MANNING, S.C. – A hearing that supporters say could exonerate a 14-year-old boy executed in 1944 in the killing of two girls will likely take place in the next month, a prosecutor said.

MANNING, S.C. – A hearing that supporters say could exonerate a 14-year-old boy executed in 1944 in the killing of two girls will likely take place in the next month, a prosecutor said.

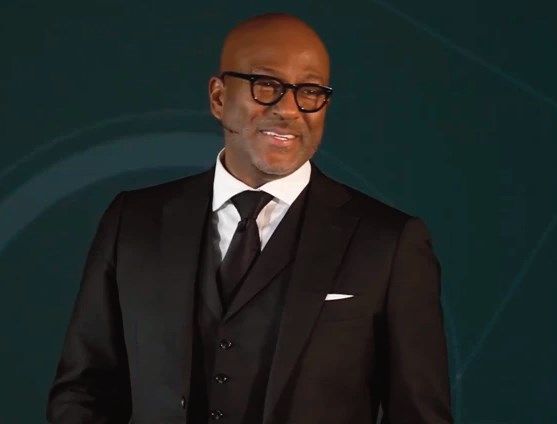

Solicitor Ernest A. “Chip” Finney III came to a rally by civil rights groups who want to keep pressure on officials to clear George Stinney of all charges in the death of two girls in Clarendon County.

Finney told the crowd he has no evidence to argue against a new trial for Stinney. The trial has been requested by a law firm working on behalf of Stinney’s supporters. If a judge agrees, Finney said his office will have to review whatever evidence they can find in the 69-year-old case.

It may not be much. The confession authorities used at the time has disappeared. Supporters have suggested it was coerced through threats or an offer of ice cream.

Any transcript or other information from the trial is gone. All that is left at the Clarendon County courthouse are a few pages of cryptic, hand-written notes, according to the motion seeking a new trial. Finney said South Carolina has never seen a case like this.

“I have to operate my office by the rules and regulations of the court system, even though I might have a heart that says this young man was not treated fairly and I want to give him a second chance,” Finney said.

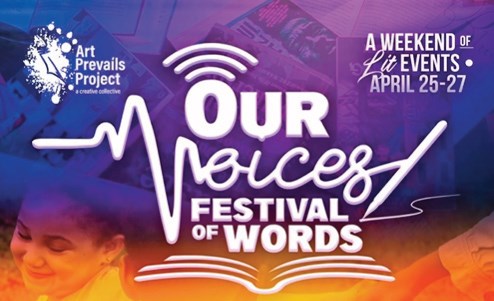

The rally was organized by George Frierson, a local school board member who grew up in Stinney’s hometown hearing stories about the case. He decided six years ago to start studying it and pushing for exoneration.

He carried with him a two-inch thick binder full of stories, autopsy results, pictures and other evidence. “I don’t see anything that is right. That’s why we are demanding justice,” Frierson said from the front of the sanctuary at Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church in Manning, where, 60 years ago, groups gathered to discuss their plans for the case that would eventually become Brown v. Board of Education.

Frierson said he isn’t happy that Stinney’s exoneration may come down to a single judge elected by the state Legislature. He will reluctantly seek a pardon if the judge rules against a new trial.

“The word ‘pardon’ [means] to be forgiven for what you have done. He didn’t do anything,” Frierson said. At 14, Stinney was the youngest person executed in this country in the past 100 years, according to statistics gathered by the Death Penalty Information Center. The black teenager was executed just 84 days after the two white girls were killed in the tiny mill town of Alcolu, according to newspaper accounts. The electrodes from the electric chair were too small to fit on his leg, according to the articles.

The request for a new trial points out that, at 95 pounds, Stinney likely couldn’t have killed the girls, ages 11 and 7, and drag them to a ditch where they were found dead from being beaten in the head, likely with a railroad spike.

The girls were headed to the poor side of Alcolu to pick flowers that day and deputies received a tip Stinney had been seen talking to them.

Authorities never spoke to Stinney’s family. His sister would say later that she was with them the girls and her brother the time. She said the girls asked her brother where to find flowers and he told them he didn’t know and walked away.

The rally started on the steps of the Clarendon County Courthouse, where Stinney was the only black face among the hundreds of people in the courtroom when he was tried in 1944. His family never saw him after his arrest.

Members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People were there, along with about a dozen relatives of Stinney and a ninth-grade class from Kingstree High School.

Graduation Coordinator Towanda Tisdale said she picked those students because they are of Stinney’s age. The U.S. has since outlawed executing anyone under 18.

No Comment