By BRETT ZONGKER

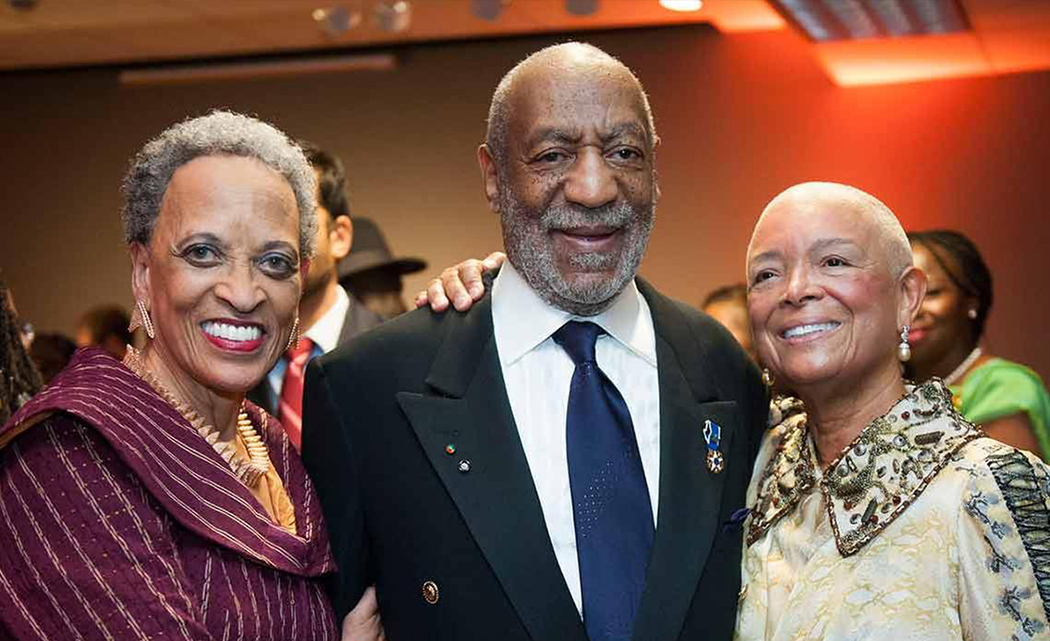

WASHINGTON (AP) — Everybody knows Bill Cosby’s humor, but the comedian has kept his artistic tastes close at home. Now the extensive art collection of Bill and Camille Cosby is opening to the public for the first time Sunday at the Smithsonian Institution, revealing some works by African-American artists that until now have been seen only by family and friends.

The exhibition not only celebrates African-American heritage, it also provides a glimpse at works the Cosbys have enjoyed intimately, with pieces ranging from a masterwork that had remained hidden for a half-century before Camille Cosby recognized its value, to a quilt made from their slain son’s clothes. More than 60 artworks from the Cosby collection are being displayed through early 2016 alongside 100 pieces of African works at the National Museum of African Art in Washington.

Surrounded by these artworks in a Smithsonian gallery, the Cosbys sat down to discuss their passion for collecting, and Bill Cosby let his wife take the floor, describing how they came to love art together and their hopes that the exhibit will foster a new appreciation for works by black artists long silenced or ignored.

“I hope that people will become emotionally attached to these paintings,” she told The Associated Press. “I really want people to feel something.”

A centerpiece is “The Thankful Poor,” painted in 1894 by Henry Ossawa Tanner, a son of slaves who went to Paris and painted scenes that dignified black people at a time when they mostly suffered degrading images in popular culture.

The work depicts an elderly man and young boy in prayer at a humble dinner table. It had been left in basement storage at the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf for 50 years. Camille Cosby found the painting up for auction in 1981, and bought it for $250,000 as a Christmas gift for her husband. The bidding had started at $50,000.

“We didn’t collect to increase our assets because there weren’t any real values placed on art by African-Americans, no monetary value nor artistic value,” Camille Cosby said. “We collected because we really loved the pieces. We wanted to live with them.”

The greatest gift from amassing some 300 pieces of African-American art kept in their homes was that their children and grandchildren’s self-perceptions have been reinforced by positive images of black people, she said.

The Cosbys began collecting art in 1967, three years after they were married. Bill Cosby said he grew up in a housing project where a clock, a picture of Jesus, and cutouts from Ebony magazine passed as art.

When he had a house of his own, a taste of success in entertainment and rich friends, he noticed “these people have art, and it’s all white people.” The Cosbys started purchasing works by artist Charles White and almost immediately got hooked on collecting.

Bill Cosby featured paintings by black artists on the set of his early TV sitcom “The Bill Cosby Show” where he played Chet Kincaid. Later, he included African-American art on the walls of the Huxtables’ living room in “The Cosby Show” series.

“It pulls in the humanitarianism of this African-American family,” he said.

Some of the oldest works in the Cosby collection include rare portraits from the late 1700s and early 1800s by Joshua Johnston, a Baltimore-based African-American artist who was at one time a slave. The family also collected works by emerging artists and noted artists, including works by Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence and Faith Ringgold.

“These artists, it’s amazing to me that they did this work despite everything else that was around them politically, sociologically. It was difficult,” she said.

Now they’re getting their due in “Conversations: African and African American Artworks in Dialogue.”

But Bill Cosby joked that he had no idea his wife agreed to lend the works for an exhibit until curators began taking paintings off the walls.

“My paintings, these things happen to be my life,” he said. “When I come home, I talk to them.”

The Cosbys also collected and commissioned family quilts as a way to tell stories. Two of them on display include a creation by Ringgold as a tribute to Bill Cosby and a large quilt by the Mississippi Crossroads Quilters entitled “The Ennis Quilt,” made of scraps of son Ennis Cosby’s clothing after he was killed in 1997.

Many times, that quilt still covers their bed at home, Bill Cosby said.

Curators said they looked for the best works from the Cosbys and powerful pieces from the Smithsonian’s African art collection to pair works by black artists from two continents. Themes range from spirituality and humanity to political power, family life and music to drive the exhibition.

Some works are infused with a comedic touch, as well. Margo Humphrey’s lithograph “The Last Bar-B-Que” is a play on Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” where instead all types and colors of people, men and women, are at the table with Jesus, ready to eat watermelon and fried chicken wings.

“What you are going to see here is art by the descendants of people from various parts of that vast continent who even under tyranny in this nation were able to create beautiful works of art beyond the status of where they were in life, beyond slavery, beyond segregation, beyond Jim Crow, beyond racism,” said art historian David Driskell, who helped curate the show.

Cosby has been in the news lately as he prepares for a new sitcom on network television 30 years after his groundbreaking role as Cliff Huxtable on “The Cosby Show,” and because reviewers have criticized his otherwise comprehensive authorized biography published last month for making no mention of past accusations of sexual assault. Cosby declined to comment when asked for his response during the interview. The allegation stems from an investigation and lawsuit settled in 2006. Cosby has never been charged with sexual assault.

No Comment