Conclusion from previous edition.

MIAMI (AP) – As their numbers continued to rise, their presence fueled racial and ethnic tensions. Then in the early 1980s, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified Haitians as being among the four risk groups for the new disease. In March 1983, the CDC said the highest number of AIDS cases were among homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroine users and Haitians. They became known as the “Four-H Club.” “In spite of that, you see a sense of soldiering on, you see people working to ensure that they are perceived as human beings, human beings who are worthy of safety, worthy of being valued, worthy of dignity,” Metellus said.

Among their achievements in MiamiDade County: the election of the first Haitian American, Philippe Derose, to public office in 1993 when he became a councilman in the Village of El Portal, and the first mayor in the U.S. in 2000 when he headed the village. A year later, Haitians made history again when they elected Josaphat “Joe” Celestin as the mayor of North Miami, the first Haitian American to become mayor of a sizable U.S. city. That same year, Fred Seraphin became the first Haitian-American judge in MiamiDade County.

With several Haitians elected to the Florida Legislature, the community would make history again in 2010, when Jean Monestime, who arrived in Miami by boat in 1981 from Haiti, became the first Haitian American to serve on the Miami-Dade County Commission. Twelve years after his election, Monestime, who was term limited, has been replaced by Bastien.

A grassroots activist who once worked at the Haitian Refugee Center under the supervision of attorney Steve Forester – one of the community’s consummate immigration advocates – Bastien arrived here in the early 1980s from Haiti, herself fleeing the Duvalier dictatorship.

“Haitians contribute greatly to build the social, political and economic fabrics of their adopted country,” she said. “Given the same opportunities under the right conditions, they can do the same in their homeland.”

Abel Jean Simon Zephir was 16 when he left Haiti on Aug. 15, 1973, and landed in South Florida with 61 other Haitian refugees. Zephir knew some of the passengers who had arrived with Bernard on the first boat, and thought his entry into the U.S. would end up being much the same: a brief detention then release.

Instead, he spent nine months in detention, the beginning of U.S. immigration detention policy as it exists today.

“Even though some of us told immigration very clearly why we left Haiti, because of political persecution, it didn’t matter,” he said. “Their goal was to throw us in jail.”

Zephir’s boat was the third one to arrive in South Florida loaded with Haitian refugees, and the environment was starting to change for asylum-seeking Haitians. During his imprisonment, he and his fellow refugees were transferred from Florida to Texas.

Then, in the spring of 1974, a young Haitian named Turenne Deville was denied asylum and killed himself inside a Miami jail rather than face being sent back to Haiti.

Zephir said they learned the news from the director of the Texas facility, who gathered him and all of the other Haitians and said, “Bad news… One of you died last night.”

“Turenne Deville killed himself,” Zephir said, breaking down as he recalled the director’s words and attempt at consoling them. “That’s the only time I felt that the detention officer was a human being.”

Zephir and his fellow Haitians were finally released, the result of the activism and legal action by Mompremier and his Haitian Refugee Center, which was then backed by the National Council of Churches. “They put us on a bus,” he said. “I arrived Saturday midday in Miami at the Haitian Refugee Center.” Deville’s death became a turning point in the movement, Zephir said.

“You had a solid Haitian community in New York. you had a lot of Haitian students at Columbia University, you had a community of exiles,” he said. “They felt that (Deville’s death) was not acceptable because they themselves were victims of Duvalier’s regime,” Zephir said.

The Haitians in New York decided that the Haitians in Miami “needed our help,” Zephir said, and between 1973 and 1979, Miami’s Haitian community began getting reinforcements from up north.

Among those supporting the cause was Viter Juste, who rallied Haitians to protest a Miami-Dade School Board policy prohibiting children of undocumented Haitians from enrolling in school; Rulx Jean-Bart, a onetime student organizer at York College who became director of the Haitian Refugee Center, and the late Bernard Fils-Aime. A former student organizer at Columbia University, FilsAime, who died in Miami in 2020 from COVID-19 related illness, became one of the movement’s top strategists and go-to advisers.

The northern transplants also include Jean-Juste, the maverick Catholic priest who died in 2009. Known as Father Gerry, Jean-Juste was a priest in Boston who had visited Miami for two weeks in December 1977 before moving here permanently in 1978.

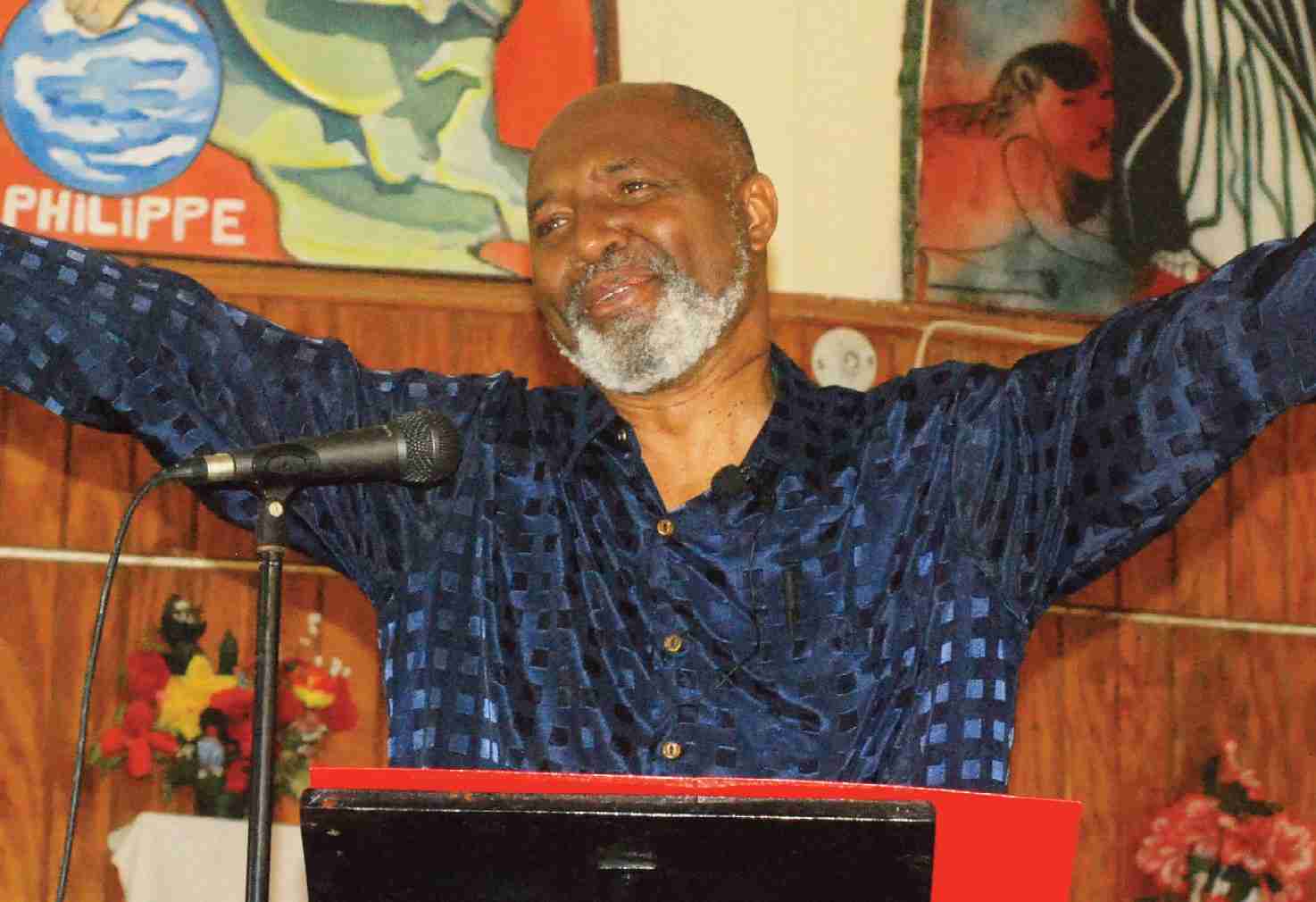

A controversial figure who once picketed the Miami archdiocese and called the archbishop a racist, Jean-Juste was an agitator and Haitian crusader whose presence brought prominence to the Haitian Refugee Center and the Haitian rights movement, as he demanded the release of those detained. His grassroots group, Veye-Yo, could rally Haitians out into the streets at a moment’s notice.

“If it wasn’t for Jean-Juste and his charisma, and ability to organize people, I don’t think that there would be a Haitian community here. It was a combination of a coordinated, legal and political effort, just like what Martin Luther King did,” said attorney Ira Kurzban, who joined the Haitian Refugee Center in the late 1970s as a young lawyer. “Those who say Jean-Juste is the Martin Luther King of the Haitian community, it’s true.”

One of the United States’ foremost immigration lawyers, Kurzban was recruited to work with the Haitian Refugee Center by Gollobin, the Newark-born immigration attorney who, in addition to litigating Bernard’s class action federal lawsuit, litigated other Haitian cases challenging U.S. immigration law.

“When those boats first started to come, the Saint Sauveur, they actually treated the people similar to the way they treated Cubans. It was kind of an open arms policy; they let people in,” Kurzban said. “But as more boats started to come the government realized that they didn’t have a mechanism to treat people in any kind of coordinated and legalistic way.

“The whole forces of the federal government in 1977 and 1978 were against Haitians coming here,” he added. “They were doing everything they could. They put people in removal proceedings, they expedited removal proceedings.” Bernard, who is saddened by her homeland’s ongoing troubles and the fact that Haitian migrants are still being turned away from the U.S., said Jean-Juste doesn’t get enough credit.

“Every day Haitians should raise their hands to the heavens, and light a candle for him and say a prayer for him,” she said.

Zephir, 65, who also credits those early leaders, also pays homage to the Black civil rights movement.

“After 50 years, we can proudly say that the history of the Haitian is a proud one, (it’s) the history of the American people. We are citizens. Like everybody else we have the right, we have the opportunity,” he said, adding, “we have to continue to fight.”

No Comment