After writing three works of fiction, anchored in contemporary themes, it was time to for me to write a novel that placed great emphasis on the many African-American accomplishments that occurred early in our history.

[optinlocker]

The Ideologies of African-American Literature, written by Washington, carefully outlines the dearth of historical fact from the pens of African-American writers.

Washington noted and I quote, “In the preindustrial structures of domination, the ruling group typically controls not only the subordinate group’s economic and political life, but also its cultural representations — namely the ideas and images inscribing its social identity in the public arena.” These controls are alive and functioning to a greater extent today. It is my opinion that the only logical way to change how African Americans had been defined in the past was through research.

As I dug deeper, my interests led me to Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921. After two years of research and two trips to the Greenwood Section of the city, better known as Black Wall Street, I was determined to craft a novel built around the men and women who erected a self-sustaining community within the city.

The tragedies that Black Americans suffered in the early morning hours on June 1, 1921, will never surpass the accomplishments of men like J. B. Stradford and O. W. Gurley, business pioneers that went on to become the wealthiest African Americans in Tulsa.

Both were determined to make the capitalist system work for them. Stradford and Gurley, who were born a few years after Emancipation, owned hotels and rental properties. Stradford’s 54-room luxurious facility was considered the finest black-owned hotel in the country and Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois lodged at Gurley’s place two months before the riot.

Mabel Little arrived in Tulsa in 1915 with one dollar and fifty cents to her name. Through hard work, thrift and sheer determination she built “Little Rose Beauty Shop,” bought rental property and assisted her husband in opening the “Little Restaurant.” Mabel was well regarded and respected in Greenwood. So much so, the Mabel Little Heritage House was built post the riots on the very grounds where the businesses were destroyed.

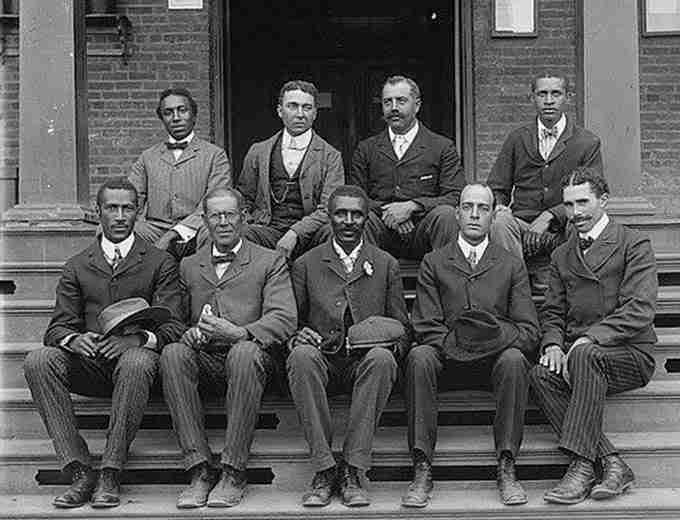

The Greenwood section was a magnet for successful black professionals.

Dr. Andrew Jackson was considered to be the finest black surgeon in the country by The Mayo Clinic; and Andrew Smitherman owned the Tulsa Star, a newspaper that received notoriety because of its fine commentaries written about the plight of black people, not only in Tulsa, but throughout the country.

Historical facts about African Americans must be shared with young black boys and girls who often doubt their ability and opportunity to achieve success in this country. It is imperative that role models much like the men and women of Black Wall Street present themselves now.

Frederick Williams is co-founder of the African American Studies Department at University of Texas at San Antonio and co-founder of Prosperity Publications LLC, a firm that publishes literary works that stress a positive image of the African American culture. Williams is the author of PP’s debut novel “Fires of Greenwood: The Tulsa Riots of 1921.” For more information, please visit: prosperitypublications.com

[/optinlocker]

No Comment