WASHINGTON (AP) – Prosecutor Stephen Lanier’s meaning was unmistakable when he urged jurors in north Georgia to sentence the defendant to death in part to deter other people “out there in the projects.”

Almost everyone in the public housing apartments near the scene of the killing of a 79-year-old woman in Rome, Georgia, was black, as was defendant Timothy Tyrone Foster. And after Lanier got through picking a jury of Foster’s peers, all the jurors were white. So was the victim.

Foster has been on death row for nearly 30 years, but his case still is making its way through the courts. The actions of Lanier and his staff will be in front of the Supreme Court on Monday, when the justices will consider whether the exclusion of all the black prospective jurors is a form of racial discrimination in violation of Foster’s constitutional rights under a test the high court laid out in 1986.

Georgia courts have consistently rejected Foster’s claims of discrimination, even after his lawyers obtained the prosecution’s notes that revealed prosecutors’ focus on the black people in the jury pool. In one example, a handwritten note headed “Definite No’s” listed six people, of whom five were the remaining black prospective jurors.

The case arrives at the court a few months after Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg said the court should consider declaring the death penalty unconstitutional. Foster’s case highlights several issues in the wider debate over capital punishment, including questions about his mental capabilities and the length of time he has lived under a death sentence.

The only issue before the justices on Monday deals with the way this particular jury was put together. Lanier, who did not respond to requests for an interview, has consistently denied any intent to discriminate, and the state argues in defending his actions that prosecutors actually wanted a black juror to avoid defense accusations that the jury was a “white lynch mob.”

But Stephen Bright, a veteran death penalty lawyer who is representing Foster at the Supreme Court, said evidence of a racial motive is extensive and undeniable.

As senseless killings go, Queen Madge White’s death was as brutal and pointless as they get.

White had the misfortune to use her bathroom in the middle of the night. Only when she returned to her bedroom and turned on the lamp beside her bed did she notice Foster in her living room, according to Foster’s confession to police. Foster said he was just out to rob White’s home, but things got out of hand when she grabbed a knife and chased him around a living room chair.

He picked up a fireplace log and hit White hard enough to break her jaw. Then he sexually molested her with a salad-dressing bottle and strangled her to death.

Foster’s trial lawyers did not so much contest his guilt as try to explain it as a product of a troubled childhood, drug abuse and mental illness. They also raised their objections about the exclusion of African-Americans from the jury. On that point, the judge accepted Lanier’s explanations that factors other than race drove his decisions. The jury convicted Foster and sentenced him to death.

The jury issue was revived 19 years later, in 2006, when the state turned over the prosecution’s notes in response to a request under Georgia’s Open Records Act.

The name of each potential black juror was highlighted on four different copies of the jury list and the word “black” was circled next to the race question on questionnaires for the black prospective jurors. Three of the prospective black jurors were identified in notes as “B(hash)1,” `’B(hash)2,” and “B(hash)3.”

An investigator working for the prosecutors also ranked the black prospective jurors against each other in case “it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors.”

Still, Georgia courts were not persuaded.

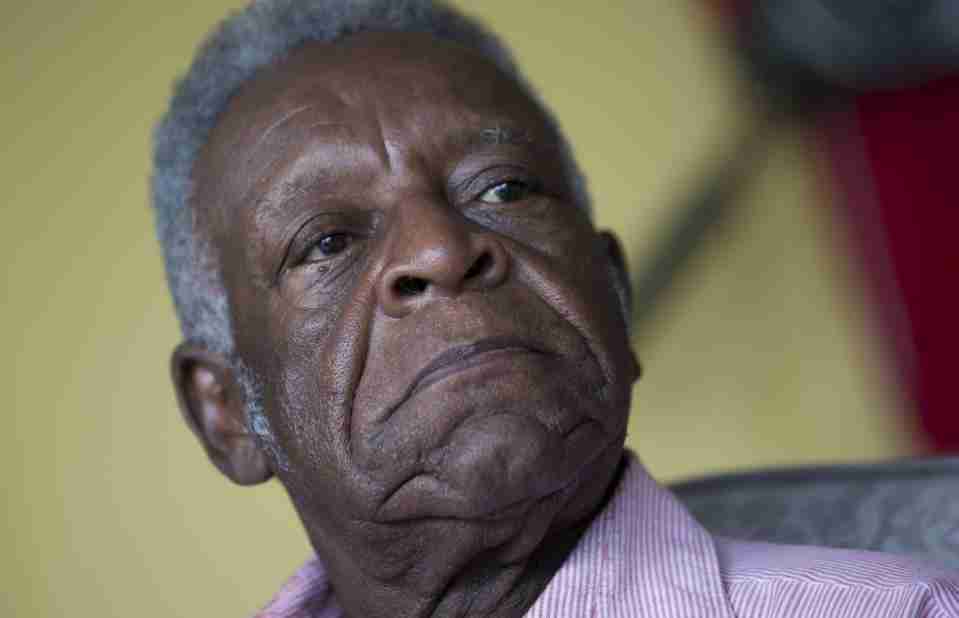

Eddie Hood was “B(hash)1” in the prosecutors’ notes. Now 75, Hood said he hasn’t spent much time thinking about that case, although he said he told his wife he had an inkling race played a role in his dismissal.

He said Lanier had no reason to fear he’d go soft on Foster. “I had no problem with the death penalty,” Hood said at his home in Rome.

But he said he was bothered by Lanier’s comment about the projects when a reporter related it to him. “If I had heard that, it would have created some thoughts I wouldn’t have been comfortable with,” he said.

The Supreme Court tried to stamp out discrimination in the composition of juries in Batson v. Kentucky in 1986. In that case, the court ruled that jurors could not be excused from service because of their race and set up a system by which trial judges could evaluate claims of discrimination and the race-neutral explanations by prosecutors. Foster’s conviction came just a year after the court handed down that decision.

Yet despite the decision, “race discrimination persists in jury selection,” said a group of former prosecutors that includes author Scott Turow and former Deputy Attorney General Larry Thompson, who served in the George W. Bush administration.

“If this court does not find purposeful discrimination on the facts of this case, then it will render Batson meaningless,” the ex-prosecutors wrote in support of Foster.

In the course of selecting a jury, lawyers question potential jurors and first try to weed out people for specific reasons including the inability to impose a death sentence in a capital case or personal relationships with people involved in the case.

Both sides also can excuse a juror merely because of a suspicion that a particular person would vote against their client. Those are called peremptory strikes, and they have been the focus of the complaints about discrimination.

Justice Thurgood Marshall warned in the Batson case that the court’s decision, which he supported, would not cure the problem.

“The decision today will not end the racial discrimination that peremptories inject into the jury selection process. That goal can be accomplished only by eliminating peremptory challenges entirely,” Marshall wrote.

Among the current justices, only Breyer has echoed Marshall’s concerns that discrimination is too hard to prove and allegations of bias are too easy to evade.

Marshall was right, Bright said, “but the fact of the matter is there are not the votes for it on the Supreme Court.”

Instead, Bright suggested restricting each side to three such strikes would allow lawyers to get rid of a very limited number of potential jurors they view as problematic, but prevent a prosecutor from engaging in the sort of strategy Lanier used against Foster.

The case is Foster v. Chatman, 14-8349.

No Comment