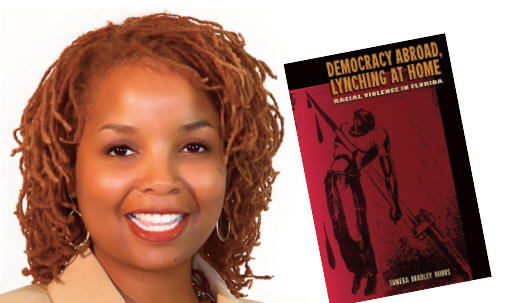

MIAMI GARDENS, Fla. – Seventy two years have passed since Willie James Howard was lynched in Live Oak, Florida, decades before her birth; but the sadness of that tragic murder still cloaks Tameka Bradley Hobbs’ words as she describes what happened to the young man in the county seat of Suwannee County, located east of Tallahassee.

The Florida Memorial University history professor said she learned of Howard’s lynching from a professor while she was an undergraduate student at Florida A & M University. After a painful discussion with her grandfather, who was a young man in Live Oak when Howard was killed, Hobbs decided that her graduate research at Florida State University would be devoted to unearthing Florida’s racial violence during the 1940s.

She eventually wrote a book about the lynchings of Howard and three other black male Floridians in her book, Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home: Racial Violence in Florida, for which she was recently awarded the Bronze Medal in the Florida Book Awards.

Published in 2015, the book’s origins go back to Hobbs’ time at FAMU when, “in class with Dr. Ted Hemingway he started talking about lynching and he turned to me and said, ‘I bet you don’t know that they lynched a boy in Live Oak,’ which is where I’m from,” she shared.

“I was confused…how could something so terrible happen in my hometown and I never hear about it? And sure enough, the next time that I went home, I talked to my grandfather and we had a very difficult conversation around what he remembered about the lynching of Willie James Howard, who was killed Jan. 2, 1944.”

Hobbs said during their talk, she saw a side of her grandfather that she’d never seen before.

“I saw in him that day in just him remembering those times in his life a fear. In the book I call it a ‘shrinking.’ He was larger than life; he ran his house, our family with a very firm manner. This is a man who was always in control,” she shared, “but what I saw in his face that day was fear and terror still.”

Her grandfather also recalled choices he was required to make in order to survive. “He went on to tell me that as a young man if he would be walking to town and he saw a white woman approaching him on the way, he would turn around and go home because anything could happen. Any accusation could cost him his life.”

Hobbs’ delving into Florida’s dark history continued at the request of Professor Hemingway for a project that he was working on that never materialized and ultimately became the focus of her graduate studies.

In addition to Howard, she also researched the lynchings of Cellos Harrison, who was murdered in Mariana in 1943; Jesse James Payne, who was lynched in Madison in 1945 and Arthur Williams, whose sister Hobbs interviewed about his 1941 lynching in Quincy, Florida

“She was nine-years old when her brother was killed. It was her favorite brother she said. And she told me this horrific story,” Hobbs shared. “He had been accused of robbery and attempted rape and he was held in jail.”

A vicious white mob broke into the jail, took Howard out and strung him up. As they drove away, someone fired a shot that Hobbs said, “must have grazed the rope, he fell to the ground and he was able to survive that attack.”

Bleeding and in need of medical care, Howard returned to his family, who initially hid him because he informed them that the sheriff had been involved in his kidnapping. Hobbs said the family even joined the search party and pretended to look for him, but eventually had to alert the authorities because his medical condition had severely declined.

Because there were no hospitals in Quincy that would treat a black person, Hobbs said arrangements were made to transport him to Tallahassee, where he could be seen at Florida A & M College’s hospital.

On the way to Tallahassee, however, the vehicle was stopped by masked men and Howard was taken out and killed.

Hobbs said his sister (for whom she used the pseudonym, Ann Flipper, in her book) recalled that a white man brought her brother’s body from the back of a truck and put it on her mother’s porch and said “Here, Hattie, here’s your son.”

Irvin D.S. Winsboro, editor of Old South, New South, or Down South?, said of Hobbs’ book, “A compelling reminder of just how troubling and violent the Sunshine State’s racial past has been. A must read.”

Coordinated by the Florida State University Libraries, the Florida Book Awards is the nation’s most comprehensive state book awards program. It was established in 2006 to celebrate the best Florida literature. Hobbs and the other winners will be honored at the Abitz Family Dinner, the annual awards banquet, which will take place in Tallahassee on April 7 at the Mission San Luis.

Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home (University of Florida Press) is available at tamekabradleyhobbs.com

No Comment