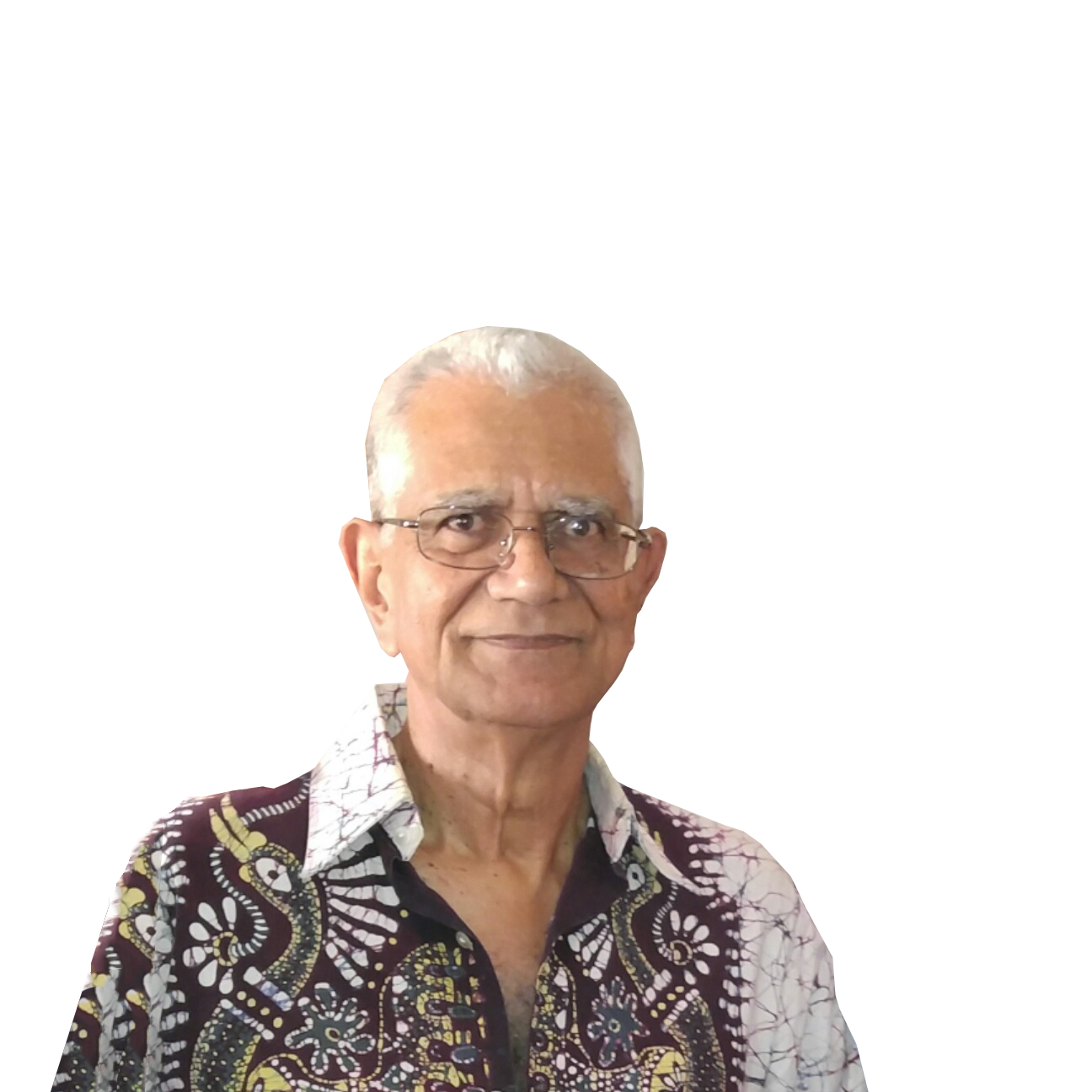

By MOHAMED HAMALUDIN

American foreign policy has been woefully inadequate towards the Anglophone or English-speaking Caribbean, an area characterized by more than half a century of political stability, except for a couple of blips in Trinidad and Tobago and Grenada.

Washington has traditionally pursued a relatively hands-off policy towards the region, in deference to the British, the former colonial overlords, pointing up a contradiction in U.S. international relations in which the United States has been pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into hot spots elsewhere but sending relatively little aid to stable nations. Some wags in the Caribbean have been known to say that it would be better to stage a few coups just to get similar attention.

One initiative, , the Caribbean and Central American Action (CCAA), started in 1976, held its 40th anniversary conference in Coral Gables last November. Another effort, the Caribbean Basin Initiative of 1983, offered tariff and trade preferences. Both sparked high hopes in the English-speaking Caribbean for better economic relations with the United States but they did little to advance the development of this part of the world where the American profile surpassed that of Britain long ago.

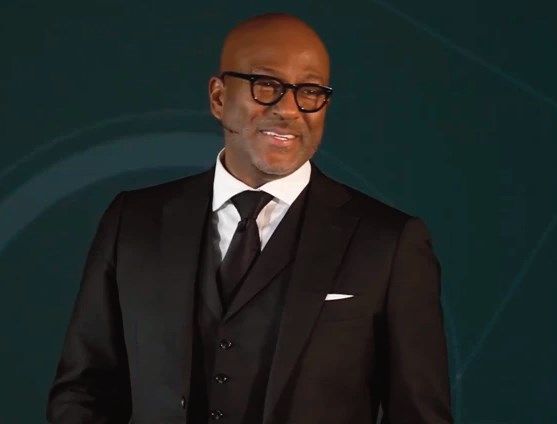

The late California Congressman Mervyn M. Dymally, a native of Trinidad and Tobago, pushed in the 1980s for just such greater involvement. His efforts brought him at least once to the Miami area to meet with members of the Caribbean diaspora. But, again, not much came from his efforts.

The region has not been standing still waiting for help. The West Indies Federation was created in 1958 to forge political unity but the experiment collapsed four years later through internal bickering. A less ambitious Caribbean Free Trade Area

(CARIFTA) was formed in 1965 and, in 1975, a major breakthrough came with the establishment of the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM), initially by Barbados, Jamaica, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.

This latest grouping seeks ways to marry political unity and trade and economic linkages. But it, too, has not garnered much attention from Washington, except as pawns in the “cold War” confrontation between the then Soviet Union and former European colonial powers and the U.S. More recently, Europe and the U.S. have embarked on a never-ending “war against terror” that similarly leaves little space for Caribbean concerns.

This neglect has left a vacuum of sorts in the region and China has been eager to offer itself as an international partner, especially in Guyana, capitalizing on a leadership rift that saw Guyanese leader Cheddi Jagan ally himself with the Soviet Union and, later, Cuba, and his political rival Forbes Burnham adopting a “nonaligned” philosophy that the Chinese found attractive.

China built a textile mill in Guyana in the 1970s — even though the country never had a cotton industry. The Asian economic powerhouse is now likely to build a bridge across the Corentyne River to link Guyana and Surinam to the east.

So it was intriguing to read a mid-December report in The Miami Herald by Jacqueline Charles that President Barack Obama, among his final acts in office, signed the United States-Caribbean Strategic Engagement Act. The story described the legislation as “a multi-year strategy on issues of concern to the region such as security, energy, diplomacy and increased access to educational opportunities.”

Obama missed a great opportunity to showcase this part of the world as an example of what stability means. He visited the region at least twice, so he did not totally ignore it but with the end of his presidency the fate of the new legislation is unknown. There is no reason to believe that U.S.-Anglophone Caribbean relations will shift into high gear under the new administration. There is no indication that either President

Donald Trump or his proposed federal appointees have any strong affinity towards the region.

Whether or not anything happens could depend on the reaction of African Americans and the nearly two million members of the English-speaking Caribbean diaspora. They can still become the vanguard in the awakening towards the benefits of much more robust relations.

While a small handful of activist Cuban Americans in Congress, playing on anti- Castro sentiments, succeeded in making Cuba central to the policy towards the region, African Americans and Caribbean Americans have so far been less than enthusiastic in trying to broaden the focus to the English-speaking nations. The legislation which Obama signed offers an opportunity to change that dynamic.

No Comment