NEW YORK (AP) — Imagine making the move of your young life twice. That's what several young men from Senegal have done.

First, they left home just as they became teenagers for Dakar, the nation's capital, to attend an academy that would prepare them for the next step —the chance to go to the United States and, through basketball, have a chance at a quality education.

While young men from Africa have been coming to the United States in growing numbers, the idea that reaching the NBA is their only goal is off, way off.

Through a program called SEEDS — Sports for Education and Economic Development in Senegal — education comes before basketball.

“It was a tough decision to leave home but as I was leaving my dad said he didn't care about basketball. He wanted me to study,” said Louisville center Gorgui Dieng, a preseason All-Big East selection.

“SEEDS is a great program, a chance to go to school and maybe play college basketball. If four or five of us do well then that will let others know what we have done. … We want to go home with the education we earned here and make sure others have the same chance. Maybe one day I will work for our government.''

SEEDS is not affiliated with the Senegalese government. It is a nonprofit foundation started in 2002 by Amadou Gallo Fall, a native of Senegal who came to the United States and was able to work in basketball, eventually landing a position with the Dallas Mavericks.

He was able to form the strategic plan for SEEDS, one that for the first decade has worked well while leaving plenty of opportunity for growth as the NBA continues to expand internationally.

Since Aziz N'Diaye became the first SEEDS graduate to play at an American college — the University of Washington — the Senegalese students have kept coming.

Baye Moussa Keita was a 6-foot-6, 14-year-old soccer player growing up in Senegal. The coach of his youth team encouraged him to attend a small clinic so officials from the organization could see him.

A year later Keita left his parents and six siblings to attend the SEEDS Academy. It turned out to be a great move. After graduating from the academy, Keita headed for the United States and eventually a basketball scholarship at Syracuse.

Keita, who grew up speaking French and Wolof, the native language of Senegal, said it took a few months at Oak Hill Academy in Mouth of Wilson, Va., to feel comfortable with English.

“Everything was just different but that really helped me,” he said. “I feel like I've assimilated well.”

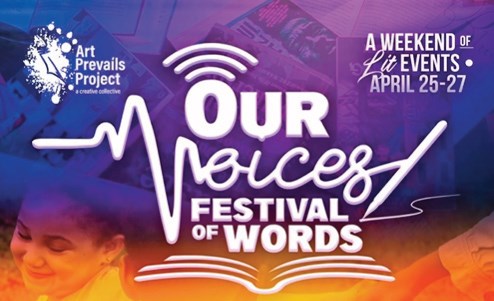

That is all part of what SEEDS does. Anne Buford directed a documentary about SEEDS called Elevate. The film stays with four young men as they go through the SEEDS program at home and then their arrival at different schools in the United States. It's powerful as the film shows how much this chance means to those chosen. It is about an opportunity of a lifetime.

“Americans tend to view Africa through a distorted lens,” Buford said. “When we think of Africa we think jungle, poverty, guns — a floundering continent.

But I had on my hands a real story about men helping other men, about hope and opportunity, not pity. Through basketball, these kids were learning life skills and earning their ticket to an education.”

Youssoupha Ndoye is a sophomore at Saint Bona- venture. “SEEDS was a learning experience. I can say everything I've learned basketball-wise and social-wise was because of SEEDS,” he said.

“There was probably like 22 people in the dorms, all males, and we all played basketball. We'd go to the same school together, we'd have the bus come pick us up, go to school, come back and practice. It was so serious. They take basketball serious but education first, then basketball.

“Their goal was for us, once we come here, to not be surprised. To not have culture shock as bad as if you didn't learn anything there, basically to follow the rules like you'd have here. We was all like a family, the people that went there. I found my best friend there — we still talk every day — so it was really a good experience.”

No Comment