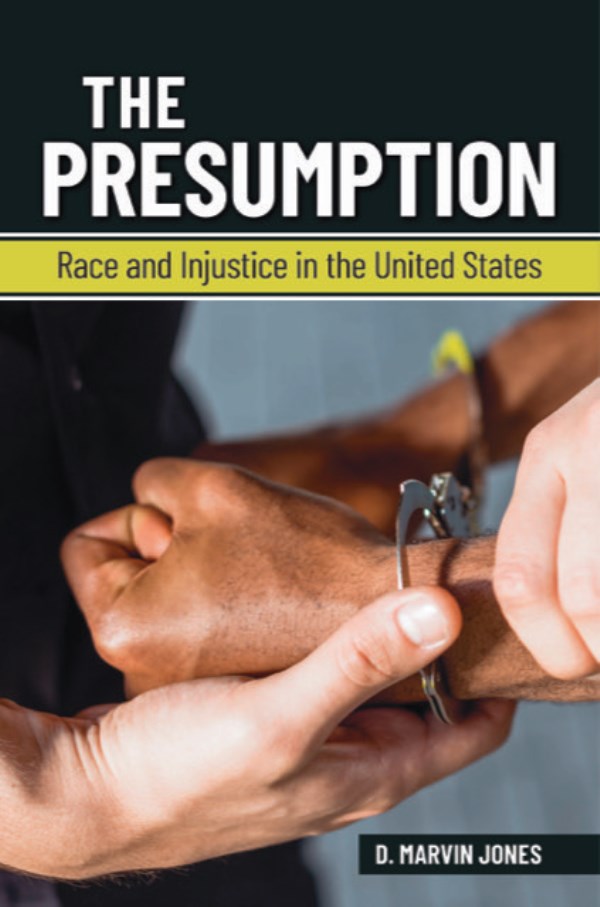

“The Presumption: Racial Injustice in the United States” PHOTO COURTESY OF BLOOMSBURY.COM

In 1982, Ronald Reagan declared a war on drugs. Just three years later, in 1985, the tragic cocaine overdose of promising Black athlete Len Bias shocked the nation. It was unclear if Bias had died from crack, but over the following years, the media flooded our screens with images of “crack addicts “and “crack babies” as symbols of an existential crisis festering in the urban ghetto.

Since then, the so-called War on Drugs has primarily been waged in inner-city areas, causing massive harm

A 1990s Maryland study found that Blacks and whites used cocaine at statistically identical rates. Yet while Blacks made up only 28 percent of the population of Maryland Blacks nonetheless they constituted 68% of those arrested for using cocaine and 90 percent of those incarcerated. We see similar disparities in New York’s war on guns and the stop and frisk campaign that followed. Blacks were 11 times more likely than their white counterparts to be stopped and frisked. These incredible disparities reflect the reality that Blacks, especially in so called high crime areas, are presumed guilty.

But why? For very long time I studied both case law and history to understand why. The result of this journey over many years is my latest book “The Presumption: Racial Injustice in the United States” (Bloomsbury 2024) The “presumption” I speak of originates in slavery. Slavery was a regime of absolute domination. As Orlando Patterson tells us, “Blacks had no honor, no power and no rights.” But how could the peculiar institution of slavery be justified in a Christian society and one founded on the notion that all men are created equal?

This was rationalized in slave society by the notion that Blacks were subhuman, or somewhere on lower rung of the ladder of creation. This same vile and false narrative was reflected in an 1857 decision of Dred Scott. Justice Taney wrote:

“They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far, inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; … It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing, or supposed to be open to dispute.”

What Taney called an axiom I call a presumption. The same presumption used to rationalize slavery was also used in rationalizing Jim Crow laws which followed.

This presumption was on display in the case of Ossian Sweet. Sweet was a Black doctor who tried to buy a house in an all-white neighborhood in the Detroit of the 1920s. On Sept. 8, 1925, Sweet moved into his home, a yellow brick bungalow, on Detroit’s east side. On Sept. 9 a crowd estimated at 500 to 800 people surrounded Sweet’s new home and began to riot: hurling stones, lumps of coal and threats. Someone fired shots into the crowd killing one white man and wounding another. Sweet and 10 other members of his family were charged with murder. Eventually they were acquitted but as Clarence Darrow stated, “had this been a white crowd defending their homes no one would have been arrested. My clients are here charged with murder, but they are here because they are Black.”

The mentality faced by Ossian Sweet did not die with Jim Crow. It is alive and well in the inner city. Evan Howard confronted the same presumption when he came home from college to visit his inner-city neighborhood in West Baltimore.

He walked to the store with an old friend who police identified as gang banger. Howard spends 48 hours in jail for disorderly conduct. One commentator said Howard was arrested for walking while Black and poor in his own neighborhood. The Baltimore police later faced a lawsuit accusing them of systemically arresting Blacks in the inner city without probable cause. The City of Baltimore did not contest the lawsuit.

Cases like that of Dr. Sweet and Evan Howard can be explained only by race, and more specifically by a mindset that conflates Blacks and crime. This mentality has not merely survived into the 21st century, it is deeply implicated in the disparities we continue to see in the drug war, in the rate of Blacks killed by police, by the fact that one in five Black men born in 2001 are likely to experience incarceration in their lifetime.

As Black people we inhabit a paradox. The same country that produced the Declaration of Independence produced slavery. The same country that gave us a Black president gave us the drug war, mass incarceration and the cases we have just described.

The book explores how these injustices are deeply rooted in a set of narratives that were used to justify slavery. Those narratives have crystallized as a pervasive presumption of guilt. Even though we made great progress, those same narratives continue to haunt us like ghosts from our racial past.

Donald Jones is Professor of Law at the University of Miami School of Law. His latest book, “The Presumption: Racial Injustice in the United States,” is available on Amazon.

No Comment