PHOTO COURTESY OF TAIPHILA.ORG

Darby, Pa, (AP) – Alma Bailey wanted to be an opera singer.

Instead, she served her country in a time of war, segregation and racism. At 95, the native Kentuckian uses her voice – but not for music.

She mentors young people in her home of Philadelphia and uses her experience during World War II as a Tuskegee nurse to educated young people about the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, a group whose claim to fame includes flying more than 15,000 combat missions and earning 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses.

“Most of all the Tuskegee Airmen and Tuskegee women are in our 90s and 100s and we don’t want to lose … the fact that Tuskegee Airmen did exist, Tuskegee women did exist,” Bailey said in a voice that smiled all on its own.

Her nephew, Howard Bailey, a retired vice president of student affairs at Western Kentucky University, said her story is important because she was a pioneer not only for her family but for the nation. His special connection to his aunt started when she delivered him at an Eastern Kentucky hospital. He first pitched her life as a perfect tale for Black History Month, which is every February.

Members of the Bailey family were miners in Middlesboro at the turn of the 20th century, but Howard said the push for education started with his grandparents.

“Alma was one of those that got out of Appalachia at a time when that was next to impossible and had an outstanding career,” said Howard, who lives in Bowling Green. “She was able to contribute to the United States through her nursing career at a time when the Red Tails were already making history.”

STEPPED UP, DID SOMETHING

When wounded men were coming home, they needed people to care for them.

“She’s one of the women that stepped up and did something,” Howard said.

Before the Tuskegee Airmen – the first black flyers for the U.S. Army Air Corps – nudged the military toward racial integration, Bailey worked in the segregated worlds of nursing and the military.

Tuskegee Airmen PHOTO COURTESY OF HISTORY.COM

The nurses like Bailey who were part of the “Tuskegee Experience” often dealt with compounded discrimination – they were black and female. In World War II, out of an estimated 50,000 Army Nurse Corps nurses, only 500 were black.

Because “Uncle Sam needed nurses” and because her mother told her she had to, the Middlesboro native went to Tuskegee, Ala., for training in 1943.

“Uncle Sam don’t need no music, no operas with this war going on,” her mother told her.

And young Alma Bailey had to listen. Not only because “back in those days, children minded their parents,” she said, but because her mama had stuck her neck out so she’d have the opportunity.

In the height of the war, the call had gone out in rural Kentucky that wounded soldiers were coming home, and there was a shortage of nurses. But only the white high school girls were recruited.

CHOSE TUSKEGEE

“My mother and the gang of black women got together and confronted this superintendent,” Bailey said. “They confronted him, and he stuttered but he said he would check and see why he wasn’t notified to tell the black schools.” Two weeks later, the white superintendent got permission to send black girls off for training. But the girls had only 14 days to make a decision on where they wanted to go.

Bailey had heard Alabama was teeming with Ku Klux Klan members. She chose Tuskegee anyway. It was either go to Tuskegee, the institution from which her father graduated in 1914, or her mother’s alma mater, Knoxville College.

The experience, from 1943 to ’45, was “terrifying,” she said.

She took a train and breathed in its smoke until she arrived at a little platform station 5 miles from campus. It was 2 a.m., and she was 17 years old.

Bailey remembers the white man who asked her where she was going. She was scared for her life.

She got into the car of a stranger who said he was there to pick up the new nursing students.

And she remembers a big man with a gun guarding the gated campus that would be her home for the next 2 1/2 years.

During the 30 months she learned how to care for the injured men returning stateside, Bailey suffered racism that still haunts her.

Men who were emotionally damaged and physically injured flooded the hospital she was assigned to in Alabama. She remembers treating their wounds while navigating a hazardous environment for women.

RAPE, ROUTINE

The young U.S. cadet nurse was once thrown onto a bed in the segregated ward she was working. A patient tried to rape her.

It was common business, she said, nurses getting raped.

“You would either get raped by the patients or you would have to date the attendants to protect you,” she said. Since she chose not to date for protection, “that’s how the guy got close to me.”

She kept a ruler in her bib and when she was attacked, she said, she pulled it out and beat her attacker on top of his head. “I had to defend myself,” she recalled. She was able to escape.

She giggled as she remembered that the captain transferred her attacker, who’d been suffering from memory loss, to a different ward after that incident because her strike on his head helped his memory return.

School officials always warned the young women not to leave campus. But once, news of a $1 shoe sale in town was too good to turn up. It was perfect timing for the dance Bailey and nine of her friends wanted to attend with some airmen.

DON’T TOUCH THE CLOTHES

While they were looking at shoes with the help of three white clerks, a black woman walked in and pulled a dress from the rack to examine it. That’s when the white clerks rushed over to her.

“They went over and hit the lady,” Bailey remembered. They screamed at her.

“Oh no, you know not to come in here and touch any clothes. You know better,” she remembers them screaming at her. The racism scared the young nurses, “so we dropped our shoes and left. We went flying back to campus.” When they got back, they burst into tears.

“We thought maybe we should have stayed there and defended her,” Bailey said. But they worried about being caught in the middle of a fight with the KKK, possibly nearby.

“That is still on my memory today,” she said. “Should we have stayed and helped the lady? They were yelling and screaming at her and she was crying.”

Bailey never became an opera singer and she never married. Any husband she’d have picked “would have needed wings,” her nephew said, just to keep up with her career, which took her all around the country.

Before she “fell in love” with the Catholic Church and converted to Catholicism, she wet her whistle singing in a Baptist Church choir. She retired from nursing in 1987.

In more recent years, she’s been an active member of her Philadelphia Tuskegee Airmen chapter as well as her church, the Blessed Virgin Mary Parish in Darby, Pennsylvania.

And a source of pride for her, she said, is that her family worked to get the Martin Luther King Jr. monument in the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

NO “MISS BAILEY”

Alma Bailey has seen a lot of changes in her 95 years, but she said racism hasn’t died.

“You never actually feel free, being black” she said.

Racism “isn’t gone,” in her experience. Though she has many white friends, she said some white people she meets still can’t accept a person of a different skin tone. “The times change but we see it developing again. It’s not gone. There’s no total freedom.”

An example she often comes back to is her move to Philadelphia in 1955. She moved to continue her nursing work and she thought that people in the north would be more open-minded.

It wasn’t the case. Her colleagues there refused to give her the courtesy afforded white nurses: She wasn’t called “Miss Bailey.”

They would only call her “Alma.”

ACTIVE MEMBER

Bailey is an active member of the Greater Philadelphia Chapter of Tuskegee Airmen Inc.

The chapter works to raise funds to send as many young people as possible off to college with scholarships.

Part of the chapter’s work involves taking little children to airports and teaching them the beauty of flying.

“We campaign and we raise money so we can send any child, no matter what race, to college. That’s our purpose,” she said. “We work hard to give scholarships.”

A little black girl told Bailey recently that she wanted to be an astronaut. It’s moments like those that make her work worth it, she said while squealing with delight.

“That makes me so happy.”

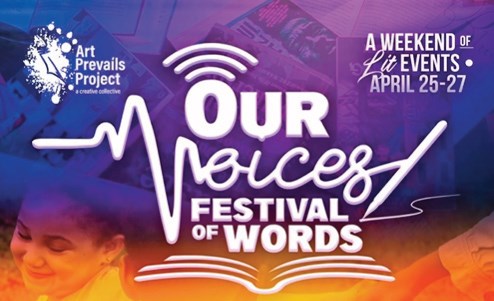

No Comment