Lakeland, Fla. (AP) – More than 50 years ago, Polk County had thriving Black communities such as Moorehead and Pughsville. Communities were formed as Blacks migrated for work. They were filled with doctor’s offices, grocery stores, and juke joints.

“The communities where Blacks live had their own identity,” Moorhead historian LaFrancine Burton said.

Then came desegregation, commercialization, and eminent domain causing the end to many of these communities.

Families lost their homes and land that they inherited and planned to pass down to generations after them. A financial gain for the cities became a financial burden for the members of the Black communities.

Today The Ledger looks at the rise and fall of a few historically black communities in Polk County.

MEDULLA

Medulla is located south of Lakeland and was developed with the construction of a depot by the Winston and Bone Valley Railroad in 1892. Medulla Phosphate Company was formed in October 1907 by C.G. Memminger. Two months later, he changed the name to Christina after his daughter.

In 1908, Black living quarters were developed so people could work in the community.

According to Pat Taylor, director of the Medulla Resource Center, families came from Georgia, Eaton Park, and Madison, Florida.

According to the Polk County History Center, the onset of World War I in 1914 and the outbreak of Spanish Influenza in 1918 caused a decrease in phosphate production. Although Medulla began to prosper again at the end of World War I, the communities could not survive the effects of the 1925 land bust and the 1929 stock market crash.

Pastor Alex Harper Sr. pastored in Medulla from 1962 to1968 at Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church.

Mount Olive is one of the two main churches in Medulla. The other being St. John Primitive Baptist Church.

“In areas like Medulla, the church was the mainstay that kept people together. The church played a dominant role in keeping people together.” Harper said Medulla was filled with people who moved to work for the local mine and railroad.

“Back then, it was a family-type community. Everybody knew each other,” Harper said.

As the mine and railroad industries changed, Medulla started to see a decline in population.

“The senior members passed away and the younger people left,” Harper said. “It caused a community to die out.”

MOOREHEAD AND TEASPOON HILL

The Moorehead community west of downtown Lakeland began in the 1880s when Blacks moved to work on the railroad.

It was named after the Rev. H.R. Moorehead. According to the history center, the reverend was a champion for the fair and equal treatment of Lakeland’s Black citizens until his death in 1926.

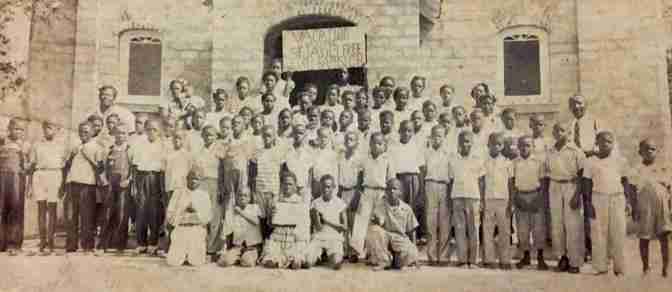

First Baptist Institutional Church was the first Black church in Lakeland. It was established as Saint John Baptist Church in 1884 in Moorehead. The church was also home to Moorehead School. As the school grew, it began to have its own separate building. Both buildings were burned down several times.

“We imagine the Klan did it but there’s no proof of that,” Burton said.

The congregation moved to what is now Martin Luther King Avenue in 1922, and the name changed to First Baptist.

The 35-acre community was annexed by the city of Lakeland and demolished in 1971 through eminent domain in order to build what is now the RP Funding Center.

This uprooted people from their family homes and relocated them to other neighborhoods in Lakeland such as Westlake and Washington Park Apartments.

“The older folks when they were working was very low and the social security that they were getting was minimal,” Burton said. “No one wanted to move because it was a community.”

Many of the elders died within a few years after moving out of Moorehead.

“Everybody was saying that they were heartbroken because they had to move out of Moorehead,” Burton said.

Burton, 73, said moving caused people to have more financial hardships. “Even though they were relocated to better homes than what they had in Moorehead, they ended up with mortgages and they never had a mortgage before. And that was an adjustment for them,” Burton said.

Burton’s mother grew up in Moorehead and her father owned a juke joint called Black & Tan. Burton grew up in Crescent Heights, formerly known as Robinson’s Quarters, on her paternal grandfather’s land that has been in the family for 100 years. She said it would be traumatic for Burton to experience the same situation that the community of Moorehead faced.

“I get all these calls about selling, and I won’t sell it. He worked too hard for it,” said Burton. “I sympathize with the people from Moorehead.” Teaspoon Hill was established North of Memorial Boulevard around 1900. The legend goes that travelers asked if there were other Black neighborhoods in Lakeland and the response from the elders was, “there’s a teaspoon of colored folks living across town on the hill.”

Teaspoon Hill later became known as “The Hill.” Lakeland’s first Black physician, Dr. David J. Simpson, was from Teaspoon Hill. He delivered Florida’s first documented set of quadruplets.

According to the history center, by 1925 public records listed 26 business establishments in the area. The impact of integration in the 1960s caused the end of The Hill.

“We’re losing our history because the older folks who really did stuff during the time of segregation is dying out. It’s up to younger folks to keep the history going,” Burton said.

FLORENCE VILLA AND BOGGY BOTTOM

According to the history center, the north Winter Haven town of Florence Villa began in the early 1880s with the arrival of Dr. Frederick William Inman and his wife, Florence Jewett Inman.

Frederick Inman planted an orange grove and Dan Laramore, a Black Seminole, was his horticulturalist.

In 1886, after a debilitating freeze, the Inmans turned their home into a hotel called Florence Villa. They expanded the building to keep up with the growing number of visitors. They created jobs with the hotel, golf course and the Florence Villa Citrus Growers Association.

The number of Black employees grew, and the area originally known as “The Quarters” became known as Florence Villa.

According to the history center, by 1928 nearly 100 buildings occupied the area north of Lake Silver between Avenues O and W Northwest, 1st Street North, and the railroad tracks. The buildings included churches, a movie theater, a lodge and other businesses.

Pastor Wilford Smith said Boggy Bottom gets grouped together with Florence Villa. However, Boggy Bottom is a separate community that had its own businesses and homes.

Boggy Bottom was established in the 1920s. There were pathways that connected Boggy Bottom and Florence Villa.

“We had ways that if you’re in Florence you knew how to cut through pathways to get to Boggy Bottom. We didn’t have to take the main road,” Smith said.

“Everybody in the area was close, it wasn’t like now with people putting fences up and keeping you from going through their property,” he added.

Smith’s grandmother, Mary Mobley, was a midwife for the community. Smith recalled his grandmother burning “after birth” in her wooden heater.

“She would go and deliver babies in the neighborhood. She had her bag and everything. We used to wonder why it’s 90 degrees outside and she’s getting wood lighting the heater,” Smith said.

Florence Villa and Boggy Bottom started to see a change with the widening of 1st Street. According to Smith, large numbers of homes and businesses along 1st Street were demolished in the late 1970s and early 1980s to make way for the widening project.

“They lost their history, and they did not have anything to pass down to their families or their children,” Smith said. “It was all gone, all the hard work that they put into establishing businesses. When they enlarged the street, they lost most of that.”

PUGHSVILLE

Pughsville is named after Charles Pugh, a Black man who arrived between 1902 and 1903. Pugh was the first pastor of Zion Hill Baptist Church, which was founded in 1908. According to the book “Pughsville: Strength of Four” by historian Patricia Smith-Fields, Pugh was born in Georgia and moved to Winter Haven to be a laborer in the citrus groves. Before it was called Pughsville it was known as “Harris Corner.”

According to the history center, by 1930 Pughsville had more than 100 households and three churches. The history book honors four of the early churches with the title Strength of Four.

“In its hay day we had over 400 residents,” Smith-Fields, 61, said.

“Back then, the adults in the community were your parents. When you misbehaved, they had the right to discipline you,” she added.

According to Smith-Fields, the community had an array of professionals, including educators and service workers. They had juke joints, playgrounds and small businesses. She said they were a spiritual community.

“We had churches all around us. People were parishioners and took value in the spirit of serving the Lord.” A rash of rezoning in the mid-1970s turned Pughsville from residential to commercial.

“It was bittersweet because it was a community where everybody knew everybody,” Smith-Fields said. “You lost that close community network because you had businesses that came in and changed the layout of the community,” she said.

KEEPING HISTORY ALIVE

Each community has ways of remembering its history.

Pughsville began hosting yearly reunions in 1998. The reunion is held during Memorial Day weekend. What started as a fundraiser for the churches in the community has turned into a festival celebrating May Day. May Day commemorates the emancipation of slaves in Florida. “It brings back fond memories because you were able to share with the community outside of Pughsville,” Smith-Fields said.

In 2007, there was a dedication ceremony for two historical markers in Pughsville.

Taylor, 70, hosts heritage storytime at the resource center in Medulla. The elders of the community come to the center and share their personal stories about living and working in Medulla.

“What we do is usually celebrate somebody and something did to make those people feel special because their history is important,” Taylor said.

Taylor said the younger people who leave the area don’t have a reason to come back. Harper said he believes creating jobs for the younger generation will give them a reason.

“People in the community have to work together to provide jobs to the younger generation. They need employment. It’ll keep the community alive,” Harper said.

Polk County schools educator Shandale Terrell said he hopes to see a museum for African American history in Lakeland in the near future.

“We really need to preserve those factors, otherwise we’re going to lose them. Within the city of Lakeland, I’m hoping they’ll preserve the Black history that took place,” Terrell, 47, said. Burton spent time interviewing people and documenting their answers. She has published more than 30 articles in The Ledger to help educate others about Moorehead.

“The best way to preserve is the written history, and it has to be correct. Folks have their memories, and you have to try to document as much as possible,” Burton said. “If they told me something, then I would try something to support whatever they remembered.”

Smith was the first person to have a building named after him in the county while still living. The Wilford Smith Resource Center is on Avenue Y in Winter Haven. Smith hosts different programs, including a Boggy Bottom Reunion that includes the communities of Lake Maude and Florence Villa.

“My main goal is to educate our young people about the history of our community because the new generation is coming in and they don’t know anything. The older people are dying out so there’s no history left.

“I’m the last generation that’s left with history that I try to share with people,” Smith said. “Eventually, we’re going to lose the history if it’s not instilled in our young people every day through their families and loved ones.

“We have to instill in our young people that you can have businesses yourself. Your grandparents worked hard. They weren’t educated, but they took what they had and made something big out of what they had,” he added.

No Comment