

“It’s time for us again to be one nation, stand behind one project,” Martelly told the AP outside the plush home where Duvalier is staying.

While running for office, Martelly pitched himself as a populist even if he later imposed taxes on remittances and phone calls from abroad to help pay for the free schooling of 772,000 children. He’s also pledged to build housing and create jobs for some of the half million people still homeless nearly two years after an earthquake devastated the country.

While Martelly hasn’t publicly voiced any support for Duvalier, he’s addressed some of the top priorities of Duvalier’s relatively small political base since taking office in May.

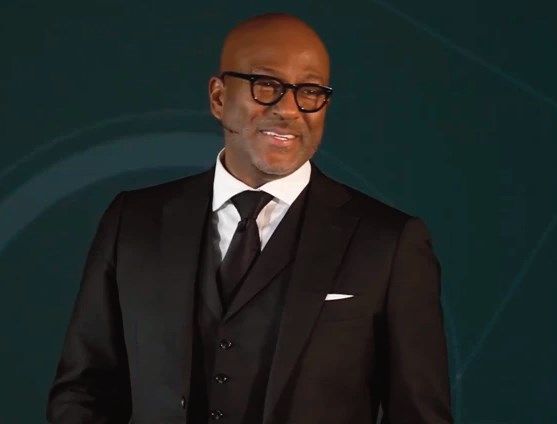

Photo: Michel Martelly

No Comment